Measuring Wealth to Promote Sustainable Development

The Measuring Wealth to Promote Sustainable Development project encourages governments and citizens to move “beyond GDP” as the fundamental measure of societal progress.

What's Wrong with GDP?

Concern is growing around the use of conventional economic indicators to gauge and guide national development, notably GDP. Conventional indicators like GDP lead decision-makers to favour policies with short-term benefits over those focused on long-term sustainability.

For over half a century, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been accepted as the universal measure of economic health and national progress. However, GDP does not reflect many basic components of societal progress. It does not address gender equality, health, education, social inclusion, income distribution or environmental quality. The deficiencies of using GDP as a measure of well-being have been widely shared for decades, yet it has proven challenging to change direction. A recent publication by the UN Secretary-General notes that member states could move beyond GDP by implementing comprehensive wealth measures, following the steps proposed by the World Bank (latest report in 2021) and the UN Environment Programme (latest report in 2023).

The Measuring Wealth to Promote Sustainable Development project aims to encourage governments to move “beyond GDP” as the main measure of societal progress. Wealth is, simply put, the sum total of the assets we own as a society. Wealth is important because it represents the resources we have at hand today to ensure our social and economic activities continue in the future. For this reason, measures of wealth provide an important lens to judge our prospects for future well-being.

Wealth at a Glance

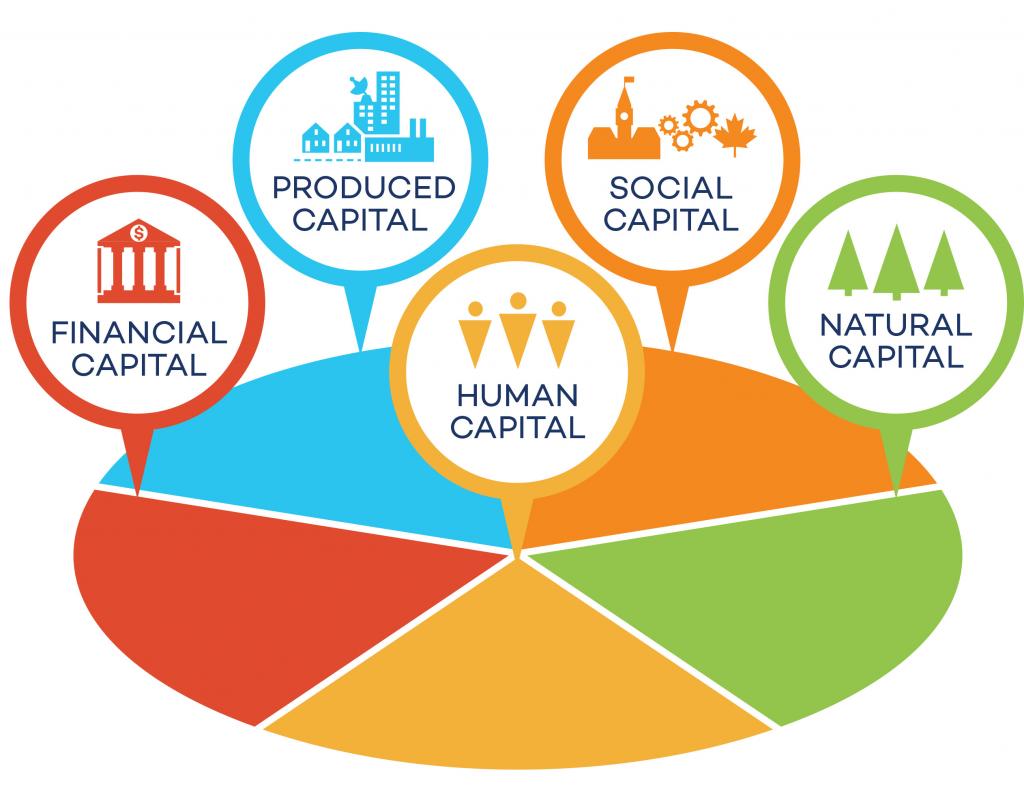

Wealth measures five fundamental types of assets a nation has:

- Produced capital consist of roads, railways, ports, houses, machinery, and the wide variety of other manufactured assets found in the economy.

- Natural capital includes market natural resources such as timber, minerals, oil, and gas. It also includes ecosystems of all kinds; for example, wetlands that help create clean drinking water and forests that act as carbon storehouses.

- Human capital is made up by the collective knowledge, skills, and capabilities of the labour force —the result of lifelong learning in both formal and informal settings.

- Financial capital covers stocks, bonds, and other forms of financial assets. Investments by governments, businesses, and households are often aimed at building up stocks of produced and financial capital.

- Social capital represents the norms and behaviours that define interactions between members of society, including how safe people feel in their communities, inclusivity, and trust in important institutions.

A key question is whether the size of a country’s comprehensive wealth portfolio is growing over time. If it is, then national development is likely sustainable and well-being should be stable or increasing. If it isn’t, development is on an unsustainable path and well-being will decline at some point. This is why measures of comprehensive wealth are increasingly understood to be crucial to assessing societal progress.

Working with Countries to Measure Wealth and Move Beyond GDP

In May 2024, IISD released reports with partners in Ethiopia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Indonesia to expand the push to measure well-being beyond GDP. The findings over the 25-year study period (1995 to 2020) indicate that comprehensive wealth tells a different development story than GDP in all three countries—a story policymakers and citizens need to know if they're to make good policy choices for long term sustainability.

In Ethiopia, IISD partnered with Mesfin Tilahun Gelaye's research team at Mekelle University. Ethiopia’s interest in moving beyond GDP was initially transmitted through its Growth and Transformation Plan II, which focuses on “broad-based growth.” The country also started valuation of its forest as natural capital in 2017. The study in Ethiopia found that despite considerable social, economic, and environmental challenges, Ethiopia has made reasonable progress in expanding its comprehensive wealth. Specifically:

- Comprehensive wealth more than doubled during the study period, growing annually at an average rate of 3.3%

- However, this growth ceased in 2017

- Ethiopia's comprehensive wealth remained very low relative to those of Trinidad and Tobago and Indonesia (In 2020, just 11% and 10% of the two countries’ wealth, respectively)

- Natural capital increased moderately until 2013 before beginning to decline

- Produced capital is concentrated in the manufacturing sector, which accounted for a small share of GDP (4% in 2022). On the other hand, agriculture contributed around 40% of GDP the same year, but only 8% of produced capital was devoted to that industry

- There is a high concentration of human and natural capital in traditional agriculture, which is labour intensive with low returns

In Indonesia, IISD partnered with Alin Halimatussadiah and researchers at the SDG Hub of Universitas Indonesia. The study found that wealth nearly tripled during the 25-year period, growing at an average annual growth rate of 4.3%. However, the relatively slow growth of GDP index (2.8%) over the same time compared with the comprehensive wealth index suggests the Indonesia has not benefited as much from its increasing wealth as it should. Specifically:

- The comprehensive wealth index nearly tripled thanks to changes in human and produced capital, which grew at average annual rates of 4.4% and 5% respectively. However, it then began to decline in 2019.

- Produced capital grew significantly during the study period, though it remains far below industrialized countries on a per capita basis.

- Financial capital dragged overall wealth down, though slightly, as Indonesia is a net debtor.

- In contrast, natural capital hardly changed during the study period. Roughly 36% of Indonesia's market natural capital is made up of fossil fuels, with continued use contradicting Indonesia’s climate goals

- Indonesia is a steward of considerable biodiversity, but is not getting the returns it should when it harvests this biodiversity. Policies to improve rent generation and capture should be considered to generate greater returns and lower the pressure to over exploit its biodiversity.

In the Caribbean, IISD collaborated with Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago. While GDP growth over the 25-year period suggests somewhat sound economic development—with some concerning recent trends—comprehensive wealth paints a picture of moderate progress with a considerable number of red flags. A number of issues are tied to Trinidad and Tobago's economic overreliance on fossil fuels:

- Following the 2008 global financial crisis, the comprehensive wealth index began a steady decline until 2020, falling 3.6% annually. The GDP index fell much less than the comprehensive wealth index during this time, however, sending a less obvious signal of unsustainability.

- Oil and gas is the only market natural asset of real value and its value had fallen to near zero by 2020 due to depletion and falling prices.

- Half of produced capital is tied to the petroleum industry, with a risk of ”stranding” this investment as the world shifts away from fossil fuels.

- Human capital is quite high but falling since the late 2000s. According to World Bank data, Trinidad and Tobago fell from 35th in 2009 to 46th in 2018 in terms of human capital globally.

- There were only limited contributions of financial capital to overall wealth despite the country’s efforts to build up a sovereign wealth fund.

As well as examining changes in comprehensive wealth in each country, the three national reports and synthesis report provide recommendations for national statistical offices, central banks, policymakers and everyday citizens on how to address individual national issues—and give greater prominence to comprehensive wealth overall.

Canadian Comprehensive Wealth

The methodology for building these three national reports was built on earlier IISD studies on Canadian wealth in 2016 and again in 2018. Using data from Statistics Canada from 1980 to 2015, both reports' findings raised a number of red flags for the sustainability of Canadians' prosperity; namely:

- Unprecedented levels of Canadian household debt

- Stagnant human capital (lifetime earning potential) since 1980

- Reliance on foreign lenders for nearly three quarters of investment flows after 2012

- Concentration of business investment in just two areas: housing and oil and gas extraction infrastructure

- An 86 per cent drop in the market value of Canada’s most valuable natural asset: the oil sands

- Vulnerability of Canada’s comprehensive wealth portfolio to climate change impacts

These concerns don't emerge when examining Canada's GDP performance over the same time period, which paints a far rosier picture of the country’s success.

Next Steps: Building Capacity to Move Beyond GDP

The next phase of the project will focus on capacity building for experts, policymakers, and academia to improve their skills and capacities to measure wealth. IISD team members identified important gaps and challenges relevant for low- and middle-income countries to develop the requisite statistical and methodological capacities for comprehensive or inclusive wealth indices.

In addition to the data management and analytical capacities, it will be crucial to identify practical linkages between comprehensive wealth and policymaking so these new wealth measures can be applied in a timely and effective way to relevant policy decisions—such as public investment strategies and prioritization; and assessment of alternative development project proposals.

IISD will provide targeted learning for senior policymakers and experts as well as young professionals, growing networks and similar initiatives elsewhere through sharing of experience and invite interested stakeholders to connect with team members Livia Bizikova and Zakaria Zoundi.

Latest

You might also be interested in

Task Force for a Resilient Recovery

With ideas from Canada and around the world, our Task Force aims for a resilient recovery—one that delivers good jobs, is positive for the environment, and addresses inequality.

AquaHacking Lake Winnipeg

We are challenging young innovators to team up and develop new and innovative solutions to tackle urgent freshwater issues.

Inclusive Monitoring to Leave No One Behind in Canada

Leaving no Canadian behind requires understanding who is being left behind, why they are being left behind, and what their needs are to catch up.

Peg

Peg is a community indicator system that has been developed for Winnipeg by Winnipeggers, led by a community-wide consortium of partners spearheaded by IISD and United Way of Winnipeg.