Towards a New Generation of Investment Policies: UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development

On 12 June 2012, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) launched its Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development (IPFSD or the framework).

IPFSD comes at a time when the international investment regime is in a state of « transition »[1] and when an increasing number of governments are reviewing their investment-related regulatory frameworks, both at the national and international levels. With respect to international investment policies, this evolution has been fuelled by a surge of academic and policy debates discussing—and sometimes questioning—the sustainable development orientation of the 3,000-plus international investment agreements (IIAs).[2] The IPFSD is UNCTAD’s response to these debates and concerns.

What is the framework?

The framework, which also constitutes the main substantive theme of the 2012 World Investment Report (WIR), consists of a comprehensive guide for national and international investment policy making. Its eleven core principles first set the stage and are then converted into guidelines for national investment policies and policy options for IIAs.

The framework provides policymakers with concrete options for placing inclusive growth and sustainable development at the heart of efforts to attract and benefit from foreign investment. In so doing, the framework aims at creating synergies between investment policies and wider economic development goals; promoting the integration of investment policies into development strategies; fostering responsible investment and incorporating principles of corporate social responsibility (CSR); and ensuring policy effectiveness in the design and implementation of investment policies.

IPFSD reflects the notion that investment policies are made with a view of attracting foreign capital, but adds to that a broader and more intricate development policy agenda of factoring in sustainable development and inclusive growth into national investment regulations and international investment negotiations.

The timeliness of the framework

IPFSD comes at a time when investment policymaking is in a state of flux. Nationally, policymaking is moving from an era of liberalization to an era of regulation.[3] At the international level, there have been growing concerns that IIAs can interfere with countries’ sustainable development strategies and prevent them from implementing policies that address the environmental and social impact of investments. Critics have argued that this is the result of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms found in IIAs, which allow investors to sue host States, and are sometimes used in areas that involve crucial public policy measures. ISDS cases launched by Philip Morris against Australia and Uruguay regarding their tobacco control measures or by Vattenfall against Germany for its nuclear power phase-out plan are examples in point.[4]

As a response, some countries, such as Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela, withdrew from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID);[5] Australia issued a trade policy statement announcing that it would stop including ISDS clauses in its future IIAs; and others responded by drafting new IIAs that include mechanisms that retain their right to regulate investment in the public interest (e.g., regarding the protection of the environment and public health and safety), or which otherwise aim to reduce the risk of exposure to litigation by foreign investors. Along these lines, sustainable development elements are gaining prominence in international investment policies.[6]

As the development community is looking for a new development paradigm and seeking ways and means to factor sustainable development and inclusive growth into national investment regulations and international negotiations, the IPFSD becomes the ultimate tool to consult and use.

The framework’s policy options for IIAs

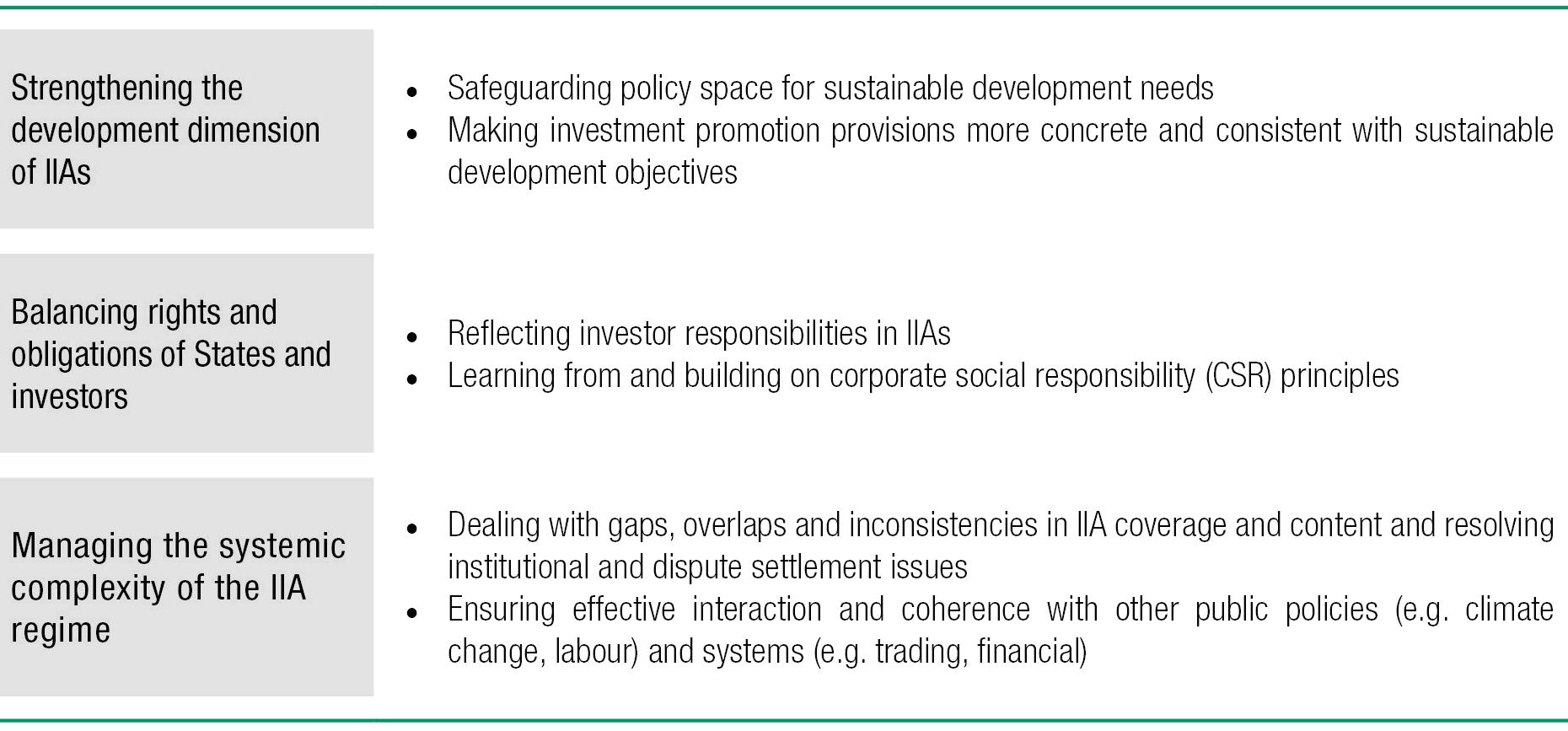

With respect to international investment policymaking, the IPFSD identifies three main challenges and provides respective responses (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. International investment policy challenges

It then provides three comprehensive tables, setting out 115 plus explicit policy options among which governments can choose those that best suit their countries’ levels of development and respective policy objectives. Among others, the three tables include: proposed adjustments of existing IIA provisions to make them more sustainable development-friendly through formulations that safeguard policy space and limit State liability; the addition of new provisions in IIAs, for instance, to balance investor rights and responsibilities and to promote responsible investment; and the introduction of Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) clauses for the less developed Party to calibrate the level of obligations to the country’s level of development.

Among the 115 plus options, IPFSD also identifies those options that could be particularly supportive of sustainable development. These include:

- a carefully crafted scope-and-definition clause that excludes portfolio, short-term or speculative investments from treaty coverage;

- the formulation of the fair and equitable treatment (FET) clause as an exhaustive list of State obligations (e.g. not to (i) deny justice in judicial or administrative procedures, (ii) treat investors in a manifestly arbitrary manner, (iii) flagrantly violate due process);

- the clarification (to the extent possible) of the distinction between legitimate regulatory activity and regulatory takings that give rise to compensation (indirect expropriations);

- the limitation of the Full Protection and Security (FPS) clause to establish that “physical” security and protection will only commensurate with the country’s level of development;

- the limitation of the scope of the transfer-of-funds clause by providing an exhaustive list of covered payments/transfers, the inclusion of exceptions that are triggered in the event that there are serious balance-of-payment difficulties, and the stipulation that the transfer right of the investor is contingent on the latter’s compliance with the fiscal and other transfer-related obligations of the host country;

- the inclusion of carefully crafted exceptions to protect human rights, health, core labour standards and the environment, along with a check-and-balance system that makes sure there is enough policy space whilst avoiding abuse; and

- the option of “no ISDS mechanisms” clauses, or clauses designed to make ISDS the last resort (e.g. after exhaustion of local remedies and the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution mechanisms by the investors).

The framework also proposes the establishment of an institutional set-up that will be responsible to ensure that the IIA is adaptable to changing development contexts and major unanticipated developments (for example, by using adhoc committees to assess the effectiveness of the agreement and to further improve its implementation through amendments or interpretations).

Through all of these, the framework operates lucidly, putting particular emphasis on the relationship between foreign investment and sustainable development, advocating a balanced approach between the pursuit of purely economic growth objectives by means of investment liberalization and promotion, on the one hand, and the need to protect people and the environment on the other.

Modus operandi of the framework

The framework has been well received by investment and development stakeholders, including at the highest level of policymaking, in the academic circle and by investment experts and civil society organizations. For example, UNCTAD’s IIA Conference and the Ministerial Round Table (MRT) at UNCTAD’s biennial 2012 World Investment Forum (WIF)[7] both discussed an advanced version of the framework. Ministers, for example, advocated a new generation of investment policies and called for the development of a set of core principles for national and international investment policies. IIA experts also agreed that IIAs should cater to broader objectives such as sustainable development, human rights and other important public concerns.

Since then, IPFSD, as part of the WIR 2012, has been launched in more than 44 countries, including during a joint UNCTAD-IISD discussion event for investment and development stakeholders.[8]

Among others, IPFSD’s attractiveness for a broad range of stakeholders may lie in its special way of operating. For instance, the framework is not a model treaty, but rather a platform where a wide variety of options are offered. Policy makers can choose the ones that they consider best suited to their country’s special development needs. Secondly, many of the policy options suggested draw upon innovative State practices; for instance, fifteen of the 47 IIAs signed in 2011 already include elements similar to the sustainable development enhancing features suggested in the IPFSD.[9]

Third, the IPFSD is a “living document” designed to be further developed through an inclusive dialog and dynamic investment policymaking. For that purpose, UNCTAD created a discussion platform that provides investment stakeholders and the international development community (e.g. policymakers, investors, business associations, labour unions, civil society organizations and other relevant interest groups) an opportunity to consult, discuss and share experiences and views with each other. This platform is also the essence of the new Investment Policy Hub[10], which gives the framework a « living document » flavor through an online discussion forum.

In the future, the framework will also be used as the basis of UNCTAD’s technical assistance activities on IIAs. First experiences were already gained this summer when UNCTAD contributed to a training convened by IISD and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) for the drafting of a SADC Model BIT template.[11]

Through all of this, UNCTAD hopes that the framework will be used as a key point of reference for policymakers in formulating national investment policies and in negotiating or reviewing IIAs. As such, the framework can operate as a point of convergence for international cooperation on investment issues with a view to fostering sustainable development and inclusive growth.

Authors: Elisabeth Tuerk is Officer-in-Charge and Faraz Rojid, Legal Consultant, in the International Investment Agreements (IIA) Section of the Division on Investment and Enterprise (DIAE), UNCTAD.

[1] Jose E. Alvarez, Karl P. Sauvant, Kamil Girard Ahmed, and Gabriela P. Vizcaino, The Evolving International Investment Regime: Expectations, Realities, Options, Oxford University Press, Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2011; Print ISBN-13: 9780199793624. See also Chapter III of WIR 2012, 2011 and 2010 (http://www.unctad-docs.org/files/UNCTAD-WIR2012-Full-en.pdf, http://www.unctad-docs.org/files/UNCTAD-WIR2011-Full-en.pdf and http://unctad.org/en/Docs/wir2010_en.pdf respectively).

[2] See Chapter III of WIR 2012, WIR 2011 and WIR 2010 (n2).

[3] See Chapter III of WIR 2012 (n2).

[4] See Latest Developments in Investor-State Dispute Settlement, IIA Issues Note No. 1, April 2012, http://www.unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaeia2012d10_en.pdf.

and Chapter III of WIR 2012 (n2).

[5] See Ripinsky, S, Venezuela’s Withdrawal From ICSID: What it Does and Does Not Achieve, ITN, April 13, 2012. Accessed online at http://www.iisd.org/itn/2012/04/13/venezuelas-withdrawal-from-icsid-what-it-does-and-does-not-achieve/

[6] See further Chapter III of the World Investment Report 2012 (n2), at page 87.

[7] The World Investment Forum 2012 was part of the UNCTAD XIII Conference, held in Doha, Qatar in April 2012. Find more information here: http://unctad-worldinvestmentforum.org/

[8] Visit the Investment Policy Hub (http://unctad.org/ipfsd) for a video of the discussion.

[9] See Chapter III, WIR 2012, at page 90.

[10] Please visit http://ipfsd.unctad.org

[11] See the Events Calendar at http://unctad.org/ipfsd for a list of upcoming technical assistance activities.