Awards and Decisions

Unanimous ICSID tribunal dismisses expropriation claim due to Papua New Guinea’s lack of written consent to arbitrate

PNG Sustainable Development Program Ltd. v. Independent State of Papua New Guinea, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/33

Marquita Davis[*]

In an award dated May 5, 2015, a tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) dismissed PNG Sustainable Development Program Ltd.’s (PNGSDP) claim against Papua New Guinea for an alleged unlawful expropriation. It found that Papua New Guinea had not given “consent in writing” to arbitrate claims under the ICSID Convention.

Background and claims

The dispute centered on PNGSDP’s alleged investment in Ok Tedi, an open-pit copper and gold mine located in Papua New Guinea. PNGSDP owned a majority shareholding in the Papua New Guinean company that had a mining lease for the Ok Tedi mine.

In September 2013, Papua New Guinea adopted the Ok Tedi Tenth Supplemental Mining Agreement, which purported to cancel all shares in the Ok Tedi mine owned by PNGSDP and create new shares to be issued to the State. PNGSDP claimed the enactment of the act amounted to an unlawful expropriation without compensation, and initiated arbitration in December 2013, based on two domestic laws of Papua New Guinea: the 1992 Investment Promotion Act (IPA) and the 1992 Investment Disputes Convention Act (IDCA). It also claimed violations of the fair and equitable treatment standard, the guarantee of free transfers, the full protection and security standard, the national treatment standard, among other breaches of the two statutes.

Jurisdiction: did Papua New Guinea “consent in writing” to ICSID arbitration?

The threshold issue of PNGSDP’s claim was whether Papua New Guinea had given “consent in writing” to arbitration, a jurisdictional requirement under Article 25 of the ICSID Convention (para. 44). PNGSDP argued that the requirement was satisfied because IPA Article 39, either on its own or in conjunction with IDCA Article 2, constituted a standing offer by Papua New Guinea to arbitrate investment disputes under ICSID.

The relevant language of IPA Article 39 states: “The Investment Disputes Convention Act 1978, implementing the [ICSID Convention], applies, according to its terms, to disputes arising out of foreign investment” (para. 46). IDCA Article 2 states: “A dispute shall not be referred to the Centre [the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)] unless the dispute is fundamental to the investment itself” (para. 47).

Papua New Guinea argued that neither provision constituted “consent in writing” under national or international law standards: IPA Article 39 merely stated that the IDCA “applied, according to its terms.”

The parties disagreed over what interpretive standard the tribunal should use to examine the disputed provisions.

Papua New Guinea asserted that a literal interpretation of the IPA and IDCA was appropriate under both national and international law and that it required the tribunal to examine the “grammatical and ordinary meaning of the words” (para. 52). Furthermore, it indicated that the tribunal should adopt a restrictive approach, arguing that a state’s written consent to arbitrate must be “clear and unambiguous” (para. 56).

PNGSDP countered that the correct interpretative approach of IPA Article 39 was the one outlined in SPP v. Egypt, which held that jurisdictional instruments should be interpreted “neither restrictively nor expansively, but rather objectively and in good faith” (para. 108). It invoked the effet utile principle of treaty interpretation, which asserts that a text should be read in such a manner that a reason and meaning can be attributed to every word in the text (para. 252). PNGSDP also offered up a “quasi-Vienna” approach, which would allow the tribunal to bring in additional interpretive factors, such as good faith, the object and purpose of Papua New Guinea’s alleged unilateral declaration in its national investment legislation, the circumstances surrounding the declaration, and subsequent state conduct that might indicate its meaning. Again invoking SPP, PNGSDP also asserted that official investment promotion literature, most notably, the statements found on the websites of Papua New Guinea’s Investment Promotion Authority and its Embassy to the United States, should be used to help interpret national investment legislation.

The tribunal sided with PNGSDP and agreed with the SPP decision that jurisdictional instruments should be interpreted objectively and neutrally, rather than expansively or restrictively. It determined that it was well settled that there is no presumption against a finding of jurisdiction under the ICSID Convention, and no greater requirement of proof of an agreement to arbitrate. It concluded that the standard of proof is in most cases “the preponderance of the evidence or a balance of probabilities” (para. 255). The tribunal also “considered the legislative history of th[e] provisions and the investment promotion materials as part of the relevant context in which the legislation was adopted and understood” (para. 274).

According to the tribunal, where domestic legislation has both national and international effects, the legislative provisions are of a “hybrid” nature and, therefore, must be interpreted from a hybrid perspective, taking into account both domestic and international law. Where the two methods conflict, the international law principles will generally prevail, though it is a case-specific determination. The tribunal also agreed with PNGSDP that the effet utile principle of statutory construction was applicable when interpreting “hybrid” provisions. It concluded that, although a state’s interpretation of its own legislation “is unquestionably entitled to considerable weight, it cannot control the Tribunal’s decision as to its own competence” (para. 273).

After examining IDA Article 39, the tribunal concluded that the provision’s “natural and ordinary meaning is a declaration that the terms—all of the terms—of the IDCA apply to foreign investments” (para. 286). As such, Article 39 could not be credibly read to satisfy the specific requirement for written consent to ICSID jurisdiction under Article 25 of the ICSID Convention.

Turning to IDCA Article 2, the tribunal determined that the provision clearly contemplated that future consent was required for submission of claims to ICSID. It then held that there was no other provision in the IDCA that would constitute written consent to ICSID jurisdiction.

To interpret the provisions, the tribunal declined to use the cases provided by the parties, namely Brandes Investment Partners v. Venezuela, CEMEX v. Venezuela, ConocoPhillips v. Venezuela and SPP v. Egypt, because they dealt with different language in dissimilar legislative provisions, and therefore provided no material benefit to interpreting what constituted consent in writing in this case.

Although the tribunal determined that the effet utile principle was applicable to interpreting the provisions, it did not accept PNGSDP’s argument that IDA Article 39 should be interpreted to “trigge[r] the actual application of the ICSID Convention to this dispute” (para. 306). Though the tribunal agreed that meaning should be given to the words of states, and interpretations of treaties that would render particular meanings or provisions redundant or meaningless should be disfavored, it agreed with Papua New Guinea that effet utile did not authorize it to re-write legislative provisions. The party’s intent and good faith are primary, while effet utile “plays a subsidiary role in determining intent” (para. 307). The tribunal distinguished states’ unilateral declarations from cases involving negotiated, bilateral treaties, stating that in some cases a state’s legislation may be “merely confirmatory” (para. 309). Here, the tribunal reasoned that the objective of the IPA was to detail the state’s comprehensive legislative regime addressing foreign investments. For that reason, “recording the continued force and effect of a prior legislative enactment, for the benefit of readers (including investors and courts), serves a useful purpose” (para. 312).

As a result, the tribunal determined that the language of IPA Article 39 even when read together with IDCA Article 2 was insufficient to establish “consent in writing” on behalf of Papua New Guinea to arbitrate claims under ICSID. The tribunal dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction and further declined to consider other jurisdictional objections. Each party was ordered to bear its own litigation costs and split the costs of arbitration.

Notes: The tribunal was composed of Gary Born (President appointed by the Chairman of the Administrative Council, U.S. national); Michael Pryles (claimant’s appointee, Australian national) and Duncan Kerr (respondent’s appointee, Australian national). The award is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4257.pdf.

Government bonds not covered, despite broad definition of “investment” in Slovakia–Greece BIT; tribunal dismisses claims against Greece

Poštová Banka, a.s. and Istrokapital SE v. The Hellenic Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/8

Martin Dietrich Brauch[*]

On April 9, 2015, a tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) dismissed for lack of jurisdiction a case against Greece related to the downgrading of Greek Government Bonds (GGBs) as a result of the economic crisis in the country.

The claimants were Poštová banka, a.s. (Poštová banka), a Slovak bank, and Istrokapital SE (Istrokapital), a company organized under Cypriot law. Poštová banka had acquired a total of €504 million in GGBs through several transactions in 2010; Istrokapital held shares in Poštová banka. The deterioration of Greece’s economy and the downgrading of the GGBs by bond rating agencies led the claimants to initiate arbitration on May 3, 2013 under the Slovakia–Greece and Cyprus–Greece bilateral investment treaties (BITs).

Greece’s jurisdictional objections

Greece objected to the tribunal’s subject matter, personal, and temporal jurisdiction; it also maintained that the claims should be dismissed for abuse of process, and that the tribunal had no jurisdiction over the umbrella clause claims. The tribunal focused first on Greece’s two-fold objections to subject matter jurisdiction, concerning Istrokapital’s claims under the Cyprus–Greece BIT and Poštová banka’s claims under the Slovakia–Greece BIT.

Istrokapital under Cyprus–Greece BIT: “indirect investment” not protected

Istrokapital argued that it had made an indirect investment in GGBs through its shareholding in Poštová banka, and that this investment—and not its shareholding in Poštová banka—was protected under the Cyprus–Greece BIT. Greece objected to the tribunal’s jurisdiction on the grounds that Istrokapital itself did not have an investment under the Cyprus–Greece BIT and could not base jurisdiction on Poštová banka’s GGBs.

The tribunal extensively reviewed case law on whether shareholders have claims or rights in assets of companies in which they hold shares; it looked at HICEE B.V. v. Slovakia, ST-AD GmbH v. Bulgaria, El Paso v. Argentina, BG v. Argentina, Urbaser v. Argentina, CMS v. Argentina, and Paushok v. Mongolia. For the tribunal, these decisions established that, while “a shareholder of a company incorporated in the host State may assert claims based on measures taken against such company’s assets that impair the value of the claimant’s shares,” the shareholder does not have “standing to pursue claims directly over the assets of the local company, as it has no legal right to such assets” (para. 245).

Considering that Istrokapital had sought jurisdiction on its indirect investment, but failed to establish that it had any rights to Poštová banka’s assets protected by the BIT, the tribunal dismissed all of Istrokapital’s claims for lack of jurisdiction.

Poštová banka under Slovakia–Greece BIT: the tribunal structures its approach to interpreting whether GGBs qualified as “investments”

The parties disagreed as to how the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties (VCLT) guides the interpretation of “investment” under the ICSID Convention and the Slovakia–Greece BIT, and as to whether Poštová banka’s GGBs were within the scope of those definitions of “investment.”

The tribunal first analyzed how the GGBs were issued by Greece and acquired by Poštová banka. In particular, it pointed out that Poštová banka acquired its interests in the GGBs not in their initial distribution, but on the secondary market, and that it deposited these interests with Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (Clearstream), a universal depository. It then turned to analyzing whether Poštová banka’s interests in the GGBs qualified as “investments” under Article 1(1) of the Slovakia-Greece BIT.

If “investment” is “every kind of asset,” does the illustrative list serve a purpose?

The claimants understood that their interests were encompassed in the broad definition of “investment” in the chapeau of the Article 1(1) (“[i]nvestment means every kind of asset and in particular, though not exclusively includes: […]”) and in the references to “loans” or “claims to money” in its section (c). They argued that “investment” has no inherent meaning under international law. Greece disagreed, maintaining that the term has an inherent meaning, and that the tribunal should not look for a special definition under the treaty.

The tribunal considered that, while the definition of “investment” under the BIT was broad (“every kind of asset”), this meant neither that all categories qualified as an “investment” nor that the only way to exclude a category would be an express exclusion. It held that “investor–State tribunals are [not] authorized to expand the scope of the investments that the State parties intended to protect merely because the list of protected investments in the treaty is not a closed list” (para. 288).

While observing that several treaties include broad asset-based definitions of “investment,” the list of categories that illustrate what may constitute an investment can vary significantly. To interpret the treaty in good faith—considering its text, context, object, and purpose, as required by the VCLT—the tribunal understood that it should interpret the list of examples under the “investment” definition without making the list useless or meaningless.

The tribunal also looked to case law to support its conclusion. It found that the decisions in Fedax v. Venezuela, Abaclat v. Argentina and Ambiente Ufficio v. Argentina “have consistently considered the text of the list of categories that may constitute an investment as a definitive element to determine whether the activity or operation at stake may be considered an investment” (para. 303).

Are GGBs “investments” under any of the categories of the illustrative list?

The tribunal set out to determine whether Poštová banka’s interests in GGBs fit within the categories of investments listed in the BIT. It started from the premise—undisputed by the parties—that GGBs constitute sovereign debt, which cannot be equated to private debt, as well as securities in the form of bonds, which are subject to specific and strict regulation.

It then noted that none “[n]either Article 1(1) of the Slovakia–Greece BIT nor other provisions of the treaty refer, in any way, to sovereign debt, public titles, public securities, public obligations or the like” (para. 332). The only reference to bonds, under Article 1(1)(b), is limited to bonds issued by private companies (“debentures”). The tribunal agreed with Greece that the exclusion of sovereign bonds from the definition of “investment” indicates that the contracting parties did not intend to cover them as investments.

The claimants had proposed that GGBs fit within a wide interpretation of Article 1(1)(c), which refers to “loans, claims to money or to any performance under contract having a financial value.”

The tribunal disagreed that GGBs could be considered loans, because of the distinction between loans and bonds. Loans generally have identified creditors and limited tradability, are not subject to securities regulations, and involve a contractual relationship between lender and the ultimate debtor. In turn, bonds are generally held by large groups of anonymous creditors, have high tradability, are subject to restrictions and regulations, and involve a contractual relationship between the holder and the intermediaries (not with the ultimate debtor). The facts of the case emphasized the relevance of the distinction: Poštová banka was able to trade the GGBs fast, and had a direct contractual relationship not with Greece, the ultimate debtor, but with Clearstream, the intermediary from which it had acquired GGBs.

The claimants had also wanted to include GGBs within “claims to money” under Article 1(1)(c). The tribunal again disagreed. First, it explained that it should not lightly expand treaty language to interpret a general reference to “claims to money” as including government bonds. Second, looking at the context—“claims to money or to any performance under contract having a financial value”—the tribunal held that any claim to money, to fall within the definition, must arise from a contract with the respondent. This was not the case, given that Poštová banka did not have a contract with Greece.

Dismissal and costs

Concluding that neither of the claimants had an “investment” within the meaning of the relevant BITs, the tribunal dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction, and considered it unnecessary to examine Greece’s other objections.

Even ruling in favour of Greece, the tribunal noted that “the jurisdictional issue was not clear-cut and involved a complex factual and legal background” (para. 377), and ordered each party to bear its own legal costs and an equal share of the arbitration costs.

Notes: The ICSID tribunal was composed of Eduardo Zuleta (President appointed by the Secretary-General of ICSID, Colombian national), John M. Townsend, (claimant’s appointee, U.S. national) and Brigitte Stern (respondent’s appointee, French national). The award is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4238.pdf.

Looking to Venezuela’s Investment Law, majority finds that Venoklim was not a foreign investor and dismisses case against Venezuela; claimant-appointed arbitrator dissents

Venoklim Holding B.V. v. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/22

Martin Dietrich Brauch[*]

The majority of a tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) dismissed an expropriation case against Venezuela on jurisdictional grounds, finding that the investor did not qualify as a foreign national under Venezuela’s Investment Law. The award was rendered on April 3, 2015.

Background and decision to bifurcate

By Decree No. 7712 of 2010, Venezuela ordered the forced acquisition of the assets of five companies owned and controlled by Venoklim Holding B.V. (Venoklim), incorporated in the Netherlands. According to the Decree, the acquisition would be essential for Venezuela’s autonomy in the production of certain lubricants.

Based on Venezuela’s Investment Law and the ICSID Convention, Venoklim initiated arbitration in July 2012 on expropriation claims. It was only in September 2013, when presenting its counter-memorial to Venezuela’s jurisdictional objections, that Venoklim expressly referred to the Venezuela–Netherlands bilateral investment treaty (BIT). The tribunal decided to bifurcate the arbitration, dealing first with Venezuela’s jurisdictional objections and leaving the matters for a later stage.

Venezuela’s denunciation of the ICSID Convention effective after six months

Recalling that it denounced the ICSID Convention on January 24, 2012, Venezuela argued that the tribunal did not have personal jurisdiction. It read ICSID Convention Article 72 to mean that valid consent would only exist if the arbitration request had been received before the notice of denunciation. In response, Venoklim maintained that, under ICSID Convention Article 71, Venezuela’s denunciation would only be effective six months after receipt of the notice of denunciation, and pointed out that the arbitration was initiated before the six months lapsed.

The tribunal rejected the objection, disagreeing with Venezuela’s interpretation of Article 72. According to the tribunal, this interpretation would give Venezuela’s denunciation immediate effect, disregarding the six-month period provided for by Article 71. It would also violate the principle of legal security, to the detriment of investors.

Date when the arbitration request is presented—not registered by ICSID—is the relevant date to establish investor’s consent

Venezuela objected that, when the dispute was registered on August 15, 2012 and the proceeding began, it was no longer a party to the ICSID Convention, even considering the six-month period under Article 71. For Venoklim, however, the registration of the dispute by the ICSID Secretariat is a mere administrative measure, and consent had already been perfected when the request was presented on July 23, 2012. The tribunal sided with Venoklim, concluding that the relevant date for establishing jurisdiction is the date when the investor gives consent by presenting the request, not the date when ICSID registers it.

Venezuela’s Investment Law is not an independent basis for ICSID jurisdiction

Venezuela argued that Article 22 of its Investment Law is not an open and general offer to arbitrate, based on the provision’s ordinary meaning, on political declarations made when the law was enacted, and on comparisons between the provision and offers to arbitrate contained in Venezuelan BITs and in ICSID model clauses. According to Venoklim, the provision implicitly incorporates the BIT and constitutes an independent jurisdictional basis.

After it analyzed the spirit, context and purpose of the provision and the circumstances under which it was drafted, the tribunal concluded that the provision served to confirm Venezuela’s offers to arbitrate made under other legal instruments, such as BITs—but could not be considered an “independent, clear and general” offer to arbitrate (para. 104). Accordingly, it dismissed the objection, in line with earlier ICSID decisions in the Mobil, Cemex, Brandes, Tidewater, OPIC and ConocoPhillips cases.

BIT not an independent jurisdictional basis—but incorporated by indirect reference in Venezuela’s Investment Law

Venezuela claimed that the late invocation of the BIT—not in the request, but later, in the counter-memorial—breached the ICSID Convention and procedural rules, which require that the request must present all the elements necessary to establish jurisdiction.

The tribunal agreed with the investor that there was no late invocation. It reasoned that the counter-memorial merely explained and elaborated on the jurisdictional basis presented in the request—the Investment Law. Article 22 of the Investment Law refers to international arbitration provided for in investment treaties generally. Since Venoklim claimed to be a Dutch investor, the tribunal held that the reference to investment treaties in Venezuela’s law should be read, in this case, as a reference to the Venezuela–Netherlands BIT.

Adopting the effective control criterion under the Investment Law, tribunal finds that Venoklim is not a foreign investor

To demonstrate its foreign nationality, Venoklim invoked the incorporation criterion (referred to in the BIT), but Venezuela argued that the effective control criterion (referred to in the Investment Law) should be used instead. According to Venezuela, the effective control over Venoklim ultimately lay with a Venezuelan company. Therefore, the investor could not be considered foreign nationals under the ICSID Convention, the Investment Law or the BIT.

The majority of the tribunal emphasized that Venoklim needed to fulfill the requirements of Article 22 of the Investment Law to benefit from the BIT, as well as to prove its foreign nationality under the ICSID Convention.

Analyzing Article 22, the majority noted that the provision refers to “ownership” and “control,” but not “incorporation,” as the relevant criteria to determine nationality. Therefore, it held that the investor’s place of incorporation was irrelevant in this determination and, given that the parties had not discussed ownership, it focused on analyzing the control criterion. In this analysis, it found that Venoklim was indeed controlled by a Venezuelan company, which in turn was owned and controlled by Venezuelan nationals.

Finding that Venoklim did not qualify as a foreign investor under Article 22, the majority held that the investor was not entitled to the protections of the provision and, as a consequence, could not benefit from the protections of the BIT either. Accordingly, the majority of the tribunal dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction.

Briefly analyzing the ICSID Convention, the majority reasoned that to look solely at Venoklim’s incorporation in the Netherlands to consider it a foreign investor, even though the investment was ultimately owned by Venezuelans, “would be to allow formalism to prevail over reality and to betray the object and purpose of the ICSID Convention” (para. 156).

According to arbitrator Enrique Gómez Pinzón, the majority was mistaken to analyze the investor’s nationality based on the Investment Law. Given the earlier conclusion that Article 22 could not be considered an “independent, clear and general” offer to arbitrate, but merely confirmed Venezuela’s commitments under investment treaties, he argued that the investor should have been subjected to the nationality requirements of the BIT.

The dissenting arbitrator also disagreed with the majority’s interpretation of the nationality requirements under the ICSID Convention. According to him, the ICSID Convention is silent on a definition of nationality to give the contracting parties leeway to choose a nationality criterion in more specific instruments. In the Venezuela–Netherlands BIT, the two contracting parties chose “incorporation” as the applicable criterion, but the majority disregarded that choice. He also criticized the majority’s decision to pierce Venoklim’s corporate veil without a detailed analysis of whether its incorporation in the Netherlands had been fraudulent or done to evade legal requirements or to harm the shareholders or third parties.

Case dismissed—but Venezuela ordered to cover half of arbitration costs and own legal fees

Even though Venezuela demonstrated that Venoklim was not a foreign investor, leading to a dismissal on jurisdictional grounds, the tribunal reasoned that, since most of Venezuela’s jurisdictional objections were rejected and since Venoklim acted correctly throughout the proceedings, “it would be unfair” (para. 163) for Venoklim to bear all costs. Accordingly, the tribunal ordered Venezuela to bear half of the arbitration costs, including the arbitrators’ fees, and ordered each party to cover its own legal fees and expenses.

Notes: The ICSID tribunal was composed of Yves Derains (President appointed by the Chairman of the Administrative Council, French national), Enrique Gómez Pinzón, (claimant’s appointee, Colombian national) and Rodrigo Oreamuno Blanco (respondent’s appointee, Costa Rican national). The award is available, in Spanish only, at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4229.pdf; the concurring and dissenting opinion, also in Spanish only, at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4230.pdf.

Majority of ICSID tribunal finds no fair and equitable treatment violation by Albania in petroleum dispute

Mamidoil Jetoil Greek Petroleum Products Societe S.A. v. The Republic of Albania, ICSID Case No. ARB/11/24

Matthew Levine[*]

An arbitration between a Greek petroleum products firm and the Republic of Albania has reached the award stage at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The ICSID tribunal found jurisdiction under the 1991 Greece–Albania bilateral investment treaty (BIT).

The tribunal unanimously dismissed the investor’s claim in relation to a purported indirect expropriation. A majority of the tribunal dismissed the investor’s claim that Albania had failed to provide fair and equitable treatment (FET); however, the claimant’s nominated arbitrator found Albania’s conduct to breach the FET standard.

Background

Mamidoil Jetoil Greek Petroleum Products Societe S.A. (Mamidoil) is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of Greece. From 1991 onwards, Mamidoil explored various commercial opportunities in Albania related to its major business activities, namely, the transport, storage and sale of petroleum products.

Mamidoil eventually settled on the construction and operation of an oil tank farm in the Durrës port area (Durrës Tank Farm), which led to a series of increasingly substantial investments in 1999 and 2000. During this period, local government officials sent a series of letters related to Mamidoil’s failure to obtain permits. The Durrës Tank Farm is situated close to a residential area.

The claimant substantially finished the construction of the Durrës Tank Farm by 2000. Subsequently concerns arose regarding the social impact of the tank farm, and the Albanian government embraced, in tandem with the World Bank and the European Union, re-zoning proposals that would relocate Durrës. Albania contended that an eventual ban on fuel vessels at Durrës was part of its long-term transport sector strategy as part of the necessary modernization of its port system.

Mamidoil contended that Albania encouraged it to invest in the country. Albania did not contest that it provided some support to Mamidoil, but contended that this was purely provisional and high level.

Business activities considered as unitary investment for purposes of jurisdiction

Albania had argued that “the composite parts of the investment form a whole and must be considered together” (para. 364). The tribunal agreed that construction of the Durrës Tank Farm, establishment of an Albanian subsidiary that was first controlled and later wholly owned by the claimant, conclusion of a Durrës-related lease by the subsidiary, and operation of Durrës by the subsidiary must be considered as constituting a single investment.

As the tribunal agreed with Albania that the investment be considered as a unity, it was not persuaded by Albania’s argument that certain elements of the investment failed to fulfill the ICSID Convention’s criterion for a covered investment. Rather, it found that the investor’s business activities clearly constituted an investment under the ICSID Convention.

Albania also objected on the basis of illegality, arguing that the investor had failed to obtain required permits. The tribunal found this more relevant to the merits stage: as Albania had informed the investor that it was ready to consider curing the illegalities, it could be expected to accept jurisdiction. (However, the majority subsequently found that without such permits the investor could have no legitimate expectation of proceeding with the investment and that the claim for breach of FET, among other claims, must be rejected.)

Energy Charter Treaty invoked at pleadings stage

In its Request for Arbitration, the claimant based its claim exclusively on the BIT and the ICSID Convention. The claimant’s memorial, however, subsequently asserted that the respondent’s consent to ICSID arbitration of the dispute was also found in the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

The tribunal rejected the ECT as applicable law, but took into account the legitimate disagreement between the parties as to whether the investment had been made illegally and therefore could not benefit from the protection of the ECT. In concluding its discussion of this complication, the tribunal noted that, “to the extent the Parties both took positions as to the propriety of the Respondent’s conduct under the ECT, for this reason alone the Tribunal will consider the ECT when addressing the existence and legality of an investment under each of the BIT and the ECT and Respondent’s compliance with both the BIT and the ECT.” (para. 278).

Indirect expropriation claim is unanimously dismissed

The claimant submitted that Albania had indirectly expropriated its investment under both under the BIT and the ECT. It relied on the following key facts: in June 2000, Durrës was re-zoned to exclude the investment; in July 2000, the investor was ordered to suspend construction of the tank farm, which was subsequently re-authorized; and, as of July 2009, Durrës was closed to petroleum vessels.

The tribunal disagreed, finding that re-zoning was transportation policy and that in any case the claimant had been allowed to operate profitably until the port was closed in 2009. It pointed out that “[r]egulations that reduce the profitability of an investment but do not shut it down completely and leave the investor in control will generally not qualify as indirect expropriations” (para. 572), referencing El Paso v. Argentina.

Majority dismisses FET- and discrimination-based claims

The majority (Rolf Knieper and Yas Banifatemi) noted that Albania’s recent history—“a highly repressive and isolationist communist regime” followed by “a severe economic financial crisis” (para. 625)—was relevant to the FET obligation under the BIT, especially the obligation to provide a stable and transparent legal framework. For the majority, Mamidoil knew that Albania was a country with run down infrastructure and a problematic legal and regulatory framework, and could not therefore legitimately expect the same stability as in other jurisdictions.

In terms of unreasonable and discriminatory measures, for the majority “the State’s conduct bore a reasonable relationship to some rational policy. […] Finally, the closure did not favour a local competitor because it concerned all importers of petroleum products” (para. 791).

Dissenting arbitrator finds violation of FET standard

The dissenting arbitrator (Stephen Hammond) disagreed with the majority’s conclusion that Albania provided fair and equitable treatment. The dissent disagreed with several important factual findings in the award, for example, that the claimant was aware that transformation of the port was imminent when it began construction of the tank farm.

The dissent also disagreed with the legal implications of continued construction after notification of imminent re-zoning. Citing the award in MTD v. Chile, it suggested that this was a mere failure to mitigate and could not result in a forfeiture of treaty rights. In terms of legitimate expectations specifically, the dissent found that the relevant time for determination of whether legitimate expectations had been created was the moment when the decision to invest was made.

Dissent finds violation of Energy Charter’s prohibition on unreasonable and discriminatory measures

The dissent found that Albania’s ban of fuel vessels at Durrës resulted in a failure to accord fair and equitable treatment and also constituted a breach of the ECT’s prohibition on unreasonable and discriminatory measures. While Albania maintained that its decision to ban fuel tankers at Durrës was based on public policy considerations, Mamidoil contended that it was instead driven by the need to settle another arbitration, this time under contract at the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris. Mr. Hammond agreed that the available documents showed the ban to have been triggered by Albania’s settlement agreement. (The majority had found in the award that the settlement agreement reiterated the government’s policy objectives.)

Notes: The tribunal was composed of Rolf Knieper (President appointed by the Chairman of the ICSID Administrative Counsel, German national), Stephen A. Hammond (claimant’s appointee, U.S. national), and Yas Banifatemi (respondent’s appointee, French national). The final award of March 30, 2015 is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4228.pdf. The dissenting opinion of March 20, 2015 is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4235.pdf.

Tribunal found Mongolia liable for unlawful expropriation and awarded more than US$80 million in damages

Khan Resources Inc., Khan Resources B.V. and CAUC Holding Company Ltd. v. The Government of Mongolia and MonAtom LLC, PCA Case No. 2011-09

Joe Zhang[*]

In an award dated March 2, 2015, a tribunal under the arbitration rules of the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) found Mongolia illegally expropriated the assets of foreign investors in breach of its Foreign Investment Law and the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). The claimants were awarded compensation of US$80 million plus interest and costs.

The claimants and the project

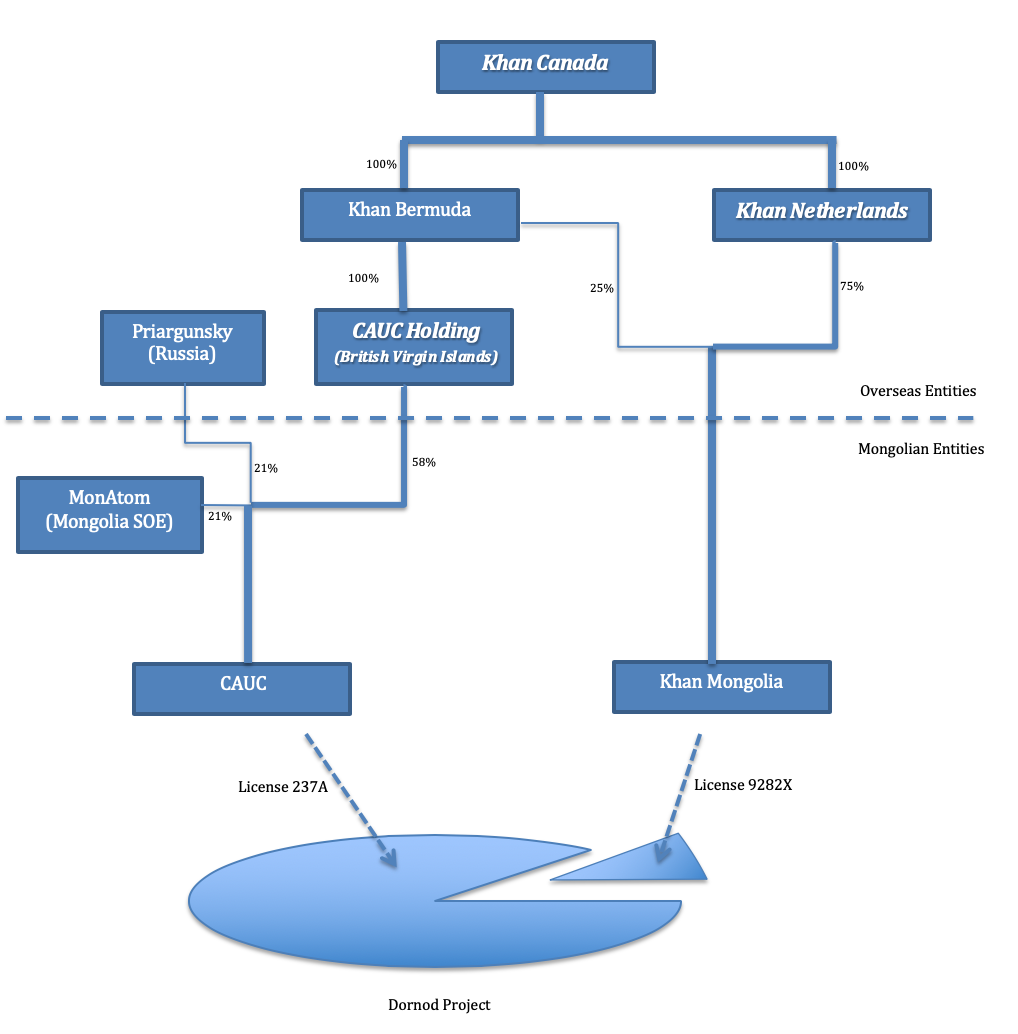

The arbitration was brought by three claimants for their investment in a uranium exploration and extraction project in the Mongolian province of Dornod (the Dornod Project). The claimants were (1) CAUC Holding Company Ltd (CAUC Holding), a British Virgin Islands (BVI) company investing in the Dornod Project through its majority-owned Mongolian subsidiary Central Asian Uranium Company (CAUC); (2) Kahn Resources B.V. (Kahn Netherlands), a Dutch company investing in the Dornod Project through its fully-owned Mongolian subsidiary Khan Resources LLC (Kahn Mongolia); and (3) Kahn Resources Inc. (Kahn Canada), a Canadian company that wholly owns both CAUC Holding, through a Bermuda vehicle, and Kahn Netherlands.

CAUC operated in the Dornod Project under a mining license (License 237A) what initially covered two deposits, but which later, on CAUC’s application, was reduced to exclude a segment aimed at tax and fee savings. Such excluded segment was later acquired by Kahn Mongolia and covered by a separate mining license (License 9282X).

The figure below illustrates the ownership structure of the companies involved immediately before the disputes arose.

The disputes

In 2009, as part of its nuclear energy reform, Mongolia enacted a Nuclear Energy Law (NEL) and established a Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA). In October 2009, NEA issued Decree No. 141, which suspended 149 uranium exploration and exploitation licenses, including Licenses 237A and 9282X, pending confirmation from NEA of their re-registration under the NEL. In March 2010, NEA inspected the Dornod Project site, noting that the project failed to remedy certain previously identified violations of Mongolian law and listing further breaches. In April 2010, NEA invalidated both mining licenses, and declared later that year that it would not re-register to the claimants.

The claimants initiated the arbitration in 2011, relying on three different instruments. Khan Canada and CAUC Holding invoked the arbitration clause of the joint venture agreement that created CAUC (Founding Agreement), claiming the suspension and invalidation of the licenses constituted an unlawful expropriation, in breach of Mongolia’s obligations under the Founding Agreement, Mongolian law (including the Foreign Investment Law), and customary international law. Khan Netherlands relied solely on the ECT, claiming that, by violating the Foreign Investment Law, Mongolia also breached its commitment under the ECT through the operation of the treaty’s umbrella clause.

Jurisdictional challenges

In a separate Decision on Jurisdiction issued on July 25, 2012, the tribunal had ruled on several jurisdictional challenges raised by Mongolia.

Non-signatory becomes “real party” to the arbitration clause by “common intention”

Mongolia objected to the tribunal’s personal jurisdiction over Khan Canada, which was not a party to the Founding Agreement. While noting that the Canadian compliant was indeed not a signatory, the tribunal held that a non-signatory could become a “real party” to the agreement if this was the common intention of the signatory and non-signatory parties. The tribunal found such common intention based on evidence that Khan Canada had assisted CAUC Holding in performing its financial obligations under the Founding Agreement and that various non-official exchanges had in some occasions referred to Khan Canada, instead of its BVI subsidiary CAUC Holding, as one of the shareholders of CAUC.

Sovereign commitment made by state-owned enterprise binding on Mongolia

Mongolia further argued that it should not be bound by the arbitration clause of the Founding Agreement, to which it was not a party. Relying on testimony provided by the claimants’ legal expert, the tribunal found that one of CAUC’s shareholders, MonAtom, a Mongolian company wholly owned by the state, acted as Mongolia’s representative and undertook obligations that only a sovereign state could fulfill, namely, committing to reduce the natural resource utilization fees to be paid by CAUC, thereby giving the tribunal personal jurisdiction over Mongolia under the Founding Agreement.

Broad arbitration clause opens door to claims based on contract, domestic law and customary international law

Mongolia also disputed the tribunal’s subject matter jurisdiction over the claims under the Founding Agreement. However, the tribunal found the broadly drafted arbitration clause of the Founding Agreement covered all claims raised, including claims to breaches of domestic law and customary international law, as they were all sufficiently connected to the Founding Agreement.

Denial of benefits clause of the ECT must be actively exercised before the commencement of arbitration

In terms of the claims raised by Khan Netherlands under the ECT, Mongolia argued that these claims were barred, as ECT Article 17(1) allowed it to deny treaty benefits to investors with “no substantial business activities” in the home state. The tribunal began its analysis of the issue by noting that this was a question of merit, not jurisdiction, as Article 17(1) only concerned Part III (Investment Promotion and Protection) of the ECT, not its Dispute Settlement Chapter (Part V). Even so, the tribunal went on and discussed (a) whether Article 17(1) constituted an automatic denial of benefits and, (b) if not, whether the right to deny benefits may be exercised after the commencement of arbitration. The tribunal largely followed the decisions in Yukos v. Russia and Plama v. Bulgaria, considering it had “a duty to take account of these decisions, in the hope of contributing to the formation of a consistent interpretation of the ECT capable of enhancing the ability of investors to predict the investment protection which they can expect to benefit from under the Treaty” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 417). The tribunal held that a state must actively exercise its right under ECT Article 17(1), and that such active exercise must be in time to give adequate notice to investors, so there would be no lack of certainly to “impede the investor’s ability to evaluate whether or not to make an investment in any particular state” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 426).

Unlawful expropriation claims

A large portion of the tribunal’s analysis on the merits was devoted to the claims of unlawful expropriation, that is, whether the invalidation of the mining licenses and failure to re-register them constituted an unlawful expropriation under Mongolia’s Foreign Investment Law.

Tribunal disagrees with Mongolia on the interpretation of Mongolian law

Mongolia first argued that the mining licenses were not covered investments under its Foreign Investment Law, which defined “foreign investment” as “every type of tangible and intangible property.” Mongolia further argued that mining licenses were not property under Mongolian law, as a decision of the Mongolian Supreme Court has held that “[a] mining license […] is possessed but not owned by any entity, and therefore there is no legal ground to consider such mining license to be a property right which is transferable to the ownership of others” (Award on the Merits, para. 303).

Noting there was a “general notion the rights under licenses (as well as contractual rights) to exploit natural resources constitute intangible property” (Award on the Merits, para. 302), the tribunal disagreed with Mongolia’s interpretation of its laws and its Supreme Court decision, and found Mongolia failed to convince it to “depart from the general notion” (Award on the Merits, para. 307).

Tribunal looks at substantive and procedural aspect of the expropriation claims

In its analysis of whether an unlawful expropriation had occurred, the tribunal first noted there were two types of expropriation under Mongolian Law. A khuraakh takes place when a state deprives the owner of his property due to legal breaches or to the use of the property in a manner that endangers the interests of third parties. A daichlakh is a state-ordered deprivation of property where necessary to satisfy an important public need. Given the facts of the case, the tribunal found the invalidation of the licenses and failure to re-register them must be analyzed as a khuraakh under Mongolian law (Award on the Merits, paras. 313–317). Relying on the testimony of the claimants’ legal expert, the tribunal held that, for the khuraakh to have been lawful, (a) it must have had a legal basis and (b) it must have been carried out in accordance with due process of law.

The tribunal first looked at whether Mongolia had a legal basis for the invalidation of the licenses. Disagreeing with Mongolia, it did not find that the claimants breached Mongolian law. After a proportionality analysis, it concluded that the invalidation of the licenses was not an appropriate penalty, even if the alleged violations had existed. Therefore, the tribunal found Mongolia failed to “point to any breaches of Mongolian law that would justify the decisions to invalidate and not re-register” the mining licenses (Award on the Merits, para. 319). Further, it found, based on evidence presented by the claimants, that the alleged breaches were pretexts for Mongolia’s real motive to “[develop] the Dornod deposits at greater profit with a Russian partner” (Award on the Merits, para. 340).

Turning to the procedural requirement, the tribunal found that the claimants were denied due process of law. In particular, it found Mongolia had an obligation to re-register the mining licenses as there was “no legally significant reason why the Claimants would not have fulfilled the [prescribed] application requirements” (Award on the Merits, paras. 350, 358). The tribunal further found that, since the mining licenses were never re-registered under the newly enacted NEL, the invalidation procedure provided in the NEL would not apply to those mining licenses, and NEA did not have authority to invalidate the licenses unless they were re-registered under the NEL (Award on the Merits, paras. 352–365).

Mongolia breached ECT by operation of umbrella clause

After concluding that Mongolia “breached its obligation under the Foreign Investment Law” (Award on the Merits, para. 366), the tribunal swiftly found Mongolia also liable toward Khan Netherlands under the ECT through operation of the umbrella clause (Award on the Merits, para. 366). It cited to its Decision on Jurisdiction, which had held that “a breach by Mongolia of any obligations it may have under the Foreign Investment Law would constitute a breach of the provisions of Part III of the [ECT]” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 438).

Damages

In calculating the damages, the tribunal rejected traditional methodologies proposed by the parties and decided to value the investment analyzing three offers received between 2005 and 2010 to purchase the Dornod Project, thus reaching a final amount of US$80 million in damages. The tribunal also awarded interest at a rate of LIBOR plus 2 per cent compounded annually from July 1, 2009 (the date of valuation) until the date of payment. In addition, the tribunal awarded the claimants legal fees and costs of US$9.07 million, including a “success fee” based on the contingent fee arrangement between the claimants and their counsel.

Notes

The Tribunal was composed of David A. R. Williams (President appointed by the agreement of co-arbitrators, New Zealander national), L. Yves Fortier (claimants’ appointee, Canadian national), and Bernard Hanotiau (respondents’ appointee, Belgian national). The Decision on Jurisdiction is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4268.pdf. The Award on the Merits is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4267.pdf.

Martin Dietrich Brauch is an International Law Advisor and Associate of IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program, based in Latin America.

Marquita Davis is a Geneva International Fellow from University of Michigan Law and an extern with IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program.

Matthew Levine is a Canadian lawyer and a contributor to IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program.

Joe Zhang is a Law Advisor to IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program.