Photography November 29, 2018

Captured & Processed: Thousands of photographs and hundreds of thousands of fish

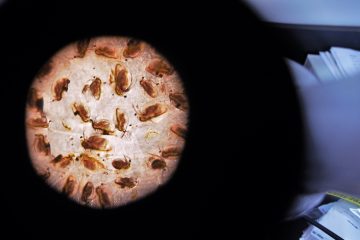

By Lauren Hayhurst, Fisheries Research Biologist

Living, working, and playing in: 1 world-renowned, whole-ecosystem research facility

I’ve exhausted: 2 backpacks, 2 lifejackets, and 2 pairs of fish pants;

Occupied: 3 residences, 3 positions, and 3 perspectives;

Experienced: 4 cooks and many 4-hour shuttle rides;

All in the course of: 5 years at IISD-Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA).

3 Residences & 3 Positions

Growing up spending summers at Lake of the Woods, I figured I had a very good (mildly obnoxious) grasp of freshwater biology concepts and was often informed (warned) by my parents that I could very easily be dropped at the end of the 30-kilometre gravel road to IISD-ELA to have the freshwater scientists set me straight.

Since then I have been supremely lucky and extremely humbled to experience the world’s freshwater laboratory in three Fish Crew capacities: as undergraduate assistant (2014); graduate researcher (2015-17); and biologist (2018). I have fortunately never had to walk into camp.

There were four undergraduate assistants hired in 2014, when IISD had just taken over the facility, and fewer than 20 people at the site. As much as IISD-ELA’s 50-year long-term dataset of whole-ecosystem experiments motivates and inspires, I would argue that meals are our main daily motivator; arriving in Hungry Hall on time for dinner is the greatest driving force at the research station.

Discussions of meals in the middle of a lake in northwestern Ontario occurs as often as discussions of weather in the middle of a city. This commonality reveals the best assessment of the yearly growth of IISD-ELA and the seasonal fluxes in students, researchers and visitors.

Case in point: the entire camp population fit around two tables in 2014. When I returned as a graduate researcher in 2015, the meal seatings grew from two- to four-top. Student positions were created, and field crews hired multiple students (including the rare breed of split-students). With more of an educational-mandated focus, tours poured in and arrivals of external researchers surged. The cooks increasingly accommodated dietary restrictions and preferences, and we experienced a supply-and-demand roller coaster of (initially) bacon and (later) cheese.

A month after my defense in Spring 2018 (and thanks to the even rarer breed of perfectly-timed babies), I accepted a biologist position covering a maternity leave for a year. This past field season was our biggest yet, both in terms of people and projects, and was buoyed by bonus enthusiasm for IISD-ELA’s 50th anniversary!

Right from the start (on a week in May where temperatures jumped to 30+ degrees Celsius and Fish Crew was inundated with thousands of spawning White Sucker and biting black flies), it was apparent that 2018 would break records. There were more than a dozen undergraduate assistants hired in 2018 along with a plethora of graduate researchers.

Our Hungry Hall experience increased to a regular six-top, and swelled on a couple of occasions to the point at which meals were relocated on the beach as we fed (shout-out to cooks, Frank McCann and Jesse Coelho) and accommodated (shout-out to User Services Coordinator Stephen Paterson) 140 people!

3 Positions & 3 Perspectives

I maintain that the position of undergraduate assistant is all sunshine, rainbows, limited internet and bonding over bonfires and canoe trips. Working on Fish Crew, your duties include capturing fish in seines, trap- and gill-nets; recording fish metrics for population estimates; downloading temperature loggers and acoustic fish tracking receivers; assisting with whole-ecosystem experiments; and entering and validating data. Undergraduate assistants are told they have one job: make sure you bring the scale in the field, or you will have a long boat-portage-boat-drive back to camp.

Fish Crew assistants are part of a very seasonally tasked team that is always late for dinner, faithfully pack field lunches on the best Hungry Hall lunch days, and only go on coffee breaks in the summer (we keep morale high with lots of snacks, seat cushions, extensive signage in the Fish Lab, and awful fish puns). As an undergraduate assistant, your IISD-ELA bubble is as big as you make it. You have endless opportunities to study new projects, network with scientists, and participate in outdoor events—the world is your freshwater mussel!

As a graduate researcher at IISD-ELA, you narrow your focus to one whole-ecosystem experiment or question, which is accompanied by more stress and less free time, but also more responsibility. You’re working on per diems, and have to coordinate your coursework to fit around your scheduled, overhauled, and rescheduled fieldwork. You mercilessly recruit people to help you in the field and laboratory (disguised as “Fishing for Science” derbies and mass-minnow-dissection evenings), but with enough good music and better company it becomes a party.

Difficulties in the field are shared by other students who are (literally) in the same boat as you, while later dread-lines in the laboratory and office have you fervently reminiscing about your summer(s) on the lakes. Fortunately, IISD-ELA attracts top scientists who are exceptionally generous with their time and knowledge, and very experienced in putting out (figurative) whole-ecosystem experiment fires, so this two- to five-year commitment (to character-building exercises) provides a whole bunch of exhausted gratification upon completion.

As a Fish Crew biologist at IISD-ELA, your work involves a ton of responsibility but also a ton of satisfaction; you rank comfortably between undergraduate assistants and graduate researchers for amount of stress and free time.

You schedule fieldwork, orchestrate sampling efforts, process fish, instruct students, reinforce health and safety, and report results. You try to create a balance of getting your work done and assisting other projects and crews, as you are compelled to give your time and energy to improving camp life (via capturing and processing thousands of photographs, or creating detailed dioramas and delicious pies—shout-out to biologist Lee Hrenchuk).

You constantly overthink the appearance of your unique workplace to the general public and visiting researchers, and always try to put in the extra effort assisting students with their projects (been there). As a Fish Crew biologist, you are acutely aware of how much capturing and processing one single fish costs in terms of equipment, efforts, and hours; no one, however, prepares you for the compromises, concessions, and bribes you will have to make when your over-zealous undergraduate assistants refuse to stop fishing.

Despite all the variation in levels of responsibility and intensity throughout my IISD-ELA experience, one thing has remained constant to my fish and photograph capturing and processing: an immense appreciation and admiration for Canada’s freshwater systems and the people that study and safeguard them.

Here’s to another 50 years!