Can Behavioural Science Help Scale Climate Change Adaptation Solutions?

Applying behavioural science to climate change adaptation solutions might feel resource intensive, but research shows it is likely less costly than an intervention that doesn’t work.

Adapting to the impacts of climate change requires changing behaviour on an individual and a collective level—from how households make a living to how communities manage ecosystems, as well as how governments make investments. So why do we ignore the factors that drive how, when, and why people make decisions as we’re designing and implementing climate change adaptation solutions? IISD and Rare’s new report illustrates how behavioural science can help to question and reframe our assumptions about people’s decision making while supporting us in designing interventions that are grounded in a greater understanding of the psychological, social, and structural drivers of human actions.

The Challenge of Understanding People

Several factors prevent countries from implementing and accelerating climate change adaptation solutions. Lack of financial resources and the uncertainties associated with future climate risks are just two of them. But these aren’t the only barriers. Specifically, the psychological and socio-cultural drivers of behaviour are often left unaddressed.

In other words, we ignore the factors that drive how, when, and why people make decisions and take action when designing and implementing adaptation solutions.

Scientific bodies like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Assessment Report Six (IPCC, 2022), recognize the importance of understanding the behavioural dimensions of climate change adaptation. However, in practice, the psychological and socio-cultural factors that influence the adoption of climate change adaptation solutions are often under-researched or ignored.

This is a major hurdle, considering that adapting to the impacts of climate change requires changing behaviour on both an individual and a collective level—from how households make a living to how communities manage their ecosystems, as well as how governments make investments.

Tackling behaviour directly can feel quite complex. First, various historical, politico-economic, socio-cultural, and psychological factors can shape people’s decision-making processes.

Second, people’s actions are situated within a decision-making system comprised of multiple actors, including governments, development partners, civil society organizations, the private sector, communities, and individuals—all facing unique incentives.

Third, our understanding of how people make decisions is often based on assumptions, which leads to ineffective interventions.

Conscious and unconscious processes—such as habits, emotions, biases, and social influence—impact people’s decisions. This means that even when people understand the relevance of a specific solution and shift their attitudes or intentions toward it, this often is not enough for them to adopt the solution.

Most interventions designed to change behaviour tend to overlook such insights, so applying behavioural science to the design and implementation of climate change adaptation initiatives could help us address past failings and improve the acceptability, effectiveness, and sustainability of solutions.

Aerial view of Naveiveiwali village and Wainibuka river and riverbank.

Case Study on Ecosystem-Based Adaptation in Fiji

To pilot and apply a behavioural science lens to a climate change adaptation solution, we focused on a past ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) project implemented by the Fijian government.

EbA, also called nature-based solutions for adaptation, is an approach for adjusting to the impacts of climate change that focuses on protecting, restoring, and enhancing ecosystem services, all while improving communities’ well-being. The Fijian government is seen as a leader on this topic because it recognizes the need to prioritize EbA in key strategic policy documents.

Between 2019 and 2020, the Fijian government implemented a project that supported communities vulnerable to riverine erosion and flooding by giving them vetiver grass to plant along the riverbanks. Vetiver is a non-invasive species of grass with a fast-growing and deep root system that helps stabilize the soil. It is a robust solution to manage climate uncertainties because of its tolerance to both prolonged drought and waterlogging.

The government deployed a one-off intervention in the villages that did three things: i) they provided free vetiver seedlings through a new vetiver grass nursery at the provincial level; ii) they provided payment for ecosystem services, meaning that each village—through existing community groups—got paid to collectively plant vetiver along the riverbank; and iii) government officials hosted awareness-raising sessions on vetiver planting targeted at men and young people.

However, in 2023, 3 years after the communities had planted the seedlings, there had been no maintenance of the vetiver along the riverbanks in any of the villages.

Our research, therefore, sought to explore the behavioural variables that could have contributed to (or impeded) the adoption of vetiver as an erosion-reducing practice among target communities. We selected three rural Indigenous Fijian communities that benefited from this project and a fourth one that did not receive support as a comparison site.

Six Main Drivers of Adoption

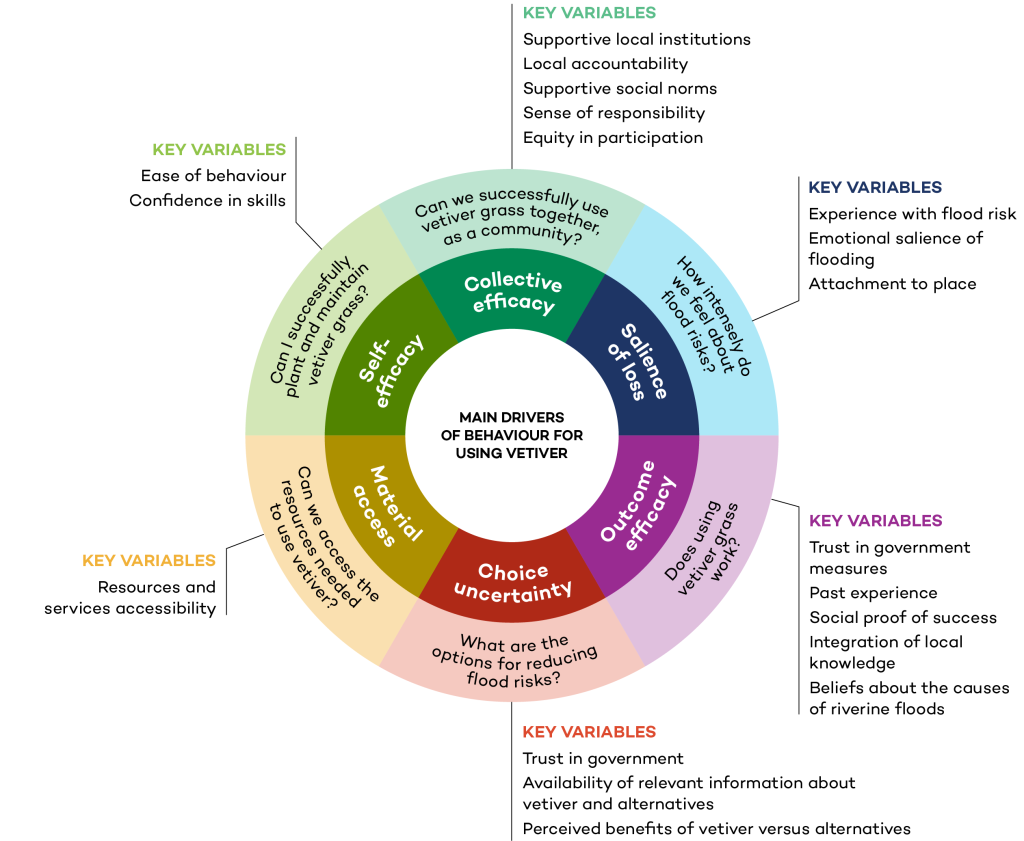

Our research found that the key drivers influencing vetiver grass adoption for riverbank rehabilitation in selected communities in Fiji are complex but identifiable.

Many factors likely influence decision making around vetiver grass adoption at the household and community levels. Our analysis revealed that the six main drivers influencing the adoption (or non-adoption) of vetiver grass for riverbank erosion control against flooding were

-

salience of loss: whether villagers feel strongly about the negative impacts that erosion and flooding have on their lives

-

choice uncertainty: whether villagers are certain about the options available to them to reduce erosion

-

outcome efficacy: whether villagers feel vetiver grass will successfully reduce erosion

-

collective efficacy: whether villagers feel their community can plant and maintain vetiver to reduce erosion

-

self-efficacy: whether villagers feel they personally can successfully plant and maintain vetiver grass to reduce erosion

-

material access: whether villagers feel they can easily access and afford vetiver

We found that together, these drivers worked in concert to push and pull decision-makers toward or away from adopting and maintaining vetiver grass.

Each of these variables was identified from the data and further broken down into its constituent factors. The first two examples listed are salience of loss and choice uncertainty.

Salience of loss refers to the emotional and cognitive responses individuals had toward flood risks and riverbank erosion. When discussing vetiver, several aspects repeatedly surfaced. Participants frequently mentioned experience with flooding and erosion, noting that riverine erosion and flooding seemed to be becoming more frequent and intense. One respondent noted, “The floods have become more often than normal [and] more intense, and the currents are way more swift and bold now that it eats away at our riverbanks every time it floods.”

Another said, "We are very concerned that our village is going to be washed off one day. Flooding is occurring more regularly now as the river has become shallow and wider in some places where erosions have happened. The erosion keeps moving inland; we are concerned that one day it is going to take away houses too."

These comments tied into the emotional salience of flooding, which was also a recurring theme. Participants expressed strong negative emotion related to the impact of riverine erosion and flooding on their lives and those of others.

What was particularly striking was the way participants referred to the loss of land as a direct dilution of their cultural identity. Their attachment to place was obvious, with respondents' cultural identity being closely linked to their land, including the riverbank, heightening their concern about erosion.

One participant said, “[The riverbank] is also a place where we rest and talk about our issues, it’s a bonding place for us women while we’re washing, fishing, or harvesting vegetables,” while another respondent mentioned, “The riverbanks are eroding fast, and we are losing land. Land is an important inheritance culturally as the size of the land depicts the strength of the clan.”

Choice uncertainty involved the perceived lack of clear information about the options available for reducing flood risks. Participants often wondered what other solutions might be available for the community to use. This uncertainty can diminish people’s sense of agency, and respondents felt they lacked information about the choice set available to them and their outcomes. Community members weren’t clear on all the options at hand to help fight erosion or how these options compared to one another—or even to doing nothing. As one participant said, "We want to continue with vetiver but also want to know what other interventions are out there that we can probably choose from."

In scenarios where such decisions could reduce farming land’s immediate potential, combined with our human propensity for preferring known, predictable risks over unknown, ambiguous ones, this uncertainty could be particularly problematic.

The semi-structured interviews revealed that approximately 43% of respondents expressed uncertainty regarding the relative effectiveness of both hard and natural infrastructure. Opinions were evenly split on whether natural infrastructure like vetiver is more effective than hard infrastructure like walls. It was the same with the benefits of vetiver, with only half of respondents (48%) believing that planting vetiver would benefit them personally. Qualitatively, respondents also noted a perceived lack of relevant information on vetiver itself, with comments such as, "[We've received] no trainings/awareness on vetiver grass and its benefits," and "We've heard about it during the community planting program but there was no training or awareness done."

Trust in authorities was another recurring theme, particularly related to how much faith villagers put in key messengers and their information.

For a further breakdown of the other variables, you can read our full report here.

Lessons in Addressing Climate Change Adaptation by Understanding People

This case study illustrates how behavioural science can help to question and reframe our assumptions about people’s decision making and support us in designing interventions that are grounded in a greater understanding of the psychological, social, and structural drivers of human actions.

Behavioural science research shows that a combination of interventions addressing multiple drivers is often required to drive and sustain collective action, and a singular intervention is unlikely to address all variables driving decision making at the household and community levels.

This means that while each of the six drivers is important to support vetiver grass adoption, addressing each variable in a siloed manner will likely not be sufficient to bring sustained change.

In this case, the Fijian government and development partners need to craft interventions that specifically target and address the drivers of vetiver grass adoption identified through research, rather than relying on the assumptions that we all too often fall prey to, for example, that more information will lead to behaviour change. In doing so, they can then test and validate whether those interventions lead to the psychological, social, or structural changes predicted to result in greater adoption (and to identify how a change in a specific driver influences behaviour downstream).

More broadly, expanding the application of behavioural science into the realm of climate change adaptation calls for establishing new partnerships between climate change adaptation experts and behavioural scientists.

Behavioural scientists are already engaging in many fruitful areas of collaboration, such as on financial, public health, and food choice decision making.

Our analysis highlights how important—and urgent—it is for climate change adaptation professionals to also engage with behavioural scientists early, at the start of project formulation rather than in the diagnosis phase, to ensure that initiatives are informed by a deep understanding of human behaviour.

This is alongside real and considered community engagement, which is essential to understanding current behaviour and what it means for enhancing resilience and consideration of the adoption of EbA solutions within the broader context of climate change adaptation and development. In this case, the focus on vetiver adoption at the local level should not overlook the broader and more systemic issues that are causing riverbank erosion, likely driven by unsustainable development such as deforestation, poor road drainage systems, and gravel extraction from the riverbed. Climate change is exacerbating the negative impacts of these factors on communities that are dependent on riverine ecosystems for their livelihoods, and focusing solely on changing behaviour at the household and community levels is not enough to effectively address climate change adaptation.

Finally, applying behavioural science can feel fairly resource intensive, and identifying ways to make this cost-benefit ratio relevant to policy-makers might be necessary if we are to scale climate change adaptation solutions more globally. Understanding current behaviour, and what determines behaviour, often requires collecting and analyzing multiple rounds of primary data at the household and community levels. However, this approach is likely a lot less costly than having an intervention not work, as it’s clear that failure to properly engage with communities in understanding and testing the factors that influence their climate change adaptation behaviour can backfire.

You might also be interested in

Climate Risk Profile—Fiji

This climate risk profile provides an overview of the Fiji's climate context, observed and projected climate change impacts, and a set of recommended NbS for adaptation actions and measures to promote gender-responsive and socially inclusive climate adaptation.

Behavioural Science for Climate Change Adaptation

Applying behavioural science to climate change adaptation solutions may feel resource intensive, but research shows it is likely less costly than an intervention that doesn't work.

Biodiversity Is in Crisis—Here's one way to fix it

A growing movement of projects and partnerships is using locally driven and gender-responsive nature-based solutions to address the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. Scaling up this work to match the urgency and reach of the crises will be a challenge—but it’s one we must embrace.

New initiative harnesses power of nature to build resilience and protect biodiversity

The Climate Adaptation and Protected Areas (CAPA) initiative will use nature-based solutions to support local communities in adapting to climate change while safeguarding critical ecosystems in and around protected areas.