The Future of Trade and Investment Deals in a Critical Minerals Boom

As global demand for critical minerals surges, trade and investment agreements play a key role in shaping relationships between exporting and importing countries. Here is what is needed to maximize economic benefits, improve mining standards, and build resilient, responsible supply chains.

The energy and digital transitions are driving unprecedented demand for critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Projections indicate that the demand for some key minerals could increase by up to seven times by the end of this decade. It goes without saying that mineral-rich developing economies have a unique opportunity to benefit by engaging in responsible mining and processing practices, but they also face challenges in attracting investment for these projects.

Mineral-rich countries have a unique opportunity to capture more economic benefits from their resources through responsible mining and processing.

While offtake and commercial agreements are the most important in attracting investment, governments also have a role to play. Government-to-government trade and investment agreements are critical in shaping relationships between mineral-exporting and mineral-importing countries. These agreements must balance economic development, environmental sustainability, and supply chain resilience. Historically, trade and investment agreements often prioritized securing the importing country’s access to natural resources and protecting investments over fostering value addition and sustainability in exporting countries. This is changing, but not as fast as it should.

The core challenge: Conflicting objectives

Every trade and investment agreement between resource-exporting and importing countries represents a balance between their different interests. While they share the objective of maximum sustainability to the extent possible, exporting countries aim to maximize domestic value addition and diversify export markets. Importing countries such as the United States, the European Union (EU), and China prioritize affordable and stable access to raw materials, often because they also want to maximize domestic value addition. These opposing goals lead to trade-offs, especially around downstream processing and refining.

Exporting and importing countries both want to maximize domestic value addition, which leads to difficult trade-offs.

Key trends in free trade agreements and investment agreements

Free trade agreements (FTAs) are evolving to include critical mineral-specific provisions. Most of these provisions still focus on securing reliable access to raw minerals for importing countries, but there are exceptions where exporting countries have secured space for policies to promote local value addition. In agreements with the EU, Chile secured protection for its dual pricing systems for lithium, and Indonesia successfully defended policy space for its export controls on key minerals. However, because this protection runs counter to the interests of importing countries, it comes at a price in negotiations. To move beyond this zero-sum approach, governments should see FTAs as a tool to build resilience along the value chain, multiplying locations for sourcing raw materials and value addition.

Investment agreements struggle with legitimacy. The so-called “old-generation” investment agreements unduly protect foreign investors at the expense of policy space for countries hosting foreign investment. Yet they bring few tangible benefits to the host countries. Newer agreements aim to mandate investors to comply with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards and try to better balance investment protection with sustainability, but these provisions often suffer from enforceability issues. Countries like Indonesia and Chile have taken steps to renegotiate or terminate older agreements to prioritize national development.

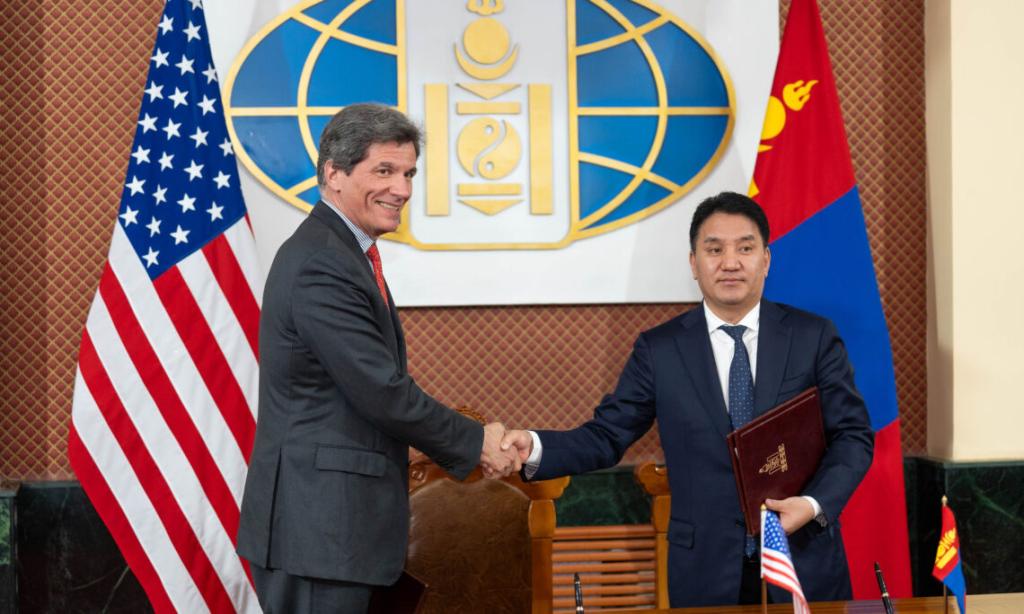

Progress through softer instruments: Memoranda of Understanding

Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) provide a quicker, less formal mechanism for international cooperation on critical minerals. They are negotiated and conducted left, right, and centre. They allow countries to focus on priority issues, but at the same time, they lack the enforceability of trade and investment agreements. As a result, MOUs are only as strong as their implementation frameworks. Unfortunately, many MOUs currently lack the transparency to assess their process, progress, and outcomes. For example, MOUs between the EU and mineral-rich countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo have fostered the exchanges of experts but still fall short of the practical implementation of economic opportunities and ESG standards.

ESG provisions

As consumer demand for responsible minerals rises, one would expect to see more and stronger provisions on mining ESG in FTAs. This is a case of more but not stronger: While ESG considerations are increasingly included in agreements, they are typically phrased in voluntary, non-enforceable language. Embedding robust ESG standards with measurable goals and accountability mechanisms in trade and reformed investment agreements will be crucial to ensure more responsible mining practices eventually.

Recommendations for mineral-exporting countries

To capture more economic benefits and achieve higher mining standards, mineral-rich countries should

- evaluate their mineral policies, offensive and defensive interests, and negotiation leverage before entering into a negotiation;

- use trade agreements strategically, including at a regional level, to maximize opportunities to add value and establish a competitive position within the global value chain;

- reform or terminate old-generation investment agreements that overly constrain their policy space; and

- prioritize enforceable ESG standards to ensure sustainable practices

Recommendations for mineral-importing countries

To ensure resilient and responsible supply chains, importing countries should

- support value addition in mineral-producing countries, including through regional supply chains, to enhance resilience along the supply chains of their imports;

- include enforceable ESG commitments in agreements to align foreign investments with the sustainability goals of both investors and producing countries; and

- support the reform of old-generation investment agreements to deliver fairer and more balanced outcomes for mineral-producing countries.

You might also be interested in

Critical Raw Materials: A production and trade outlook

Background document to inform the Organisation of Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific States (OACPS) Secretariat in developing its critical raw materials strategies.

State of the Sector: Critical energy transition minerals for India

This report presents a comprehensive strategy for securing a reliable supply of critical energy transition materials (CETMs) essential to India's clean energy and low-carbon technology initiatives.

What Makes Minerals and Metals "Critical"?

Exploring how governments define what should be considered as "strategic" or "critical" based on a series of objective criteria.

Financial Benefit-Sharing Issues for Critical Minerals: Challenges and opportunities for producing countries

Exploring nuances in the key features of critical minerals and the new challenges and opportunities they present to fiscal regulation.