Nigeria Must Ensure its Fuel Subsidy Reform Sticks for the Long Term

Q&A with Dr. Neil McCulloch, Director of The Policy Practice

Nigeria's new president, Bola Tinubu, removed gasoline subsidies right after he was sworn in on May 29. To find out what this means for Nigeria and how the country can make this reform a success, IISD's Energy Communications expert Aia Brnic talked with fossil fuel subsidy expert Dr. Neil McCulloch, author of the book Ending Fossil Fuel Subsidies: The Politics of Saving the Planet. Neil is Director of The Policy Practice, a network of experienced development professionals, and has co-authored several IISD reports. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Aia Brnic: What's happening in Nigeria with fuel subsidies right now?

Neil McCulloch: Nigeria has just elected a new President, Bola Tinubu, who announced the end of fuel subsidies in his inauguration speech. Nigeria has been subsidizing fuel for more than 40 years, and the one major fuel subsidy left is for gasoline. While this is a very bold thing to do, it is also long overdue. But the inevitable happened—the petrol stations shut up shop because they didn't want to sell fuel until the prices rose, and so suddenly, there were long queues and gasoline shortages. Shortly after, Tinubu announced a new fuel price, which had more than doubled, from about NGN 185 (USD 0.40) to NGN 537 (USD 1.15), due to the removal of fuel subsidies.

Aia Brnic: What is the plan now? Is this it, or is the government planning to go further?

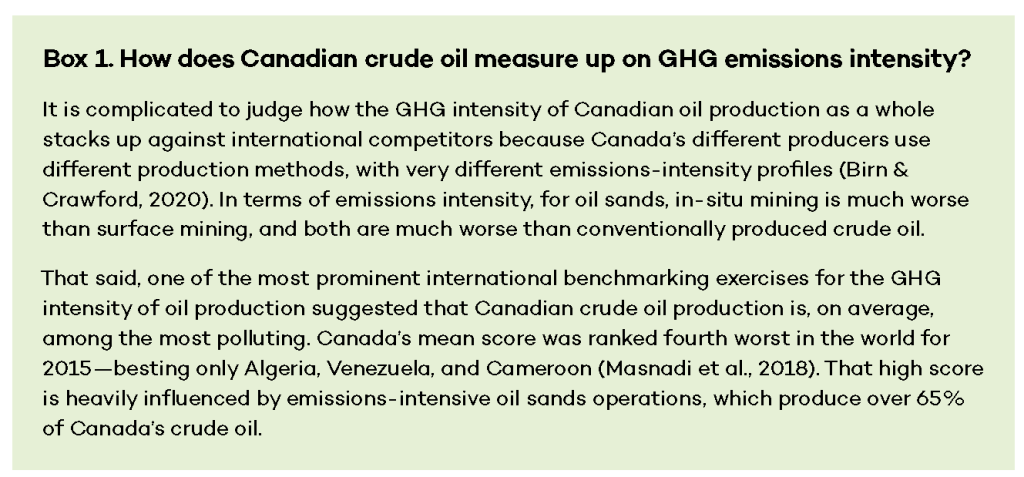

Neil McCulloch: That's a really important question. The problem with Nigerian fuel subsidies has been that the cycle has repeated itself for more than a decade: a new president comes in, realizes that the burden of subsidies on the budget is far too high—Nigeria was spending almost USD 10 billion (NGN 4.39 trillion) last year just on subsidizing gasoline, which is more than four times the health budget (NGN 827 billion)—and takes a bold move to bump up the price. The previous president, Muhammadu Buhari, did the same thing; [former president Goodluck Ebele] Jonathan also tried reform in 2012 with disastrous results.

After the price increase, for a little while, there are no subsidies, but then subsidies always re-emerge because the domestic currency slides relative to the dollar. And as that happens, the cost of fuel goes up—but since the domestic price is fixed, that gap is filled by the budget. Usually, once you've had your one shot at removing subsidies, you don't get another political shot at doing it, so subsidies accumulate, and then they leave it to the next president to do the same thing again. One of the things we will wait to see is whether President Tinubu is going to change the system or just bump up the price as previous presidents did.

Aia Brnic: What has been announced so far?

Neil McCulloch: The regulator announced prices for all the different regions, which was a bit disappointing. I was hoping that he might say to oil marketing companies: "You choose the price; it's a competitive market out there." That would have liberalized the sector. The prices would have been volatile, and they would have jumped around a little bit, but then they would have settled down and continued to evolve depending on the cost of fuel.

But because the regulator now has set prices for different states, it looks like a rerun of the previous arrangements whereby they've just fixed prices, and it'll be quite difficult for them to adjust. The real telltale sign of whether this is a serious reform or not will come in the course of the next month. If they say, "We're going to have a template and we’re going to adjust prices every month according to that template," then they are serious.

Aia Brnic: What blocked fuel subsidy reforms in the past?

Neil McCulloch: Two things have really affected reform. First, it is politically incredibly unpopular to bump up prices in this way. In 2012, when President Jonathan was in power, he did a sudden fuel subsidy reform where he increased prices by roughly three times. And the country erupted. There was a 10-day national strike, everybody was out on the streets, and people got killed. It was a disaster, and eventually, the government had to back down and reduce the price significantly, which meant that by the end of the Jonathan regime, there were still huge subsidies being paid. Everybody in Nigeria has that experience seared into them, and they want to avoid that.

The other reason is that there are vested interests in keeping the subsidy regime. There's a very healthy business to be made smuggling fuel out of Nigeria to the neighbouring countries where, prior to the price bump, it was much, much cheaper. Police and customs officials make a lot of money collaborating with people who wish to smuggle fuel over borders.

Aia Brnic: Given how unpopular and difficult it is to remove fuel subsidies, why is it important to do it? How can regular citizens—who may struggle to pay their bills—accept it?

Neil McCulloch: The standard reason most Westerners would give is that we must stop subsidizing fossil fuels because of climate change. Honestly, that argument doesn’t resonate very well in Nigeria and, indeed, in many poor countries. While it's not that people don’t care about climate change—in fact, many of them are more impacted by climate change than people in wealthier countries—they have more pressing concerns like feeding their families and being able to get to work. So, they appreciate the subsidy and don’t want it removed. And you can totally understand why.

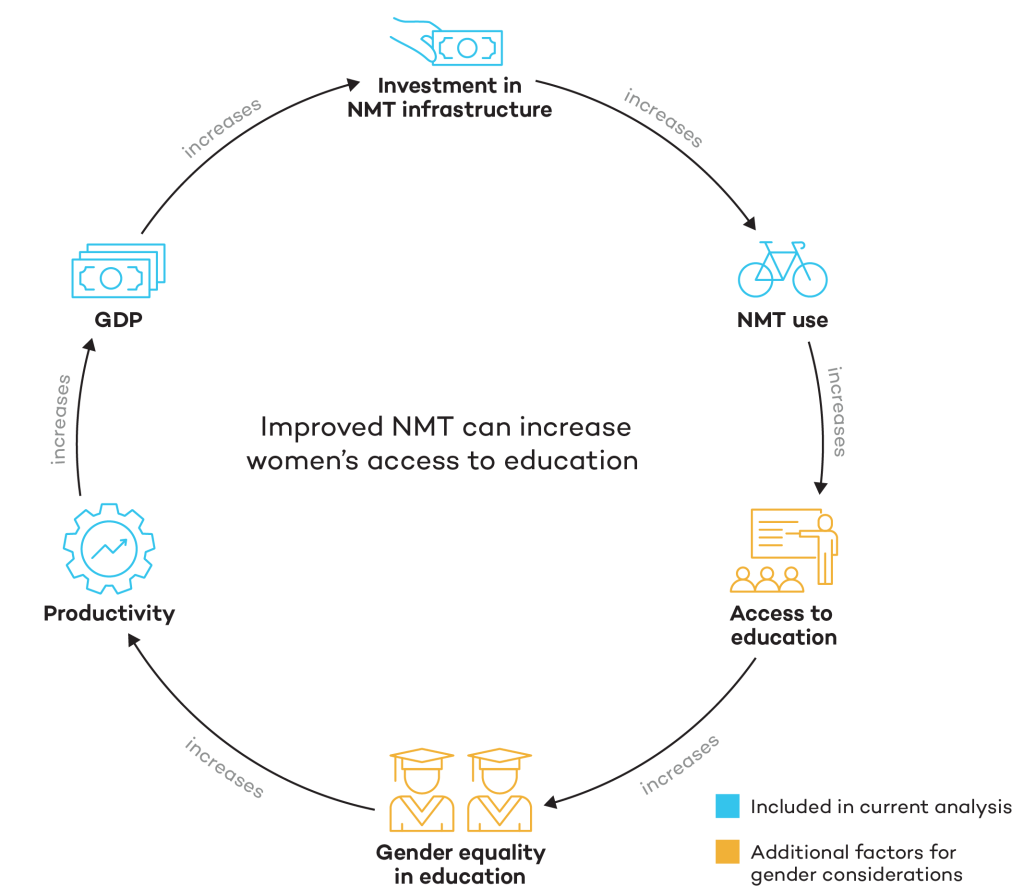

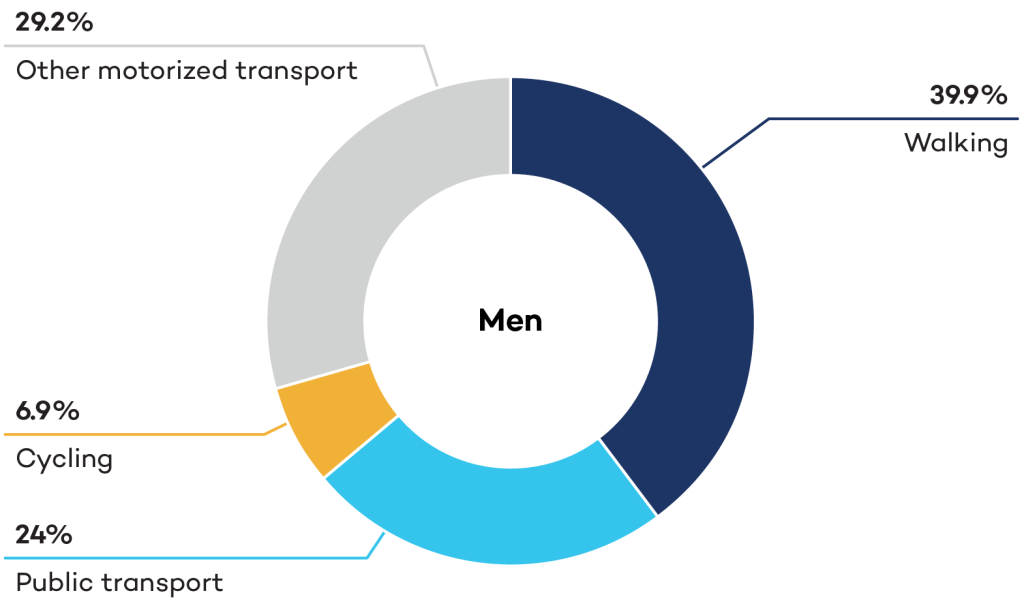

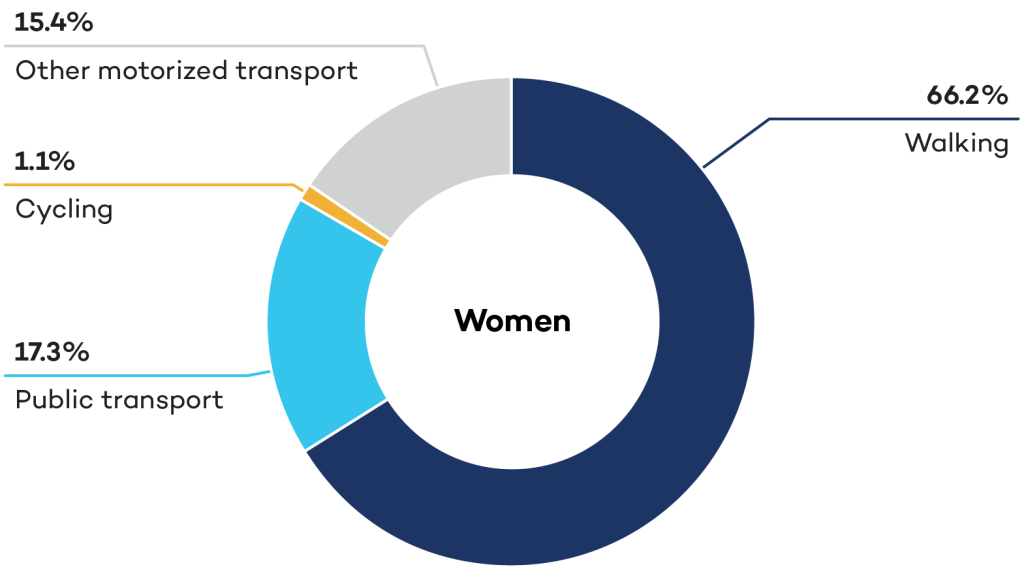

At the same time, spending billions of dollars of the government budget subsidizing gasoline is one of the worst possible ways of spending your money if you care about development and the poor. That's because most of that benefit goes to the better off—people who have cars and motorbikes—rather than ordinary working people who might be on foot or taking buses. These subsidies are very unequal, but they're also not contributing to anything that's useful in the long term, like health services, roads, education systems, and social protection. It's just subsidizing the price, and it makes people burn more gasoline—which, of course, causes all sorts of environmental damage. Unfortunately, reforming subsidies also hurts the poor—not directly because the gasoline price went up, but rather because of the knock-on impact on food prices. And that's an area where the government really has to look out and do something to help people.

Aia Brnic: What is the solution to this?

Neil McCulloch: The standard solution—which the World Bank always pushed—is that there should be cash transfers. In many countries, the World Bank has supported the implementation of cash transfer schemes for the poor and the near-poor. Sometimes these systems are targeted at the bottom 40% of the population. Indonesia has done it, and it turned out that the cash given to the poorest 20% of the population more than compensated them for the petrol price rise. So, they were better off as a result. Having cash transfers, I think, is part of the solution, and the World Bank in Nigeria has been trying to support the government in introducing a similar cash transfer mechanism. If you don't have some sort of compensatory mechanism, then people will be very upset, and rightly so.

However, it's not the only thing. You have got to have mechanisms that reach out to the bulk of the urban working class and the people who aren’t necessarily the poorest of the poor, but who do have to get on a bus, who do have to get to work, who live in Lagos or Abuja and are going to be very severely affected by these kinds of reforms because they buy gasoline. One mechanism, for instance, is for the government to provide explicit temporary subsidies to public transportation, ensuring the bus fares don’t go through the roof when the gasoline price rises. That way, you are enabling people to continue their livelihood.

There are other things, though, that can be done. In countries with successful reforms, we've often found that politicians turn it from a bad thing into a good thing. They have a political offer, and they say, "I'm sorry about this reform, it is very painful, and we'll do everything possible to protect you. But now that we've saved these resources, I'm going to give you something in return." And the thing that they offer is deliberately something that is very politically popular. For example, in the Indonesian case, that was a health card and an education card. Zambia recently made a major reform in 2021, and they said, "We're going to give you free secondary school education." This offer was very popular because secondary school education is expensive, but the cost of the subsidies was way more than the cost of secondary school education. So, the idea is to redirect funds toward something that is very popular. Having a political offer moves the story away from being a negative one to being, "This government is giving us something that’s very important." The Nigerian government needs quickly to come up with a politically credible offer so that it can say to Nigerians, "We’re going to make things better, and here’s how."

Aia Brnic: How important is clear communication about the reform?

Neil McCulloch: One of the points I make in my book Ending Fossil Fuel Subsidies is: communication, communication, communication. The presidents and prime ministers who have been successful in making fossil fuel subsidy reforms have generally been the ones who haven’t just suddenly launched it on people but who have talked about it and explained, "This is why it has to be done; this is how we got into this mess, how we’re going to get out of it, and why it’s going to make you better off in the longer run." Building that credibility and explaining to the population diffuses a lot of the anger against reform. If you don’t communicate and you launch it on people suddenly, then they are understandably angry and then they take to the streets. Who wouldn't? We saw this not just in developing countries but also in France with the gilets jaunes [(yellow vests) movement in 2018]. It’s really important that the government communicates these things in advance and makes sure that people understand why the reform is being done, even if it is unpopular.

Aia Brnic: The world is still in the middle of a cost-of-living crisis. Is this good or bad timing for such reform?

Neil McCulloch: It's a terrible time for the reform, but I think that President Tinubu has no real choice but to take these difficult steps now. Nigeria's finances are in a terrible state, partly because of the perpetuation of this subsidy. He must take bold measures—and the only time he can realistically take them is within the first 6 months of his presidency. But that's why it's so important that he and his government also provide measures to protect the people. I believe they are thinking seriously about that. The question is how they go about it. The inauguration speech mentioned several measures about jobs and prosperity. I think President Tinubu is right to focus on getting the economics and macroeconomics right, and fixing fossil fuel subsidies is one of the most important things he can do. But that’s not going to make it easy in the short term, particularly because prices are already rising.

Aia Brnic: How can Nigeria do things right this time?

Neil McCulloch: The number one thing, in my view, is to change the system. This is my big concern and my big hope as well. President Tinubu is a very smart man. He was very successful as Governor of Lagos, and he understands the depth and nature of the problems that Nigeria faces. So I hope that he will really grasp the nettle and recognize that gasoline is a commodity, just like every other commodity, and that its price needs to vary with the price in the world market in order to ensure that subsidies never re-emerge—because there are much better things for the Nigerian government to spend its subsidies on. It could spend them on promoting jobs, having an industrial development strategy or an agricultural development strategy that supports farmers, helping the poor ,and building a health service. But it will only have the resources to do that if it stops wasting so much money on subsidizing petrol. I hope that Tinubu doesn't simply bump up the price and that he also changes the system—by either liberalizing it entirely or setting up a template that shifts that price every month, as is done in South Africa, Zambia, Tanzania, and many other African countries. It's really important that he makes sure that this reform sticks for the long term rather than just as a one-off shift.

Aia Brnic: What are the next three things that Nigeria should do, in your opinion, to get this reform done?

Neil McCulloch: Number one, there's got to be a mechanism for compensating Nigerians who will be badly impacted by the current price rise. That is essential because, otherwise, people will be negatively impacted. Number two: make sure it's clear this is not just a bump in price, it's a change in the system, then announce what the new system will be, how the petrol price will be calculated, and how it will change. And make sure it changes at least every month to deal with exchange rate movements and movements in the international market so that subsidies never re-emerge. That is critical. And number three—and this is where it aligns very well with the inauguration speech and all the positive measures that the president is pushing—align the reform with politically popular offers to the population about how jobs will be created and how the services will be delivered. Those three things are vital for making the reform stick.

Aia Brnic: What is the renewable energy sector's potential in Nigeria? Could this reform contribute to building a more sustainable energy sector?

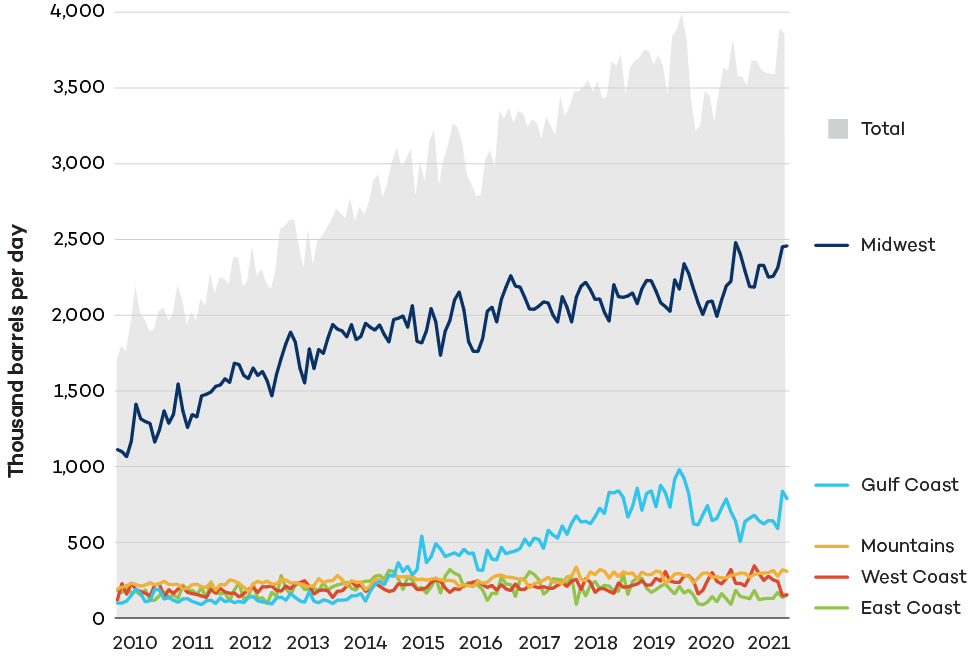

Neil McCulloch: The challenge has always been that the Nigerian electricity system is broken. The distribution companies don't collect enough money for the electricity they sell. They therefore don't pass enough money back to the bulk supplier, then the bulk supplier doesn't pay the generators, and the generators don't generate. Nigeria has 13 gigawatts of [installed] power, but it only actually generates around about 4–5 gigawatts every day. Despair over the power system has meant that a lot of people have just opted out completely—large businesses and households as well—and just built themselves solar panels. Mini-grids and solar are a fantastic solution for a lot of Nigerians, particularly in more remote locations where the grid can't reach, but getting the grid to function effectively for most of the urban areas is the answer—and that's another difficult long-term and very political reform.

Meanwhile, the government has been refusing to supply a sovereign guarantee—which ensures the government will pay the electricity provider if the utility fails to do so—for independent renewable power developers, who, as a result, find it very hard to get financed. So there are all sorts of problems with getting the renewable sector going in Nigeria, and that's one of the reasons why a lot of people are looking at the off-grid rather than the on-grid sector.

Aia Brnic: How can Nigeria build a cleaner and more sustainable energy system?

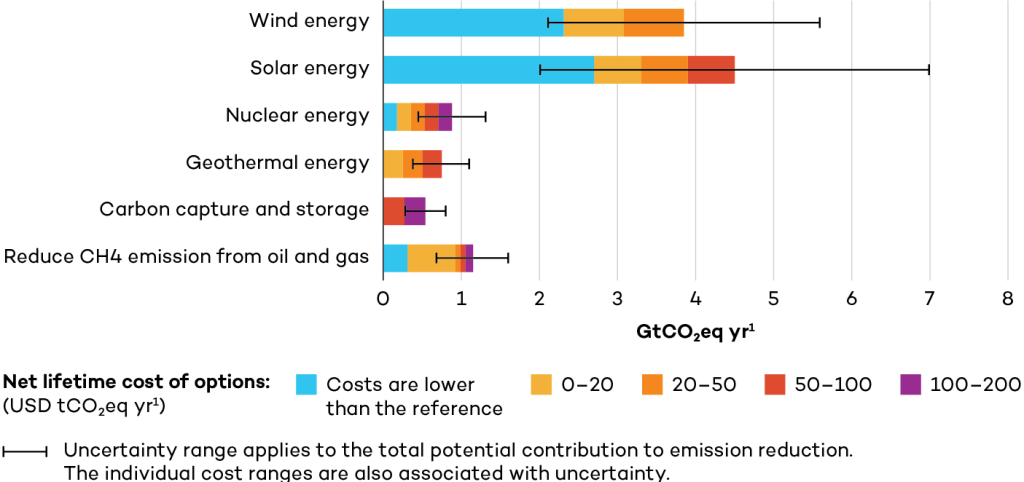

Neil McCulloch: Number one, I think that fossil fuel subsidy reform is a very important part of that because it stops wasting vast resources on fossil fuels and makes [these fuels] reflect their true cost. People will, over time, shift to more efficient vehicles, which reduces fuel usage. And the second thing is to continue to pursue the reforms in the power sector. A lot of good work has been done already, but there really needs to be a way of ensuring that independent power producers can produce and inject their electricity into the system and get paid for it. That could be done either by bilateral contracts between generators and consumers, without necessarily having to go through a central buyer, or by improving the market system of the central buyer. This is going to be one of the central industrial policy challenges of the new government—and if they get that right, the benefits will be enormous. Nigeria is a country of over 200 million people with a 13-gigawatt grid—this is nothing, and it should have a grid 10 times that size. But to get there, it must have a grid that is profitable and self-sustaining so that it can expand. If you get that, suddenly all the solar, wind, and biogas become viable, and investors will be more than willing to invest in them.