Comment April 11, 2019

How the U.S. EPA is Changing its Mercury Policy

By Sumeep Bath, Communications Manager, Marina Puzyreva, Policy Analyst

Even before President Trump took office in January 2017, he pledged to jump-start the country’s struggling coal industry and create more jobs. Since he has been in office, it is a promise that’s led to substantial policy changes at the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In what’s seen as another stage in this process, in December 2018 the EPA proposed a revision to the cost–benefit methodology behind its Obama-era regulations on mercury. The EPA now argues that limiting mercury and other toxic emissions from coal- and oil-fired power plants is not cost-effective and should not be considered “appropriate and necessary” under the Clean Air Act.

Mercury poisoning has a wide range of physical and mental symptoms including paralysis, organ damage, even death.

In short, the EPA is reconsidering the importance of co-benefits in its calculations to determine the impact of its mercury regulations on industry and public health. Co-benefits—side benefits that are in addition to the direct benefits resulting from a policy—are traditionally assigned a monetary value and included in EPA policy calculations to justify pollution regulations.

For mercury regulations, the monetized direct benefits of reducing mercury are the increases in I.Q. and lifetime earnings of children born to recreational fishers who consume mercury-laden freshwater fish during pregnancy. The monetized co-benefits include significant health benefits from the reduced emissions of other contaminants not directly regulated by the rule—PM2.5 and sulfur dioxide (SO2). These additional contaminants are reduced due to the installation of required mercury control technology.

When the EPA set up mercury regulations, co-benefits accounted for 90 per cent of the total monetized benefits. Removing them allows the EPA to suggest it is no longer “appropriate and necessary” to regulate mercury emissions since industry costs grossly outweigh the monetized benefits to the public. If this proposal moves forward, it could potentially lead to a loosening of mercury regulations.

What Do the United States’ Mercury Regulations Currently Look Like?

In 2011 the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) were established under the Clean Air Act. It affected new and existing commercial coal- and oil-fired power plants—about 600 across the country. It set standards that were expected to not only dramatically reduce releases of mercury and other hazardous air pollutants into the atmosphere but also releases of nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and particulate matter. Utilities have spent more than USD 18 billion to comply with the requirements.

Even before President Trump took office in January 2017, he pledged to jump-start the country’s struggling coal industry and create more jobs.

MATS has significantly contributed to reducing mercury in the environment and improving public health at a lower cost than anticipated.

The EPA’s Toxic Releases Inventory National Analysis reported that mercury air emissions from electric utilities have fallen by nearly 90 per cent over the past decade. Furthermore, the MATS regulation has been instrumental in fulfilling the country’s requirements under the international Minamata Convention on Mercury.

Why Is Mercury A Problem Anyway?

Mercury is emitted into the environment from many natural and human-made sources. Industrial processes like coal combustion, chemical manufacturing and waste incineration can release mercury as a by-product into the atmosphere (nonpoint source pollution). It can also be released in wastewater from a factory or mine directly into the environment or into bodies of water (point source pollution).

Atmospheric mercury can be transported over long distances before it is deposited on land and water. Once mercury enters bodies of water, bacteria convert it into methylmercury—its toxic form—which is then carried up the food web into top predator species like sport fishes. When people eat those fishes, they also ingest the methylmercury contained in them.

Once the mercury is in our bodies, it is not easily excreted, meaning it accumulates over time causing serious health problems. Mercury poisoning, or Minamata disease (named after the Japanese town in which it was first documented), has a wide range of physical and mental symptoms. These include hair loss, muscle weakness/paralysis, organ damage, loss of senses, depression and even death.

Even so, aquatic systems can recover when mercury stops being added. Just ask the scientists at IISD Experimental Lakes Area, who, in a highly controlled experiment, intentionally added small amounts of traceable mercury to a lake to see how it moved through the ecosystem and food web. Predictably, the amount of mercury found in the fish increased. When they stopped adding mercury, the amount found in fish decreased, suggesting that reducing the amount of mercury that enters the atmosphere may have a significant impact on the amount of methylmercury that ends up in fish (and therefore humans). It should be noted, however, that the response time will vary considerably between lakes.

What Happens Next?

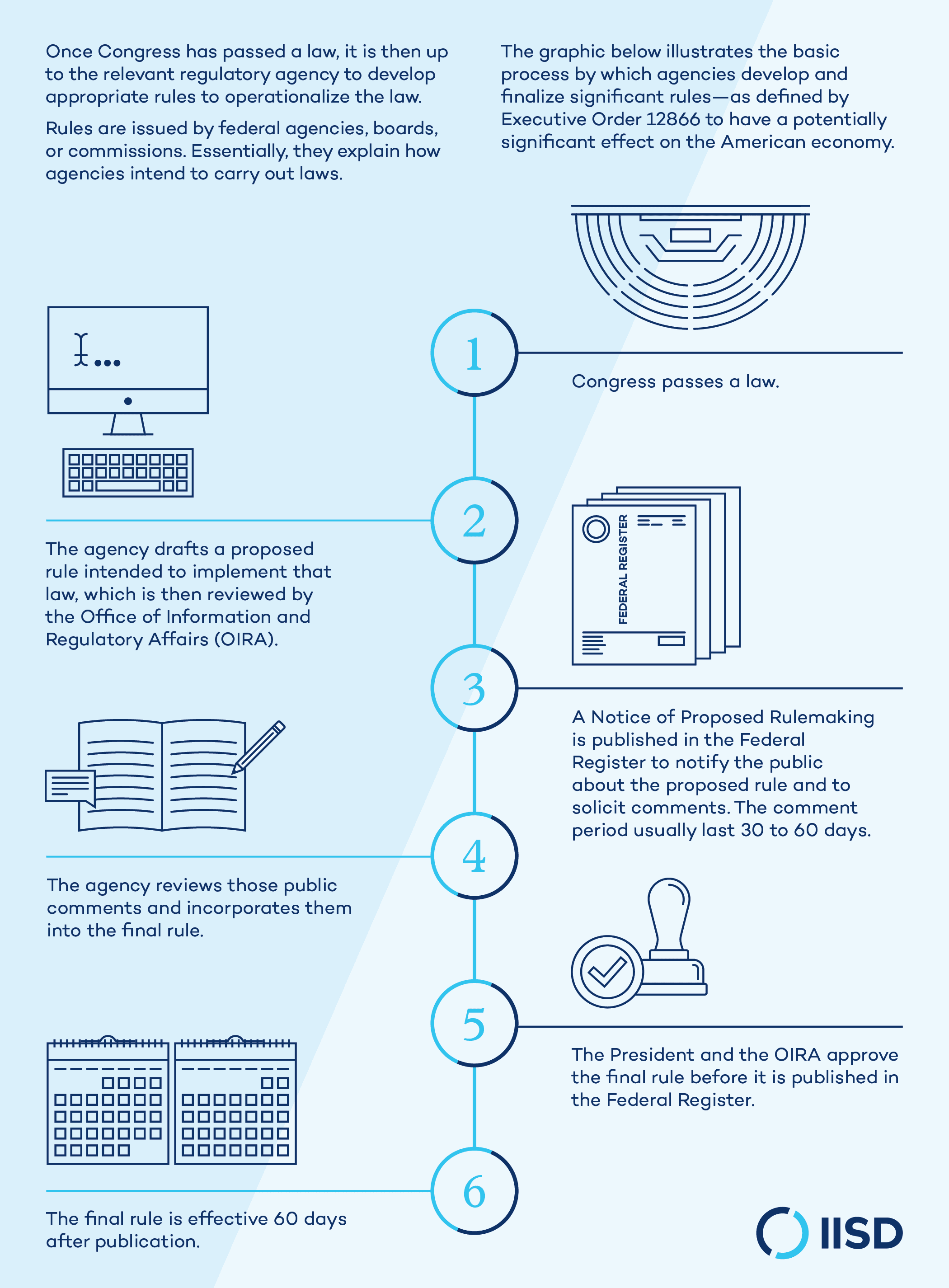

Typically, a rule-making process in the United States must follow an open public process, which includes publishing a statement of rulemaking authority in the Federal Register for all advanced notices, proposed and final rules.

A rule-making process in the United States must follow an open public process.

These proposed changes are currently at the second stage: notifying the public and soliciting comments. The deadline for comments is April 17, 2019. The EPA will also hold a public hearing on March 18, 2019. Before the final rule is published, it will undergo a review by the president and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

Interestingly, some of the greatest criticism of the proposed regulation changes has already come from industry itself. Several umbrella organizations representing hundreds of electric utilities wrote a letter to the EPA in July 2018 asking that the Trump administration to leave the existing standards in place, given the money and time has already been spent to implement the current standards, and given the benefits those regulations have delivered.

What Could This Mean For Canada?

According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, 17 per cent of mercury deposited in Canada (through nonpoint source pollution) comes from the United States.

The impacts of proposed changes for the health of Canadians are uncertain. They will depend on the outcome of the consultation process, the U.S. EPA’s next steps and industry’s response to any mercury regulation changes. However, if new plants are built and mercury emissions do increase, Canada may expect adverse health impacts for populations fishing for subsistence, particularly its First Nations populations.