Deaths in Honduras Underline the Grave Risks Facing Indigenous Leaders

Environmental activists and indigenous leaders face deadly risks in many countries, as recent murders in Honduras demonstrate.

Environmental activists and indigenous leaders face deadly risks in many countries, as recent murders in Honduras demonstrate.

The murder of Berta Cáceres in Honduras in March 2016 is another stark reminder that despite signals of progress in advancing sustainable development—from the Paris climate change agreement to the new Sustainable Development Goals—the daily struggles of advocates of environmental protection and indigenous rights too often turn deadly.

Ms. Cáceres was the cofounder of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Movements of Honduras (COPINH) and the 2015 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize. She rallied the indigenous Lenca people of Honduras and successfully pressured China’s Sinohydro and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation to pull out of the planned Agua Zarca Dam. Another member of COPINH, Nelson García, was also murdered in March, and coordinators of the movement have complained of aggressive interrogations following Ms. Cáceres' death.

The Honduras government announced an independent, rigorous investigation into the murders. The world will watch that justice is done. Honduras has become among the most dangerous place on the planet to defend the natural world.

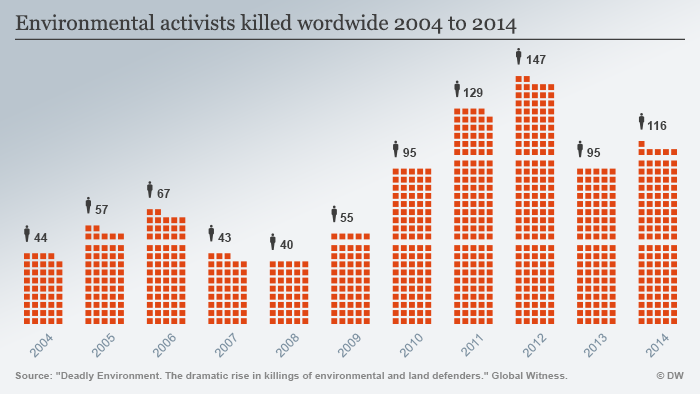

Killings of environmental activists and indigenous leaders has increased sharply between 2002 and 2014, according to Global Witness. At least 116 people were killed in 2014 alone—the most recent data available, with the leading countries being Brazil, Colombia, the Philippines and Honduras. Of these, 47 victims were from indigenous groups. There has been an increase in those opposing hydropower projects, with land disputes being the prime source of violence. More broadly, violence is sparked by those fighting to protect waterways, forests and traditional lands from mining, infrastructure, agriculture and large-scale hydropower projects.

Cases of violence, discrimination and exclusion are higher for indigenous women than for any other group. The United Nations Permanent Forum for Indigenous Peoples reports that violence against indigenous girls and young women is consistently higher than violence facing non-indigenous women and men.

These injustices are largely unreported; indigenous peoples often live in remote areas, cut off from access to public health, education and a justice system that respects collective land rights, and shielded from the scrutiny of the media. Scholar Jeffrey Sisson has warned that indigenous peoples face cultural genocide as well as economic marginalization [1]. One example of this pressure is the relentless disappearance of indigenous languages: according to the UN Secretary General, one indigenous language is lost every two weeks, and of the estimated 6,000 to 7,000 oral languages, the vast majority—around 97 percent—are spoken by small groups of indigenous peoples.

There are signs of progress. In advance of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues meeting in New York in May, positive examples are being pulled together to build momentum to translate the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Rights into a reality that improves the conditions to indigenous peoples. These include Malaysia’s legal recognition of indigenous customary rights to land; the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights ruling that the eviction of the Endorois people from their ancestral lands violated their human rights; Canada’s report of the Truth and Reconciliation; and many other examples from in New Zealand, Greenland, Ecuador and elsewhere.

Despite these advances, too often indigenous women who stand up with remarkable courage against project developers are exposing themselves and their families to violence. The murder of Berta Cáceres is a tragic reminder of how much more needs to be done in the fight for human rights, indigenous people’s rights and justice for women.

[1] Jeffrey Sissons, 2005, First Peoples: Indigenous Cultures and their Futures, Reaktion Books.

You might also be interested in

IISD's Best of 2024: Publications

As 2024 draws to a close, we revisit our most downloaded IISD publications of the year.

Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining of Critical Minerals

This report examines the potential for artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) to take an expanded role in the global supply of critical minerals.

Navigating Global Sustainability Standards in the Mining Sector

This brief examines the latest developments and trends in responsible mining standards and voluntary sustainability initiatives.

Leveraging Digital Infrastructure for Mining Community Resilience

This report explores the socio-economic impacts and potential of new technologies in the mining sector.