Canadian Youth Want to See Stronger Climate Policy in 2024

IISD takes a look at what Canada's Local Conference of Youth is asking of policymakers after COP 28.

The 28th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 28) ended in late 2023, with negotiators heading back to their home countries and member states turning their focus inward to their national climate strategies. However, the discussions on climate policy and strategies don’t end with the COP, and Canadian youth still have a lot to say about what they want to see in the future.

In the months leading up to COP every year, youth from all over the world gather in Local Conferences of Youth (LCOYs), which fall under the UNFCCC’s official youth constituency. Ultimately, they produce policy documents that outline the priorities of young people on climate policy.

Canada’s LCOY in 2023 was hosted by the Human and Nature Youth Club and the Asia Forest Research Centre at the University of British Columbia. It brought together 250 youth from across the country to discuss their priorities in three major areas: sustainable systems, planetary health, and political, societal, and governance practices. They aimed their policy document at Canada’s federal and provincial level governments and focused on changes they would like to see here at home now that negotiations are over.

IISD’s Water Policy and Youth Engagement Officer, Emily Kroft, was one of the youth involved, helping create a policy document outlining key points and demands from Canadian youth on climate policy in Canada.

A Focus on Sustainable Systems

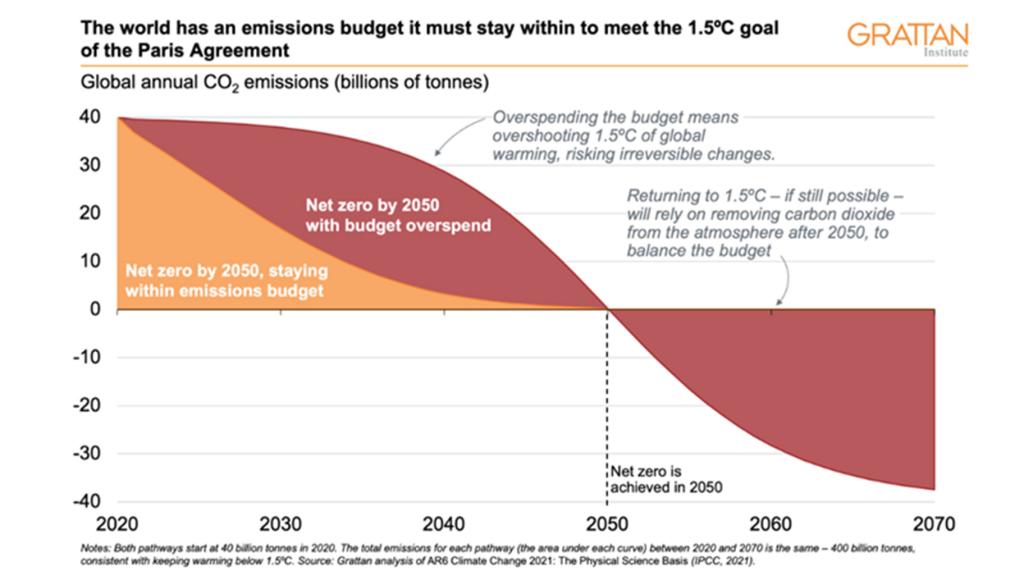

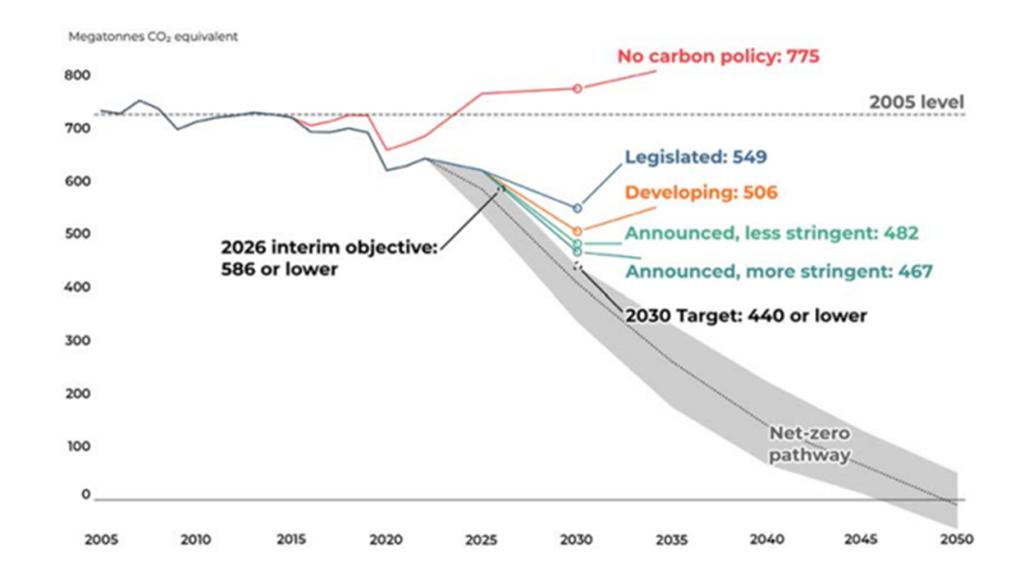

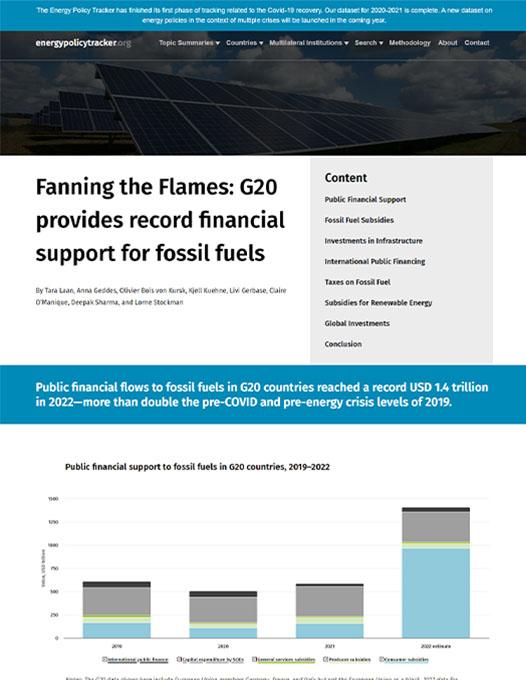

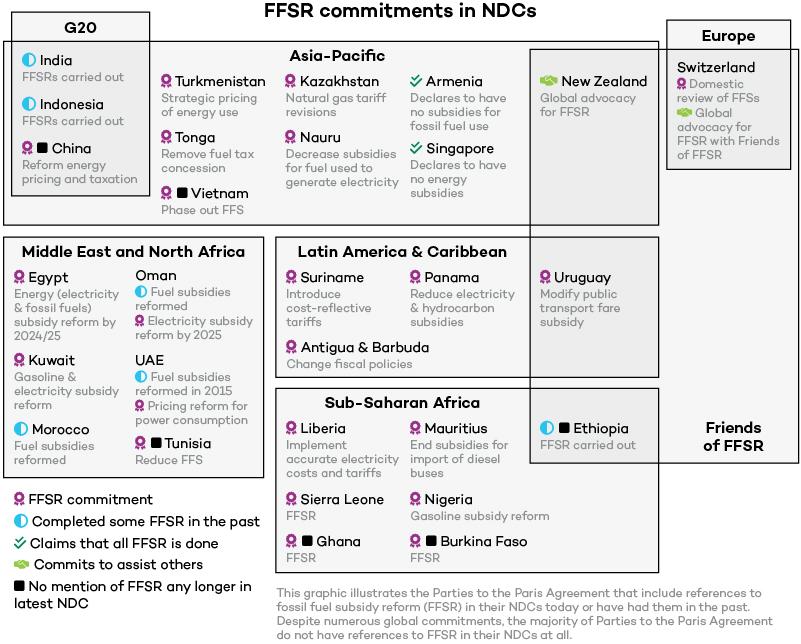

The 10 demands from the LCOY about sustainable systems cover everything from low-carbon energy to climate finance. Focusing on themes of carbon pricing, fossil fuel subsidies, and the need for a climate finance taxonomy, the participants want to see provincial and federal governments divesting from fossil fuels while at the same time investing in sustainable alternatives that align with the warming target of 1.5°C outlined in the Paris Agreement. They acknowledge Canada’s strengths and weaknesses regarding low-carbon energy. The prevalence of low-carbon electricity throughout the country is a strength; however, transportation is highlighted as an area that needs significant improvement. The authors also remind us that even non-carbon-emitting energy sources can have other environmental drawbacks that should also be accounted for. The list also has a section on sustainable cities, where the primary areas of concern are the importance of protecting urban green space and the need to transition away from automobile dependency. The common thread between both of these is intentional urban planning that encourages alternative modes of transportation, like cycling and public transit, and the incorporation of green space into urban areas.

Prioritizing Our Planet and a Focus on Food

In terms of the health of our planet overall, the youth authors’ statement featured 12 demands. Canada contains a unique richness of biodiversity as well as multiple anthropogenic factors that place this biodiversity at risk. While the authors feel Canada has generally been doing well in meeting commitments to the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, there is still significant room for improvement when it comes to protecting biodiversity. The authors promote the conservation of natural areas as a key priority, as well as using a diverse suite of metrics when measuring biodiversity and determining which areas need special protection. The three oceanic coastlines of Canada are facing plastic pollution and issues regarding sustainability in the fishing industry. Young people prioritize increased protections for the Arctic coast (which is at particular risk from oceanic warming) and greater transparency in the marine fishing industry on all coasts.

A topic that many Canadians are focusing on—food and agriculture—is highlighted in the youth statement, which encourages policy-makers to consider regionally specific strategies that account for the diversity of biomes across the country. The document also urges the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions at all points along the food production chain, from agriculture to household food waste. Reducing excess emissions produced by animal agriculture was also highlighted, in addition to offering more education about sustainable diets for regional populations. They also demand the implementation of easily accessible municipal composting programs so households can better manage their food waste.

Political, Societal, and Governance Practices

While there were only two demands covering political, societal, and governance practices, the importance of these points highlights the eagerness and ambition of young leaders who want to take action to improve Canada and the world. There is a call for greater accountability from the federal government on hitting climate-related targets and greater inclusion of Indigenous Peoples at all levels of decision making. This takes into consideration climate justice, as Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately harmed by climate change.

Finally, the demands serve as a reminder that Canadian youth are highly motivated when it comes to climate politics and are participating in many different ways, from volunteering during elections to sitting on advisory committees. The contents of this policy document speak for themselves—Canadian youth are knowledgeable when it comes to sustainability policy. All governments need to do is open a seat at the table, and Canadian youth will contribute their incredible passion and knowledge to policy at all levels. Specifically, the authors demand greater inclusion of Indigenous youth, meaningful opportunities for youth co-leadership, and that youth stakeholders who participate in meetings be provided with the same exclusive documents available to other stakeholders.

Themes for Our Future

The full list of demands for policy-makers created by the Canadian LCOY goes into greater depth into these points and delves beyond what is covered here. However, there are a few themes emerging as priorities for the Canadian youth involved in its development.

First is the importance of taking greenhouse gas emissions seriously across all sectors of the economy. Whether it be demands for divesting from fossil fuels in the climate finance sector, calls for reduced emissions in agriculture, or reduced automobile dependency, every focus area ultimately comes back to this one issue. Canadian youth name the limiting of fossil fuel emissions as a high priority.

Indigenous inclusion in decision making is at the heart of what Canadian youth want to see when it comes to impacting climate policy. Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change, and Canadian youth are taking notice, making clear how important it is that diverse voices are heard.

Finally, the report stresses the need to set up Canadians for success when it comes to living sustainably. This includes designing cities to reduce the necessity of car ownership, making food production more sustainable, and making it easier for everyday Canadians to avoid plastic waste. Canadian youth have identified how hard it is to live a sustainable lifestyle without the help of strong, sustainable policies being implemented at all levels. Policy-makers should take note of this concern among the next generation of leaders.

Canadian youth have a lot to say when it comes to climate policy in Canada, and they have the knowledge to back it up. Make sure to check out the LCOY 2023 Policy Document whether you are a decision maker, a climate expert, or even just a supporter of youth leaders.

If you are a Canadian youth who wants to learn more about policy and its impact or want to prepare for a career in sustainable development, IISD Next hosts a Campus Workshop Series on Sustainability each academic year. Sign up to learn when registration opens and to learn more about the series.