The First Earth Day: A founder of the original teach-in remembers

Arthur J. Hanson helped to launch Earth Day in 1970. He reflects on how plans for a "relatively small event" exploded into a global movement.

The original Earth Day took place on April 22, 1970, following on the heels of a teach-in on the environment, hosted by a handful of students and staff at the University of Michigan. Arthur J. Hanson, a former president of IISD, was one of them. Here, he reflects on how plans for a "relatively small event" exploded into a global movement.

I spent five days at the University of Michigan this March, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Teach-in on the Environment that was held there from March 11 to 14, 1970.

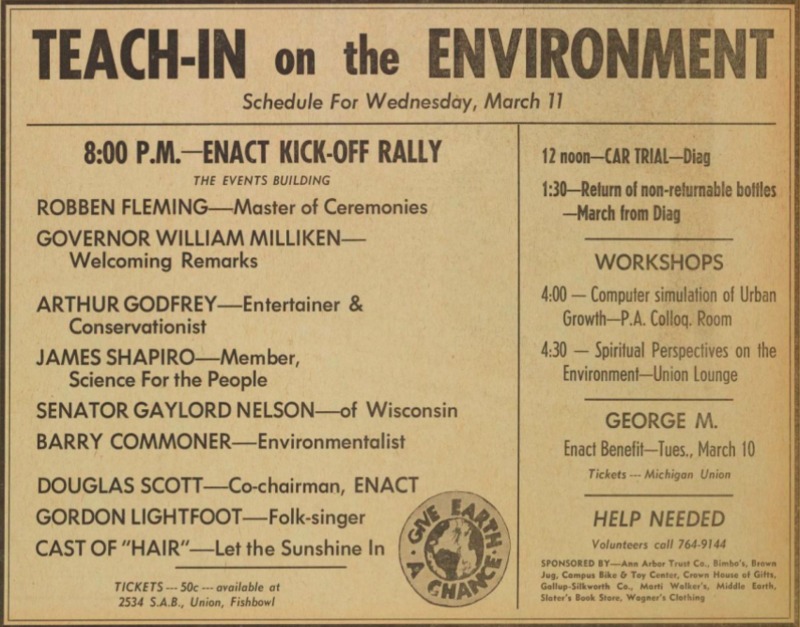

At the time, I was studying for my PhD in ecology. The teach-in concept was cooked up by a small group and led by three of us—at first independently of Senator Gaylord Nelson and his idea of Earth Day, though we ultimately joined forces after a great deal of cross-communication. We mutually agreed that the University of Michigan event in mid-March would be the testing ground for the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970.

We had in mind a relatively small event, perhaps a thousand people. Given the times in the United States, we envisioned patterning it after the recent teach-ins on the Vietnam War.

To our surprise, it became one of the largest events in the history of the university, involving the whole town of Ann Arbor, popular celebrities of the day such as Gordon Lightfoot and the cast of the musical Hair, and some 150 events spread over a week. By some estimates, 50,000 people participated. There were more than 13,000 attendees at the kick-off event, and we had to turn people away.

The inaugural Earth Day: "Four solid days of soul-searching"

Our theme was “Give Earth a Chance,” which saw great publicity across the nation. We attracted to the event all the major TV networks and reporters from all the big papers, including the New York Times, which described the event as “one of the most extra ordinary ‘happenings’ ever to hit the great American heartland: Four solid days of soul‐searching, by thousands of people, young and old, about ecological exigencies confronting the human race.”

Newsweek magazine ran an article with a picture of our button, and we were inundated with orders for buttons from groups across the country planning for Earth Day.

Our event was a huge success and launched subsequent teach-ins and community gatherings on a scale never seen before in the United States or perhaps anywhere.

The triumvirate of leaders included an undergrad student, Doug Scott; a Canadian PhD student, David Allan; and me. Doug and David were co-chairs and I was the finance chair, among other responsibilities (we raised about half a million dollars in today’s value plus untold amounts of in-kind contributions).

Preparations took six months, and we worked with an incredible team of hundreds of volunteers, a steering group of about 13 people—many of whom were from the community of Ann Arbor, including university professors and students—and expertise drawn from sources around the continent. We had the full support of the senior administration, from the U of M president down.

Many stories can be told, but what I discovered personally was the magnitude of what can be accomplished by a small group of people in the right place at the right time. We were riding a wave and, it seemed, could achieve the impossible. This was an experience never to be forgotten and, in some ways, never to be repeated. It helped shape the lives and careers not only of the three of us who started it but also of many others, as we discovered at the 50th anniversary celebration. For me, it changed my career goal from scientist to interpreter of science for new directions in public policy.

Many stories can be told, but what I discovered personally was the magnitude of what can be accomplished by a small group of people in the right place at the right time. We were riding a wave and, it seemed, could achieve the impossible.

We had some funds left over after the event and wanted the teach-in to leave a legacy for the City of Ann Arbor. So we invested these funds to start a non-governmental organization, for which I was one of five people who signed the inception papers and turned over the seed funds. We patterned this organization, The Ecology Center, after one started the year before in Berkeley, California. It took off from ENACT (Environmental Action Now!), the registered student organization we set up for the original teach-in.

Earth Day, ENACT, and The Ecology Center

The Ecology Center was an almost immediate success and became deeply involved in recycling initiatives. Since that time, it has undertaken many good efforts, not only in the city but elsewhere in Michigan and other places. Over the years, the Ecology Center has raised more than USD 200 million and has an annual budget of about USD 8 million. All from a starting investment of only USD 10,000.

In 1970–71, Dave Allan and I co-authored a book with articles by various speakers from the teach-in with the not-very-inspired title Recycle This Book. It is now out of print, but when I look at some of the articles, it seems they could have been written yesterday.

Adam Rome, now at Buffalo University, wrote a very thoughtful book in 2013 called The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-in Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation. It starts with the University of Michigan event and runs through the beginning of the second decade of this century. He paints a picture that suggests a freshness to the U of M event that was hard to replicate later, despite the great success of some subsequent Earth Day events.

Matthew Lassiter, a history professor at the University of Michigan working with his students, university archivists, and others, is keeping alive the 1970 event and asking what has changed since then. He recently helped prepare an article on the U of M teach-in for the Smithsonian Magazine, which includes a half-hour video made at the time in 1970.

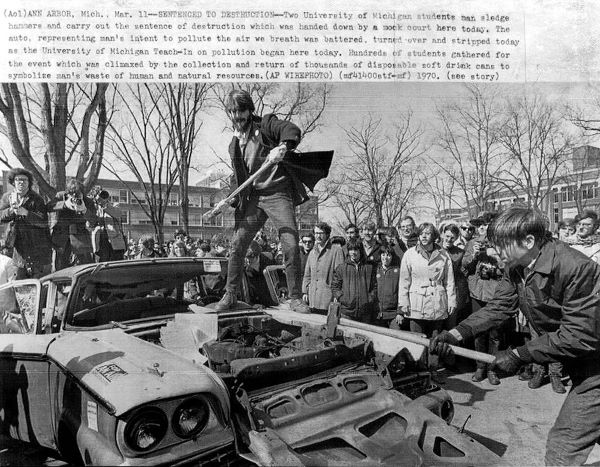

One event that happened during the teach-in that seems to be fascinating for many people is the trial of an automobile, leading to its execution on the University Quad. Brave, considering that, at the time, Detroit was the leading car manufacturer in the world.

We talk about “flattening the curve” to control the pandemic, but it is “bending the curve” for the environment that must happen to bring about harmony between people and nature.

The biggest difference between 1970 and today is our ability to communicate globally about everything. I have celebrated Earth Day in various parts of the world—Indonesia, China, and of course, Canada. Back in 1970, we were thrilled just to have a film crew show up from Japan. At that time, we talked about the Great Lakes dying; now, we talk about global warming, climate change, and the worldwide environmental crisis.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic came along, 2020 was expected to be the Super Year of the Environment. It is urgent that even as we “virtually” celebrate Earth Day 2020, we should make the coming years a Super Decade of the Environment. We talk about “flattening the curve” to control the pandemic, but it is “bending the curve” for the environment that must happen to bring about harmony between people and nature.

National Geographic magazine recently put out a special issue devoted to Earth Day 2070. They made it a flip issue, half devoted to a grim future and half to an optimistic view of what can be expected by Earth Day’s centennial birthday. For the sake of our children and our grandchildren, I hope reality will be the latter.

Speaking of children, it bears mentioning that, six years after the very first Earth Day, our daughter was born—on April 22, 1976. So we now have two excellent reasons to honour that day in our family!

Arthur J. Hanson is an Officer of the Order of Canada and a Distinguished Fellow with IISD following his term as President and CEO from 1991-98. For more information on the origins of Earth Day, see the Environmental Justice HistoryLab site.

You might also be interested in

For Nature-Based Solutions to Be Effective, We Need to Work with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Nature-based solutions have been praised as a promising approach to tackling the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. But some Indigenous Peoples and local communities are questioning the legitimacy of the concept and what it symbolizes. It is time to listen to what they have to say.

Good COP? Bad COP?: Food systems at COP29

The 29th United Nations Climate Conference (COP 29) in Baku failed to build on the notable progress made on food systems at COP 28. However, it wasn't all doom and gloom.

Baku Conference Sets New Collective Climate Finance Goal

The Baku Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC COP 29) delivered what the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) describes as “a milestone agreement that will inform climate action for years to come.” Countries set a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance. The operationalization of the market-based cooperative implementation of the Paris Agreement (Articles 6.2 and 6.4) was another major outcome. Yet, parties could not reach agreement on a number of issues.

What to Expect at Plastics INC-5

Q and A with Tallash Kantai of Earth Negotiations Bulletin on INC-5.