It began and ended with two new cabinets and two new words: climate change.

They were added to the title of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s first Minister of the Environment and Climate Change in 2015; and taken away from the new title for Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s first Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks in 2018.

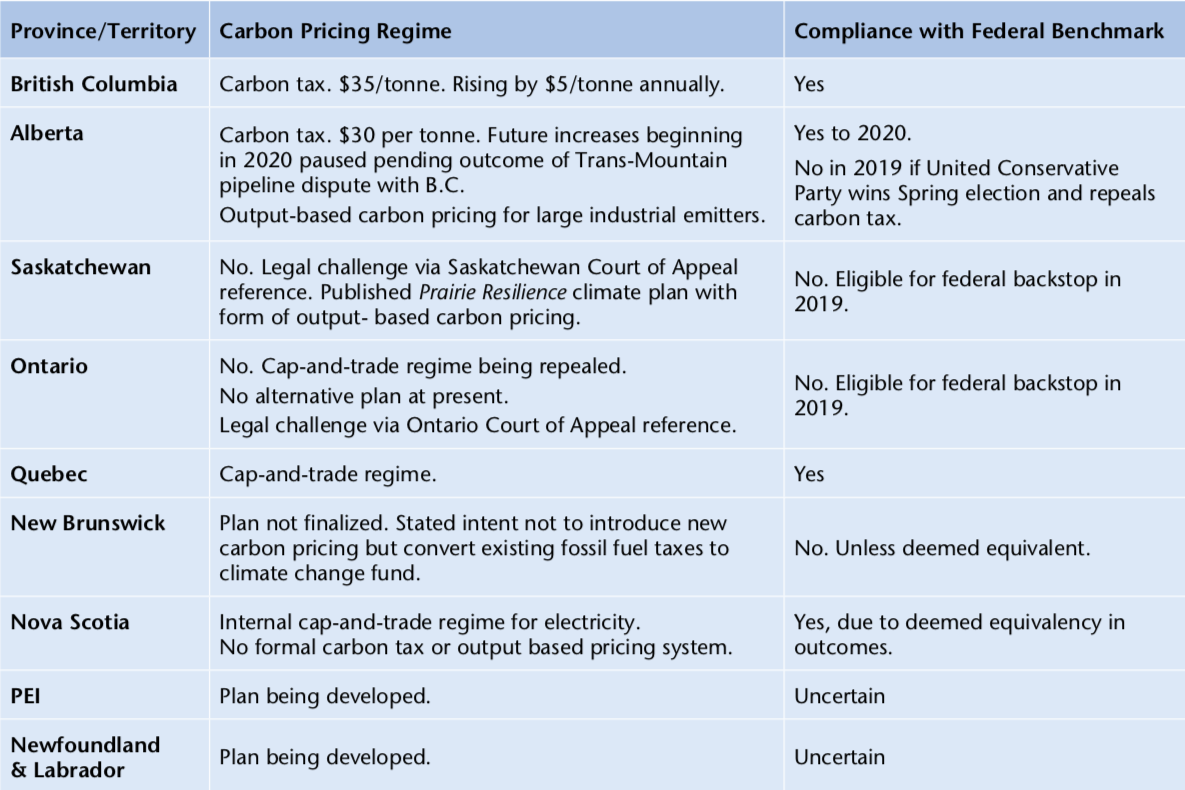

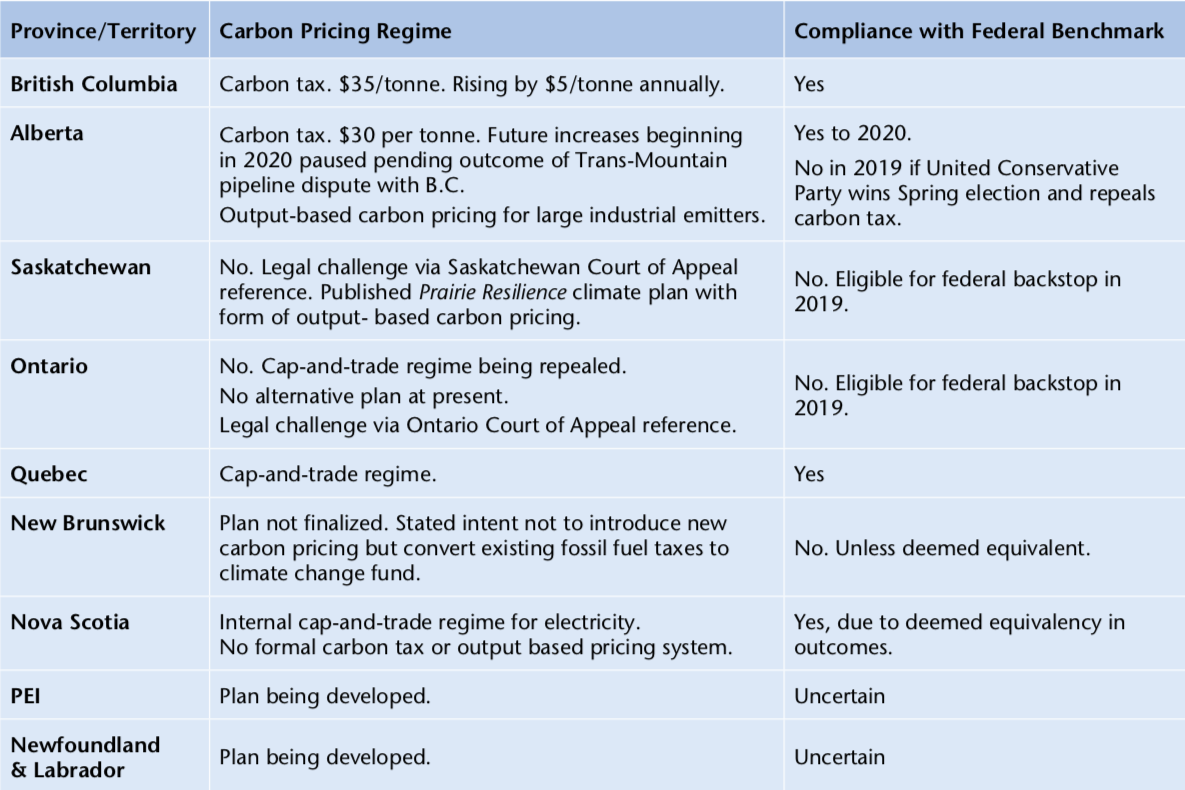

Those two cabinet changes mark the high- and low-water marks of climate change progress in Canada. With the first, the Trudeau government set about creating the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF) in December 2016. With the second, the Ford Progressive Conservative government repealed its cap-and-trade system and commenced a legal challenge to Ottawa’s plan to require provinces to implement carbon pricing regimes by 2019.

In just over two years, Canada has swung from a seeming inevitability on climate action with carbon pricing to a pitched political battle between Liberals and Conservatives, some provinces and Ottawa, challenging the very notion of carbon and climate action at all. Climate policy has reached a crossroads in Canada. Next year’s federal election looks now as the deciding event.

Despite the federal Liberal government’s avowed commitment to global and Canadian climate action under the slogan “Canada is Back”, the terrain for what became the PCF was tilled by “the two Stephens”: Harper and Dion. The 2008 federal election put paid to the notion of a carbon tax to reduce emissions. Then Liberal leader Stéphane Dion promoted his Green Shift carbon tax. Prime Minister Stephen Harper castigated it as a “tax on everything”, winning an increased minority government.

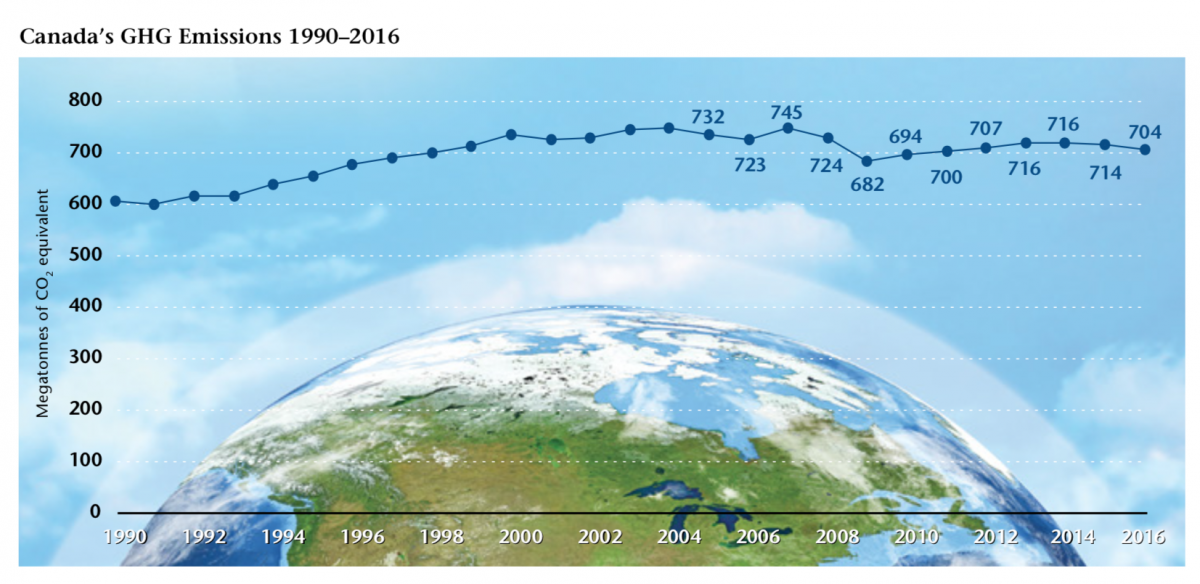

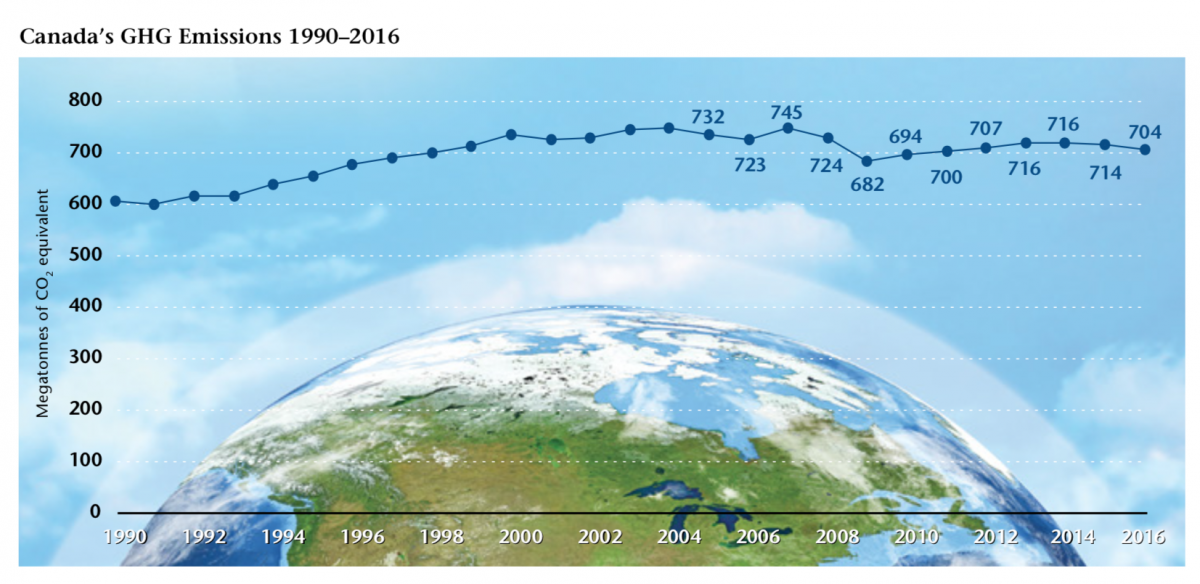

From that moment on, federal Conservatives became unalterably opposed to formal carbon pricing as a tool to reduce emissions, despite their own, soon-to-be-discarded cap-and-trade plan known as Turning the Corner. A slow, sector-by-sector regulatory approach was adopted instead. But the high-emitting oil and gas sector was consistently left out and Canada’s emissions rose until the 2008-09 recession caused them to drop, before rising again.

But if Harper effectively poisoned the political well on using a carbon tax, he bequeathed a poisoned chalice to both his own party and the Trudeau government: his Paris 2030 targets. By setting yet another ambitious GHG reduction target of 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, he just as effectively boxed-in future government action. Thinking this target would be politically bullet-proof from their Conservative opponents, the Liberals adopted it with alacrity in 2015. Andrew Scheer, the new Conservative party leader, then drank from it earlier this year with a public commitment to reach the Paris target but without a carbon tax.

Yet, this target is proving just as resistant to actual achievement as every other Canadian climate target from Kyoto onwards. Now owning it, the Liberals are criticized for instituting a modest carbon tax to help achieve it (it is either too much or not enough, say the same critics). Meanwhile, the Conservative position will be extremely difficult, if not outright impossible, to accomplish with a regulatory approach alone.

The basis, then, for sound climate public policy in this pre-election year is increasingly looking like a re-run of the 2008 campaign.

The Trudeau government’s initiative to knit together a pan-Canadian climate approach was based on the realism of federalism and the state of climate play when he took office. Under the Harper government, provinces had been the leaders in climate action, from British Columbia legislating the country’s first-ever carbon tax to Ontario closing down its coal-fired electricity plants to Quebec bringing in cap-and-trade. Any national policy had to realistically account. Here’s a thought experiment: if the Liberals took office today determined to bring in a national climate policy, would they bring in their current PCF plan?

The answer is very likely “no”. With dimming provincial support for climate action, it would be up to the federal government to impose a uniform carbon price and the elements of a pan-Canadian climate plan. In less than two years, Canada has moved from a provincially-led, federally-backstopped climate policy to one that looks more and more ‘federally-led, provincially-backstopped’.

In that vein, the Ford government’s withdrawal from the climate sphere can be seen as either a brake or an accelerator to a truly pan-Canadian climate policy for the country. Carbon pricing opponents are framing it as unstoppable momentum to ending the “Trudeau carbon tax”—the brake. Seen another way, it actually creates an opportunity for the federal government to re-cast its pan-Canadian climate policy and bring about the carbon price uniformity and certainty sought in the PCF—an accelerator. The tool to do so: revenue recycling to people.

There is today a window to implement a truly national PCF that fits more directly into a federally-mandated carbon and climate policy. One that does not focus on price stringency to achieve environmental outcomes. Here are the elements that could make it up:

First, leave Quebec alone to implement its cap-and-trade system with California under the Western Climate Initiative. There is no movement currently in Quebec to withdraw from carbon pricing or climate action. As this is an international agreement, Ottawa should not sunder it.

Second, bring in a national carbon tax floor of $25 or $30 per tonne (or 5-7 cents per litre of gasoline) for all other provinces at once. Instead of just doing this for two provinces now and presumably Alberta later, apply it to all of them. Provinces could have a higher price if they so desired, but they could not have a lower price. This is higher than the current $20 per tonne price set for 2019 but not unduly so. A higher price would also incent more emissions reductions at the outset.

(A $30 per tonne “carbon price collar” was in fact recommended by the now-defunct National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy in 2010 as a competitiveness measure to allow Canada to move on climate action without getting too far ahead of the U.S.)

Third, keep that price flat until the 2022 review. Business is worried about escalating carbon prices and a “layering” of regulations on top of it, and this would give a pause to businesses’ benefit while NAFTA is settled with the United States.

Fourth, recycle all of the carbon tax revenue directly back to residents in each jurisdiction in the form of dividend or rebate cheques. Better still, do it for individuals, not households, to maximize the size and visibility of the dividend. For those provinces with revenue recycling systems already in place, they could have the choice of retaining their current system or withdrawing in favour of the federal government’s dividend cheques, which would actually be worth $200-$300 for each person. A four-person household could wind up receiving rebates totalling more than a thousand dollars.

Fifth, bring in output-based carbon pricing for large emitters as currently being implemented in Alberta, and planned for Saskatchewan and Manitoba. This system of industrial performance standards reduces the cost of carbon pricing for emitters by returning a portion of their payments in the form of a subsidy. This prevents carbon leakage and reduced production for trade-exposed sectors. The recent adjustments by the federal government to its proposed output-based system actually eased the cost burden even further on industry; smart recognition that industry needs more transition support to implement carbon pricing, even if the politics of doing so has left the Trudeau government open to largely specious charges of back-tracking on its carbon policy.

At one bold stroke, the federal government would take the policy responsibility to go with the political responsibility it has for all practical purposes already assumed for its carbon and climate approach. The effect of hundreds of dollars in rebate cheques going into peoples’ pockets is the best, and frankly, only way at this juncture to ease carbon pricing into place for all Canadians.

The federal government’s legal authority to tax and distribute is widely agreed. By having an equal carbon floor price across the country, all jurisdictions are being treated the same. A uniform carbon price for the country takes root. Since the effect of the legal challenge from Saskatchewan and Ontario is to curtail federal action period on climate, it can be seen as a necessary but limited assertion of federal authority in this important field.

The effect of this would be to impose a carbon price on the following provinces: Alberta (if there is a change in government), Saskatchewan, Ontario, New Brunswick, PEI, and Newfoundland and Labrador. The floor carbon price is modest enough not to create significant economic differentials between provinces. The flat rate ensures the political impact is equally modest as consumers and businesses are not hit with rising fuel bills each year. And, it requires governments to look at more politically-acceptable non-pricing measures to close the Paris gap.

Ottawa has lost control of the climate narrative in the country. 2018 is not 2015 or 2016 in terms of its political authority and willingness of provinces to collaborate on climate. Only a bold move will suffice to salvage it. But to bite the bullet on climate, it must water its wine too. A revised national carbon floor price with full revenue recycling cheques back to individuals does just that.

It still features key elements of the current PCF: carbon pricing, output-based industrial pricing, revenues kept in each jurisdiction, a 2022 review, and provincial flexibility to do more.

Next year—an election year—is likely to determine whether Canada will act as one on climate or reanimate the fragmented approach of the recent past. If elections matter, this next one promises to be consequential.

This op-ed first appeared in Policy Magazine on August 24, 2018.