Tribunal found Mongolia liable for unlawful expropriation and awarded more than US$80 million in damages

Khan Resources Inc., Khan Resources B.V. and CAUC Holding Company Ltd. v. The Government of Mongolia and MonAtom LLC, PCA Case No. 2011-09

In an award dated March 2, 2015, a tribunal under the arbitration rules of the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) found Mongolia illegally expropriated the assets of foreign investors in breach of its Foreign Investment Law and the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). The claimants were awarded compensation of US$80 million plus interest and costs.

The claimants and the project

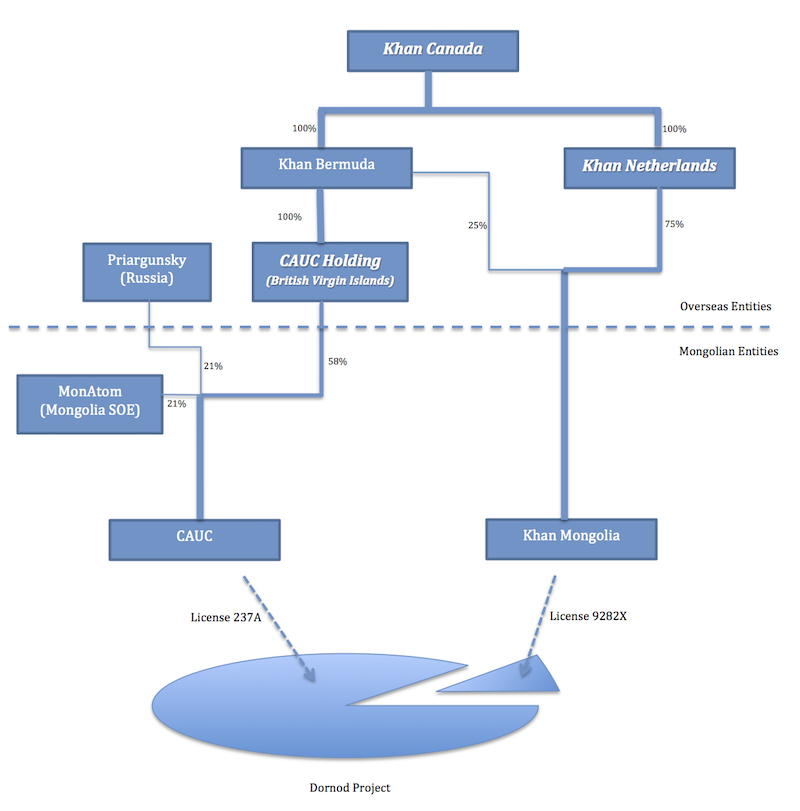

The arbitration was brought by three claimants for their investment in a uranium exploration and extraction project in the Mongolian province of Dornod (the Dornod Project). The claimants were (1) CAUC Holding Company Ltd (CAUC Holding), a British Virgin Islands (BVI) company investing in the Dornod Project through its majority-owned Mongolian subsidiary Central Asian Uranium Company (CAUC); (2) Kahn Resources B.V. (Kahn Netherlands), a Dutch company investing in the Dornod Project through its fully-owned Mongolian subsidiary Khan Resources LLC (Kahn Mongolia); and (3) Kahn Resources Inc. (Kahn Canada), a Canadian company that wholly owns both CAUC Holding, through a Bermuda vehicle, and Kahn Netherlands.

CAUC operated in the Dornod Project under a mining license (License 237A) what initially covered two deposits, but which later, on CAUC’s application, was reduced to exclude a segment aimed at tax and fee savings. Such excluded segment was later acquired by Kahn Mongolia and covered by a separate mining license (License 9282X).

The figure below illustrates the ownership structure of the companies involved immediately before the disputes arose.

The disputes

In 2009, as part of its nuclear energy reform, Mongolia enacted a Nuclear Energy Law (NEL) and established a Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA). In October 2009, NEA issued Decree No. 141, which suspended 149 uranium exploration and exploitation licenses, including Licenses 237A and 9282X, pending confirmation from NEA of their re-registration under the NEL. In March 2010, NEA inspected the Dornod Project site, noting that the project failed to remedy certain previously identified violations of Mongolian law and listing further breaches. In April 2010, NEA invalidated both mining licenses, and declared later that year that it would not re-register to the claimants.

The claimants initiated the arbitration in 2011, relying on three different instruments. Khan Canada and CAUC Holding invoked the arbitration clause of the joint venture agreement that created CAUC (Founding Agreement), claiming the suspension and invalidation of the licenses constituted an unlawful expropriation, in breach of Mongolia’s obligations under the Founding Agreement, Mongolian law (including the Foreign Investment Law), and customary international law. Khan Netherlands relied solely on the ECT, claiming that, by violating the Foreign Investment Law, Mongolia also breached its commitment under the ECT through the operation of the treaty’s umbrella clause.

Jurisdictional challenges

In a separate Decision on Jurisdiction issued on July 25, 2012, the tribunal had ruled on several jurisdictional challenges raised by Mongolia.

Non-signatory becomes “real party” to the arbitration clause by “common intention”

Mongolia objected to the tribunal’s personal jurisdiction over Khan Canada, which was not a party to the Founding Agreement. While noting that the Canadian compliant was indeed not a signatory, the tribunal held that a non-signatory could become a “real party” to the agreement if this was the common intention of the signatory and non-signatory parties. The tribunal found such common intention based on evidence that Khan Canada had assisted CAUC Holding in performing its financial obligations under the Founding Agreement and that various non-official exchanges had in some occasions referred to Khan Canada, instead of its BVI subsidiary CAUC Holding, as one of the shareholders of CAUC.

Sovereign commitment made by state-owned enterprise binding on Mongolia

Mongolia further argued that it should not be bound by the arbitration clause of the Founding Agreement, to which it was not a party. Relying on testimony provided by the claimants’ legal expert, the tribunal found that one of CAUC’s shareholders, MonAtom, a Mongolian company wholly owned by the state, acted as Mongolia’s representative and undertook obligations that only a sovereign state could fulfill, namely, committing to reduce the natural resource utilization fees to be paid by CAUC, thereby giving the tribunal personal jurisdiction over Mongolia under the Founding Agreement.

Broad arbitration clause opens door to claims based on contract, domestic law and customary international law

Mongolia also disputed the tribunal’s subject matter jurisdiction over the claims under the Founding Agreement. However, the tribunal found the broadly drafted arbitration clause of the Founding Agreement covered all claims raised, including claims to breaches of domestic law and customary international law, as they were all sufficiently connected to the Founding Agreement.

Denial of benefits clause of the ECT must be actively exercised before the commencement of arbitration

In terms of the claims raised by Khan Netherlands under the ECT, Mongolia argued that these claims were barred, as ECT Article 17(1) allowed it to deny treaty benefits to investors with “no substantial business activities” in the home state. The tribunal began its analysis of the issue by noting that this was a question of merit, not jurisdiction, as Article 17(1) only concerned Part III (Investment Promotion and Protection) of the ECT, not its Dispute Settlement Chapter (Part V). Even so, the tribunal went on and discussed (a) whether Article 17(1) constituted an automatic denial of benefits and, (b) if not, whether the right to deny benefits may be exercised after the commencement of arbitration. The tribunal largely followed the decisions in Yukos v. Russia and Plama v. Bulgaria, considering it had “a duty to take account of these decisions, in the hope of contributing to the formation of a consistent interpretation of the ECT capable of enhancing the ability of investors to predict the investment protection which they can expect to benefit from under the Treaty” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 417). The tribunal held that a state must actively exercise its right under ECT Article 17(1), and that such active exercise must be in time to give adequate notice to investors, so there would be no lack of certainly to “impede the investor’s ability to evaluate whether or not to make an investment in any particular state” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 426).

Unlawful expropriation claims

A large portion of the tribunal’s analysis on the merits was devoted to the claims of unlawful expropriation, that is, whether the invalidation of the mining licenses and failure to re-register them constituted an unlawful expropriation under Mongolia’s Foreign Investment Law.

Tribunal disagrees with Mongolia on the interpretation of Mongolian law

Mongolia first argued that the mining licenses were not covered investments under its Foreign Investment Law, which defined “foreign investment” as “every type of tangible and intangible property.” Mongolia further argued that mining licenses were not property under Mongolian law, as a decision of the Mongolian Supreme Court has held that “[a] mining license […] is possessed but not owned by any entity, and therefore there is no legal ground to consider such mining license to be a property right which is transferable to the ownership of others” (Award on the Merits, para. 303).

Noting there was a “general notion the rights under licenses (as well as contractual rights) to exploit natural resources constitute intangible property” (Award on the Merits, para. 302), the tribunal disagreed with Mongolia’s interpretation of its laws and its Supreme Court decision, and found Mongolia failed to convince it to “depart from the general notion” (Award on the Merits, para. 307).

Tribunal looks at substantive and procedural aspect of the expropriation claims

In its analysis of whether an unlawful expropriation had occurred, the tribunal first noted there were two types of expropriation under Mongolian Law. A khuraakh takes place when a state deprives the owner of his property due to legal breaches or to the use of the property in a manner that endangers the interests of third parties. A daichlakh is a state-ordered deprivation of property where necessary to satisfy an important public need. Given the facts of the case, the tribunal found the invalidation of the licenses and failure to re-register them must be analyzed as a khuraakh under Mongolian law (Award on the Merits, paras. 313–317). Relying on the testimony of the claimants’ legal expert, the tribunal held that, for the khuraakh to have been lawful, (a) it must have had a legal basis and (b) it must have been carried out in accordance with due process of law.

The tribunal first looked at whether Mongolia had a legal basis for the invalidation of the licenses. Disagreeing with Mongolia, it did not find that the claimants breached Mongolian law. After a proportionality analysis, it concluded that the invalidation of the licenses was not an appropriate penalty, even if the alleged violations had existed. Therefore, the tribunal found Mongolia failed to “point to any breaches of Mongolian law that would justify the decisions to invalidate and not re-register” the mining licenses (Award on the Merits, para. 319). Further, it found, based on evidence presented by the claimants, that the alleged breaches were pretexts for Mongolia’s real motive to “[develop] the Dornod deposits at greater profit with a Russian partner” (Award on the Merits, para. 340).

Turning to the procedural requirement, the tribunal found that the claimants were denied due process of law. In particular, it found Mongolia had an obligation to re-register the mining licenses as there was “no legally significant reason why the Claimants would not have fulfilled the [prescribed] application requirements” (Award on the Merits, paras. 350, 358). The tribunal further found that, since the mining licenses were never re-registered under the newly enacted NEL, the invalidation procedure provided in the NEL would not apply to those mining licenses, and NEA did not have authority to invalidate the licenses unless they were re-registered under the NEL (Award on the Merits, paras. 352–365).

Mongolia breached ECT by operation of umbrella clause

After concluding that Mongolia “breached its obligation under the Foreign Investment Law” (Award on the Merits, para. 366), the tribunal swiftly found Mongolia also liable toward Khan Netherlands under the ECT through operation of the umbrella clause (Award on the Merits, para. 366). It cited to its Decision on Jurisdiction, which had held that “a breach by Mongolia of any obligations it may have under the Foreign Investment Law would constitute a breach of the provisions of Part III of the [ECT]” (Decision on Jurisdiction, para. 438).

Damages

In calculating the damages, the tribunal rejected traditional methodologies proposed by the parties and decided to value the investment analyzing three offers received between 2005 and 2010 to purchase the Dornod Project, thus reaching a final amount of US$80 million in damages. The tribunal also awarded interest at a rate of LIBOR plus 2 per cent compounded annually from July 1, 2009 (the date of valuation) until the date of payment. In addition, the tribunal awarded the claimants legal fees and costs of US$9.07 million, including a “success fee” based on the contingent fee arrangement between the claimants and their counsel.

Notes

The Tribunal was composed of David A. R. Williams (President appointed by the agreement of co-arbitrators, New Zealander national), L. Yves Fortier (claimants’ appointee, Canadian national), and Bernard Hanotiau (respondents’ appointee, Belgian national). The Decision on Jurisdiction is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4268.pdf. The Award on the Merits is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4267.pdf.

Author

Joe Zhang is a Law Advisor to IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program.