What is a limnologist?

A limnologist is essentially a scientist who studies all aspects of a lake, river, stream, or wetland—in other words, an inland body of water.

However, the real definition is much more complex, just like the lakes that limnologists study.

In general, limnologists study the physical, chemical, and biological aspects of a lake and work in a variety of locations such as in a boat on a lake, an office, a chemistry laboratory and more.

Lakes are very diverse, and the research conducted on them can be separated into various subgroups. For example, fish research, toxicology, zooplankton and phytoplankton dynamics, or the chemical and physical composition in a lake. So much information and data can be found within a lake, and it is the job of a variety of scientists with different areas of expertise to research each part.

Furthermore, limnologists’ work involves more than just lake research. It can require communication and outreach with the public, Indigenous communities, shoreline landowners, and developers. Limnologists also collaborate with government and policy-makers, which is essential for turning the research they do into environmental policies and laws to protect the valuable resource of fresh water.

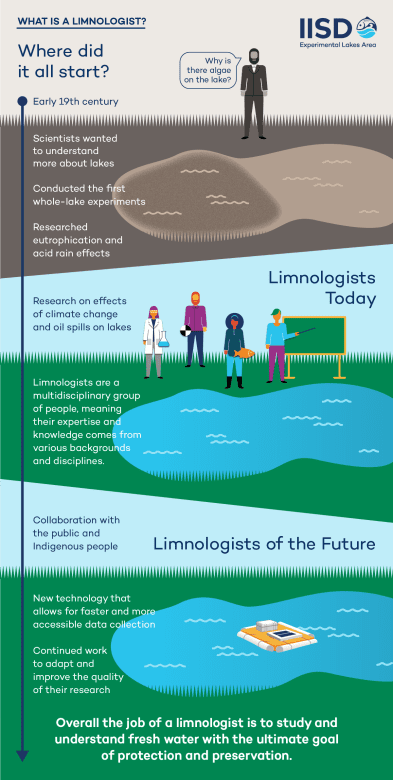

Where Did It All Start?

The study of limnology was first defined in the late 19th century by François-Alphonse Forel and subsequently gained recognition in the scientific community. Historically, lake research was often conducted at a small scale in laboratories; however, this research often failed to include the various environmental conditions and diverse conditions of lakes.

In general, limnologists study the physical, chemical, and biological aspects of a lake and work in a variety of locations such as in a boat on a lake, an office, a chemistry laboratory and more.

This then led to research on whole natural lakes, the importance of these experiments was first recognized by Arthur Hasler. This paved the way for research facilities such as Trout Lake Station operated by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which opened in 1925 and IISD Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) which opened in 1968. This allowed for initial water quality concerns such as eutrophication to be studied at a larger and more dynamic scale—David Schindler was a leading limnologist on this topic. The limnologists of the past were drivers of change and addressed many freshwater concerns head on, conducting lake studies on important topics of the time, such as the effects of acid rain, flooding, mercury, and artificial estrogen.

As I said before, the limnology field is very diverse, thus making it challenging to identify the most influential limnologists. For me, a student in limnology, there a few limnologists that are of interest to me. Colin Reynolds was a leader in freshwater phytoplankton research, which even led him to write a textbook on the topic. Tom Berman made discoveries on phosphorus availability, the role of dissolved organic nitrogen in fresh water, and other research on algal and microbial growth, all mostly on Lake Kinneret in Israel. One of the most influential scientists that contributed significantly to freshwater research is Angelo Secchi, who invented the Secchi disk to determine the clarity of water, an instrument still used today.

Former limnologist Raymond Hesslein began his career at IISD-ELA as a geochemistry graduate student in 1971, initially assisting with research in physical aspects of a lake such as gas exchange. However, over the years, he became involved in research outside his original realm of knowledge that he would have never originally expected. He emphasized that, as a limnologist, it is essential to have knowledge of all areas of lake research due to the connectivity of whole-lake experiments, describing limnology as multidisciplinary.

When I asked him how being a limnologist has changed through his career, he mentioned the advancements in instruments and technology. In the beginning, all lake data was manually written on paper with no computer storage. He said that the data collection now is much more efficient, and that we must be willing to adopt and advance technology to further lake research. However, there are some things that have not changed, such as being out on a boat or using curtains for lake enclosures.

Limnologists Today

Moving into the present, limnologists have continued along a variety of research streams, resulting in the collaborated effort of many different types of scientists, uniquely bringing together the disciplines of chemistry, biology, toxicology, ecology, hydrology, and others.

In an ever-changing world, climate change stands at the forefront of most discussions and concerns. At IISD-ELA, we now have a greater understanding of our lakes thanks to our 50+-year database. We are now looking at this data over a long-term scale to determine how our lake ecosystems react to climate change. Human impacts are the main cause of changes to lakes, which means that limnologists need to continue new and relevant research to monitor or reduce these impacts. This includes research such as the effects of oil spills on lakes and remediation, floating wetlands, and microplastics.

One of the first freshwater microplastic research projects was conducted on the Great Lakes. They found the presence of microplastic pollution in almost all trawl samples collected, with the greatest abundance in Lake Erie. More research has been (and continues to be) conducted on the abundance of microplastics in other lakes, the source of these microplastics, and their impacts on aquatic life.

Another group of limnologists that need to be recognized are Indigenous women, who have a spiritual connection with water due to its life-giving force. In Canada, they are the original and most important voice in protecting water and recognizing its importance for survival. Due to their historical and ongoing respect and relationship with water, they can provide unique knowledge about water and lakes that further advances the field. Limnologists today must continue to work with Indigenous people and combine Traditional Ecological Knowledge with western science.

The Future of Limnology

Limnologists are an adaptive, diverse, and ever-changing group of people who want to improve the quality and range of their research—all with the ultimate goal of protecting fresh water.

New technology is continually being integrated into research at IISD-ELA in order to simplify and improve the effectiveness of the research. Limnologists are also working with data scientists to convert all the long-term data collected from lakes into understandable and accessible forms for other limnologists or the public. A new, innovative approach we are taking is implementing an AquaHive on Lake 227 which can transmit data on lake temperature, chlorophyll-A, and phycocyanin in real-time to be seen and analyzed instantly and remotely. This allows for timely and trustworthy data to be retained much faster than limnologists have traditionally.

In the future it may be possible for anyone to contribute to lake research, whether that is reporting lake conditions at your cabin onto an app on your phone or taking part in community-based research. When the public is involved in lake research and improving lake health, they then become citizen limnologists (or citizen scientists)—allowing for a wider collection of data to be found across the world.

Current students are the future limnologists who will provide new and exciting ideas on freshwater research. Current IISD-ELA student research assistant Emilie Ferguson is on her third summer with IISD-ELA; however, her initial interest in fresh water began thanks to a bilingual interpreter position she undertook at an outdoor environmental education centre, FortWhyte Alive.

Her interest and passion as an emerging limnologist developed further after completing a limnology course at the University of Manitoba and after her first summer position at IISD-ELA. When I asked her how she thinks being a limnologist will change in the future, Emilie predicts the use of artificial intelligence will become more prevalent in freshwater research. It allows for more frequent and consistent data collection year-round and would also be incredibly useful in remote lake ecosystems. She also mentioned the continued importance of science communication and community engagement into the future. She believes that providing opportunities for students, community members, and the general public to connect, discuss, and learn about the importance of freshwater resources is invaluable.

As the limnologist profession grows more diverse and complex the final goal will continue to be what it has always been—to protect and preserve the vital natural resource of fresh water.

Want to get back to some more basics? Be sure to check out our blog posts What Is a Lake? and What Is Fresh Water?

You know that ground-breaking freshwater research you just read about? Well, that’s actually down to you.

It’s only thanks to our generous donors that the world’s freshwater laboratory—an independent not-for-profit—can continue to do what we do. And that means everything from exploring what happens when cannabis flushes and oil spills into a lake, to how we can reduce mercury in fish and algal blooms in fresh water—all to keep our water clean around the world for generations to come.

We know that these are difficult times, but the knowledge to act on scientific evidence has never been more important. Neither has your support.

If you believe in whole ecosystem science and using it to bring about real change to fresh water around the globe, please support us in any way you are able to.