The ground shakes as dynamite blasts through the earth of a mining site, creating a channel to redirect water from a nearby lake. The roar of a bulldozer fills the air. It moves along, pushing dirt and rocks to build a dam at the lake’s original outflow. How will the lake downstream respond to reduced water inputs?

A lake trout swims in the middle layer of a boreal lake, its dark green body with yellow spots moving along, looking for food. The year is 2040, and the effects of climate change are becoming more evident, including in this lake. There has been less precipitation, and the lake is getting warmer each year. But what will this mean for this lake trout in search of food?

These two scenarios, both involving a decreased amount of water entering lakes, are exactly what researchers at IISD Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) are currently investigating.

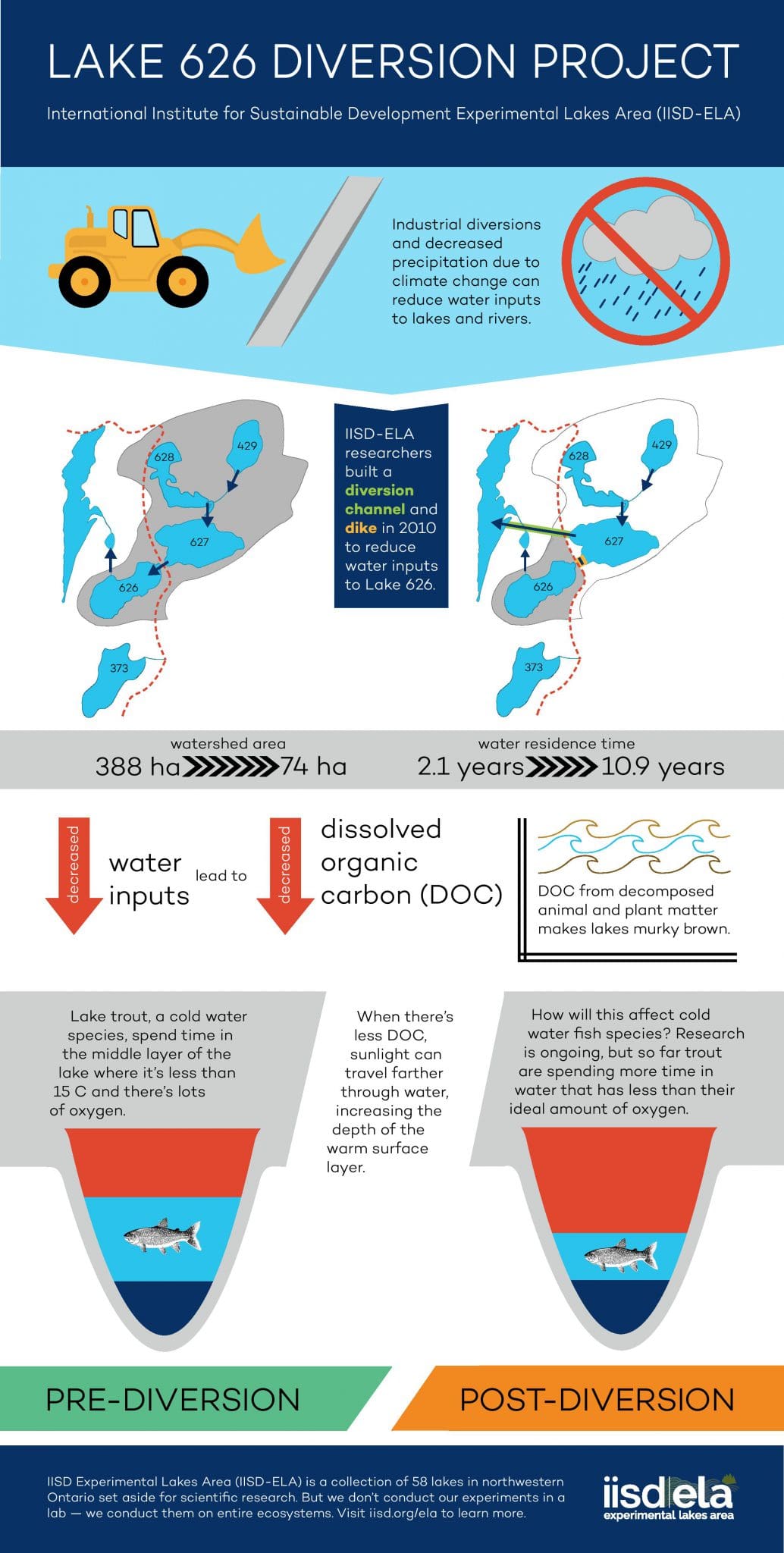

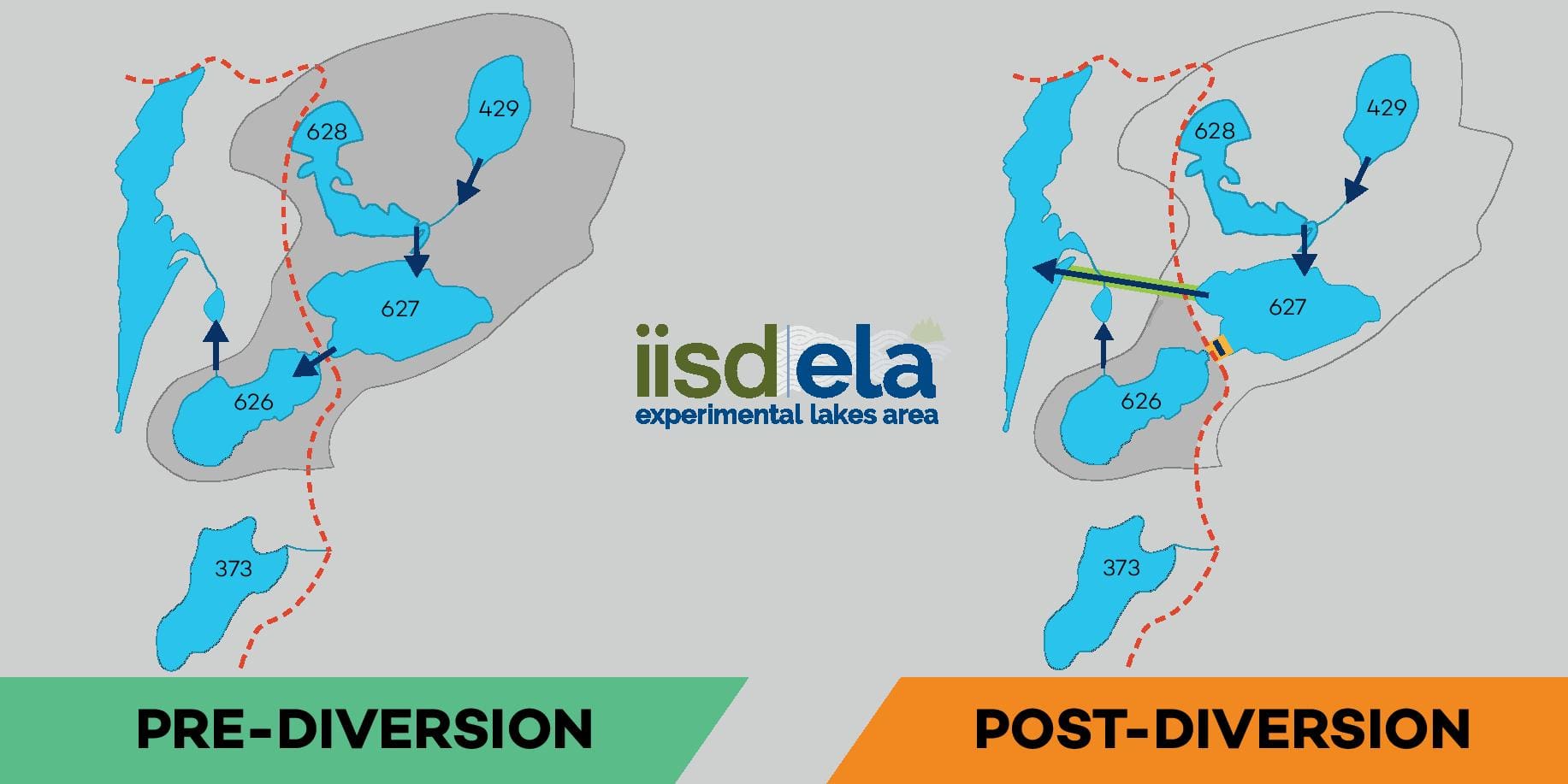

The Lake 626 Diversion Project started in 2008 with scientists from IISD-ELA—or the Experimental Lakes Area, as it was known before 2014—conducting background research on both Lake 626 and a reference lake, Lake 373. Lake 626 was a fourth-order lake (three lakes upstream of it) with a watershed area of 388 ha and water residence time (that is, how long a drop of water stays in the lake) of 2.1 years.

In 2010, the researchers built a 200-metre diversion channel, redirecting water from Lake 627, which is the lake upstream of 626, to a wetland area. They blocked the flow of water from Lake 627 to 626 by building a dike. Lake 626 became a first-order lake (no lakes upstream of it) with a watershed area of 74 ha and water residence time of 10.9 years. The diversion and the dam reduced water inputs to Lake 626 by 80 per cent, mimicking an industrial diversion or decreased precipitation due to climate change.

This part of the experiment itself—reducing how much water enters a lake through redirection—was a first of its kind, says Christopher Spence, a hydrologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada who has been involved with the Lake 626 Diversion Project since the beginning.

“The lake hydrometeorology crowd, we go in and we watch lakes for a few years, and then try to find relationships that way,” Spence says. “But we don’t do experimental manipulations.”

Until now, that is.

Creating the Channel

Ken Beaty started working at IISD-ELA in 1969. Though he has been retired for six years, “they keep calling me in,” he says with a laugh. But he’s happy to help—the site has been a big part of his life.

“There are some things that I remember that none of these people know,” Beaty says, for example, how certain data were collected.

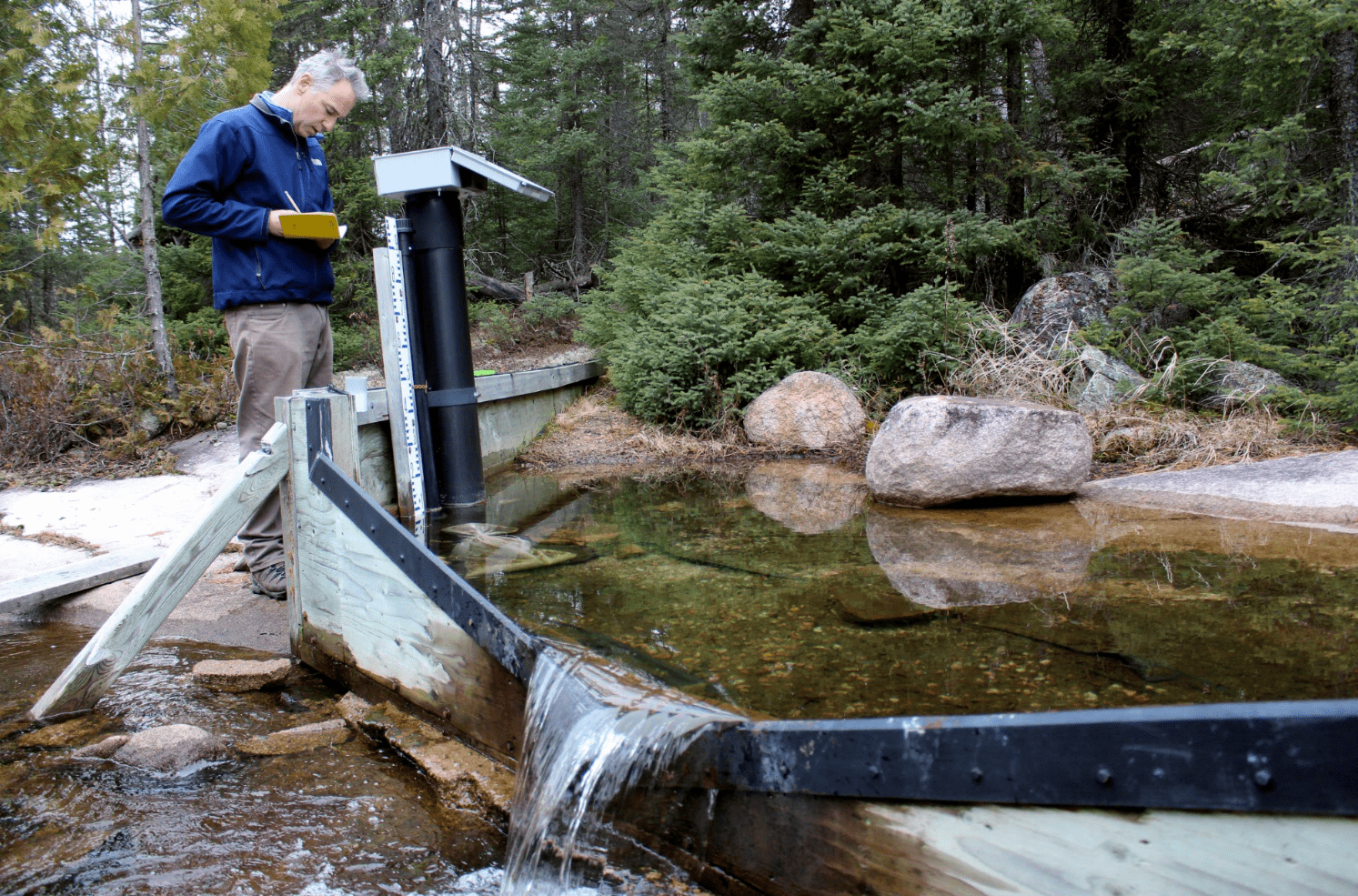

He is a hydrologist and helped identify a suitable lake for the Lake 626 Diversion Project. He had to find a lake that met all the criteria the other researchers needed—the right fish population, water chemistry and so on. He consulted maps and air photos, completed land surveys, and ran a general profile of the area. Once he found a suitable site, he designed the diversion channel. Contractors came in to construct it. They cleared the trees, scraped the dirt and used dynamite to blast through the bedrock. It took about two weeks to complete.

Though this was the first time Beaty had designed a diversion channel, he has altered lakes and wetlands at IISD-ELA before. He has flooded land. He has lowered a lake by 10 feet using a siphon system. He has pumped water with sulphuric and nitric acid over a wetland to mimic acid rain.

And after each experiment is complete, the researchers at IISD-ELA restore the land. For example, once the Lake 626 Diversion Project is done, they will fill in the channel and plant trees in the area.

Surface Water Layer Extending Deeper

The researchers working on the Lake 626 Diversion Project monitored Lake 626 for a few years and discovered significant changes in the amount of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) found in the lake, light penetration and surface water temperature.

Reducing water inputs evidently reduced the amount of DOC, which comes from decomposed plant and animal material, in a lake. DOC is what makes lakes brown. Sunlight bleaches the DOC, and since minimal additional DOC is coming into the lake, the lake gets clearer. Sunlight travels deeper, which warms the lake.

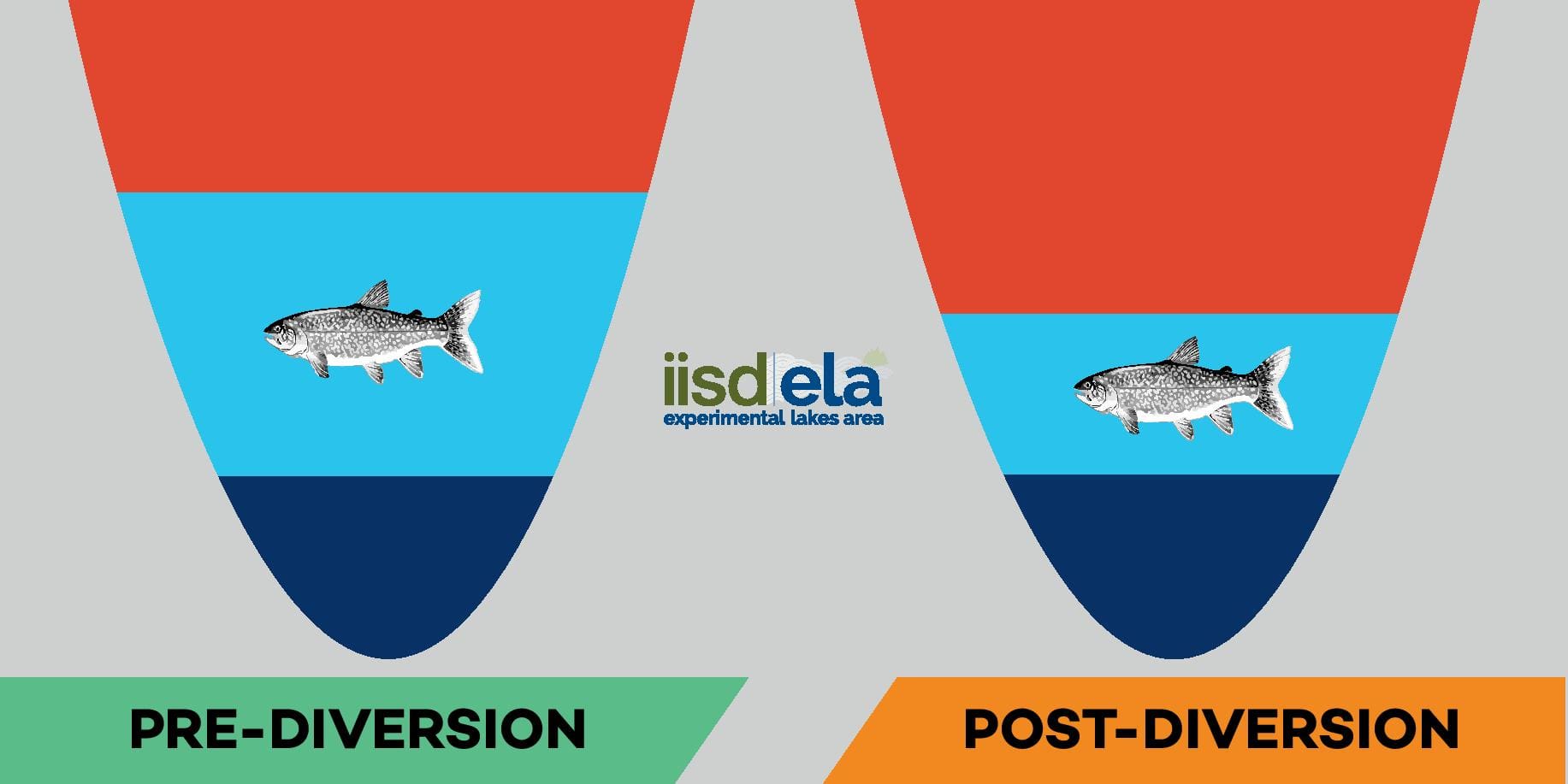

Lake trout, a cold water species, spend their time in the middle layer of a lake. They prefer water high in oxygen that is less than 15°C. The surface layer of the lake is too warm for trout, and the bottom layer doesn’t have enough oxygen.

Since the Lake 626 Diversion Project started, the warm surface layer of Lake 626 is extending deeper, squeezing the lake trout’s habitat. Fish biologists at IISD-ELA are studying how this affects the behaviour of the trout to ultimately understand what drives variations in fish populations among years and among lakes.

“It’s a very basic question,” says Michael Paterson, IISD-ELA’s Senior Research Scientist who has been involved with the diversion project since the start. “People have been looking at that for a long time, but we still don’t have very good answers.”

How Fish Respond

To observe fish behaviour, the biologists implant a tag about the size of a double-A battery into the gut cavity of an adult fish by performing a basic surgery. The tag lasts between 3 and 3.5 years. About 10 to 12 fish are tagged at any given time in both Lake 626 and the reference lake, Lake 373, which are home to up to 350 and up to 300 fish, respectively.

These tags send signals through the water to receivers that record the fish’s depth and spatial position. The researchers can see where the fish spend their time, and how the decreasing habitat size affects them.

The research is ongoing, but there have been some subtle changes in behaviour. For example, lake trout have been spending more time in the water with less than their ideal amount of oxygen.

“It’s still the kind of thing that we’ll have to take a couple years to see if that pattern is consistent or to see how that continues,” says Lee Hrenchuk, a biologist working on the Lake 626 Diversion Project.

Why It Matters

So why should people care about the decreasing size of a coldwater fish’s habitat?

Well, people like fish, and specifically, they like lake trout, as multiple Lake 626 Diversion Project researchers say.

“There will be an impact to fish populations from climate,” says Paul Blanchfield, a former ELA scientist who now works at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. “We can have an idea of not only how sensitive lake trout are to those changes, but also people can really form the basis for understanding how future changes in our climate will impact these lakes.”

Plus there is the industry side of the project and its results, which can help set guidelines and make judgements on industrial projects, like mines and hydroelectric dams.

Monitoring Continues

Last year, all the scientists—biologists, chemists, hydrologists—working on the project met to discuss where the research is at so far. They decided to continue with the study but to sample the lake minimally with more intensive sampling every third year.

After the researchers built the diversion in 2010, the experiment has pretty much run itself, Hrenchuk says. They don’t need any additional infrastructure, so as long as they have the proper permits and monitor the lake, it can be a long-term study.

Like other studies at IISD-ELA, the Lake 626 Diversion Project has many facets—there is research on not only fish behaviour and habitat, but also on fish bioenergetics, zooplankton, aquatic colonization of diversion channels, and whatever else the scientists come up with.

“There are lots of side pieces that come out of the experiment regardless of what the main overarching goal of the original study design was,” Hrenchuk says.

The researchers will continue monitoring the Lake 626 Diversion Project, with the next intensive year of sampling in 2019.

Click here to download this infographic of the Lake 626 Diversion Project.