Could a U.S.–China Trade War Lead to a New Wave of Land Grabs?

A trade war could force China to search for new frontiers to secure its soybean demand and protect its supply chains, leading to another wave of so-called “land grabs.”

A trade war is looming between the United States and China. President Donald Trump has proposed tariffs on over 1,000 Chinese imports.

***Français suit***

China has responded, saying it would impose duties on U.S. imports, including agricultural products. If they follow through, the resulting trade war would be disastrous—and not just for those two countries. What could it mean for global food security and the environment?

Let’s examine the case of soybeans, which China threatens to hit with a 25 per cent import tariff. Today, soybeans are a ubiquitous commodity in the global food chain. Seventy per cent of soy production goes to feed animals, particularly chickens, pigs and cows, as producers cater to the increased demand for meat from growing middle classes. The rest goes toward cooking oil, biodiesel, oleochemicals and other processed foods.

Agriculture and changes in land use already account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions—a new wave of investment in soybean production outside the U.S. will lead to still more clearing of land, making matters worse.

The United States is the largest producer and exporter of soybeans, while China is the largest importer, importing two thirds of all U.S. exports. China cannot meet its own soybean demand because of limited agricultural land and stagnant yields. And yet its appetite for soybeans is immense: China imports close to 100 million metric tonnes annually—equivalent to 10,000 shipping containers per day. So what might happen if soybean imports from the United States are disrupted?

Such a move could unleash a major disruption of world markets reminiscent of the runup to the 2008 food price crisis—when the prices of rice, wheat and corn nearly doubled over a two-year period.

Shifts in China’s soybean supply typically have major market consequences. In March of this year alone, China purchased a third more soybeans from Brazil than a year earlier, driving up Brazilian soybean prices. If China replaces U.S. soybean imports with imports from other countries, their prices will rise. On the flip side, the U.S. could end up with a huge surplus of soybeans, driving down domestic prices and/or leading to dumping on other markets.

Historically, this type of disruption has had long-term impacts on the agricultural sectors of affected countries: When the Nixon administration implemented an embargo on soybean exports in the early 1970s, Brazil and Argentina expanded their production to fill the gap, triggering a trend that continues today.

More recently, the 2008 food price crisis triggered a global land rush. Many food-importing countries lost faith in the ability of world markets to reliably provide for their populations, and foreign and domestic investors acquired large tracts of farmland across Africa and Asia as a hedge against future uncertainty. A U.S.–China trade war could revive this unfortunate trend. China could be forced to search for new frontiers to secure its soybean demand and protect its supply chains, leading to another wave of so-called “land grabs.”

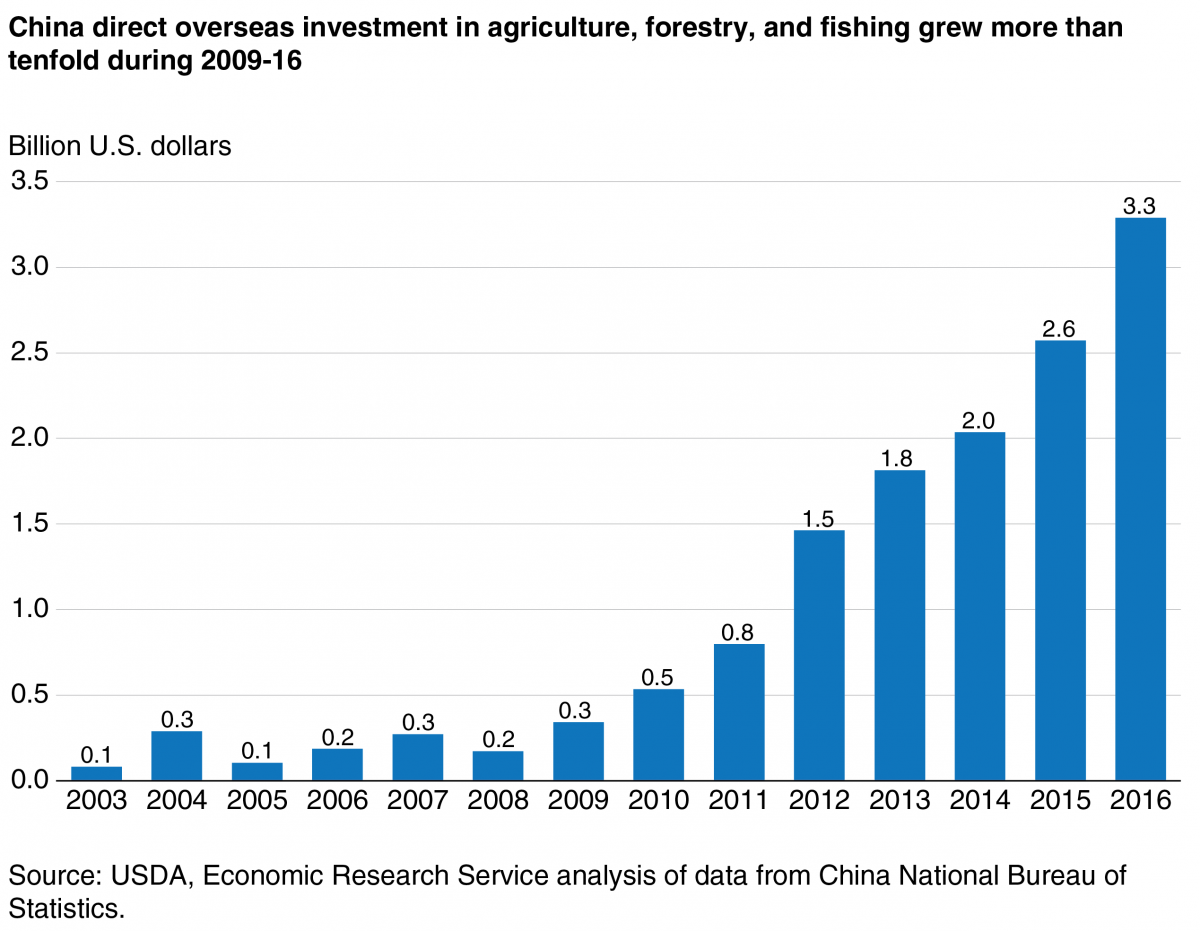

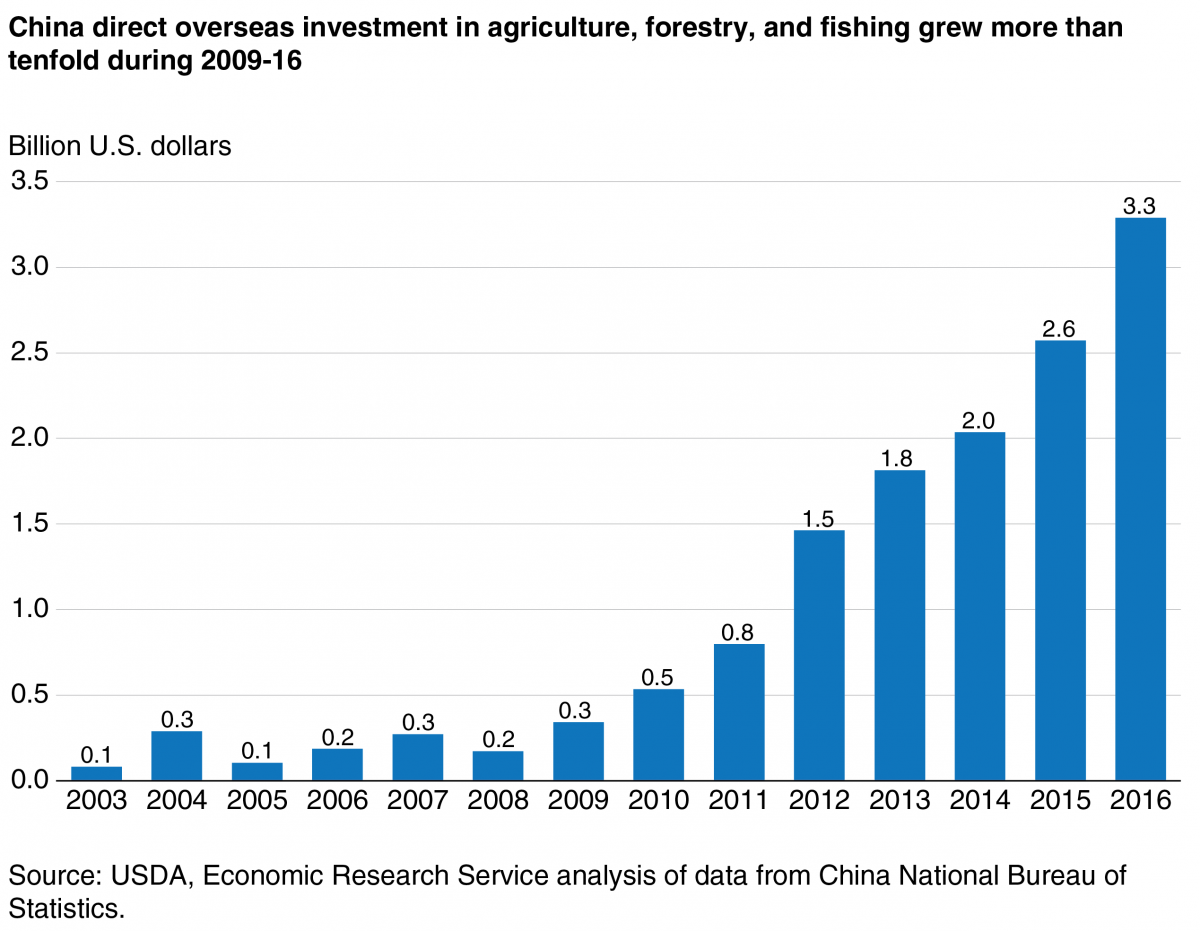

Indeed, China’s agricultural investments abroad have been growing steadily over the past decade, from USD 300 million in 2009 to USD 3.3 billion in 2016, most of it going to Asia (see chart below). Meanwhile, the Chinese chemicals giant ChemChina recently bought Swiss agrochemical giant Syngenta for CHF 43 billion.

If China and other countries expand global soybean production, that could exacerbate the negative environmental impacts of the global soy footprint. Soybeans are already a driver of deforestation in Brazil and Argentina. The area of land in South America devoted to soy more than tripled, from 17 million to 58 million hectares, between 1990 and 2015, mainly on land converted from natural ecosystems (FAOSTAT). Agriculture and changes in land use already account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions—a new wave of investment in soybean production outside the U.S. will lead to still more clearing of land, making matters worse.

What can be done to head off disaster? First and foremost, a trade war must be averted at all costs. But there are other opportunities for action. Governments in Africa and Asia could now act on the lessons learned from the last wave of foreign land investment. Reforms have already been introduced in many countries to reform corrupt or insider-driven business practices, and better represent the interests of people and the environment. New land laws in Mali and Benin provide a durable solution to land tenure insecurity in rural communities. Laos introduced a temporary moratorium on land investments in order to conduct a comprehensive inventory of deals and improve the legal framework for foreign investment.

China cannot meet its own soybean demand because of limited agricultural land and stagnant yields

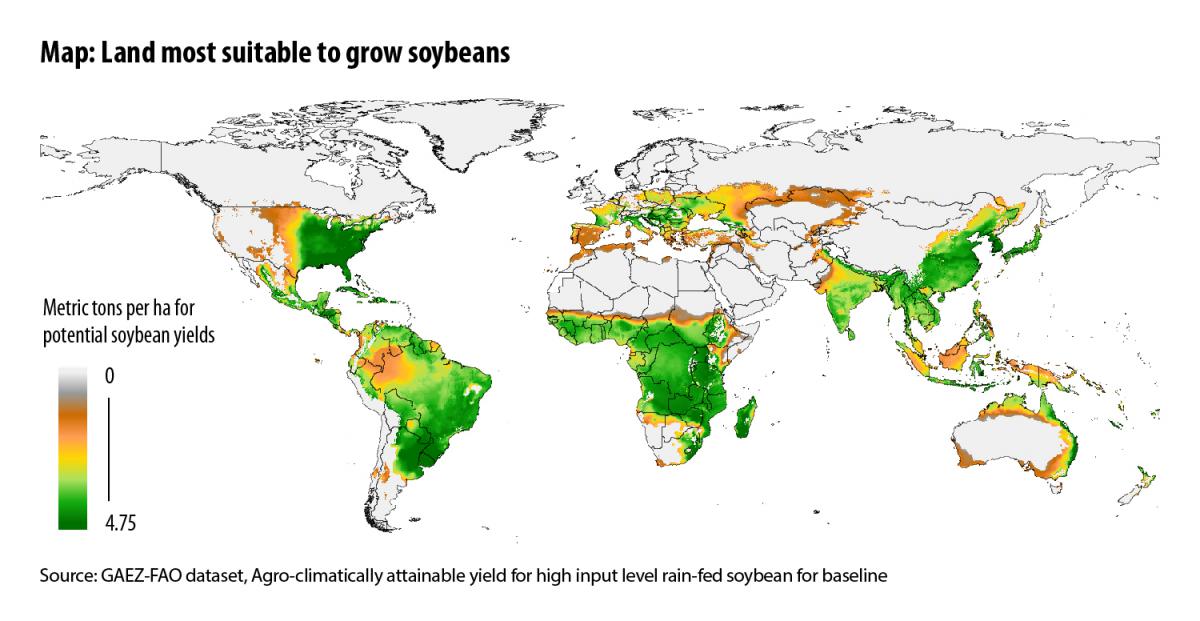

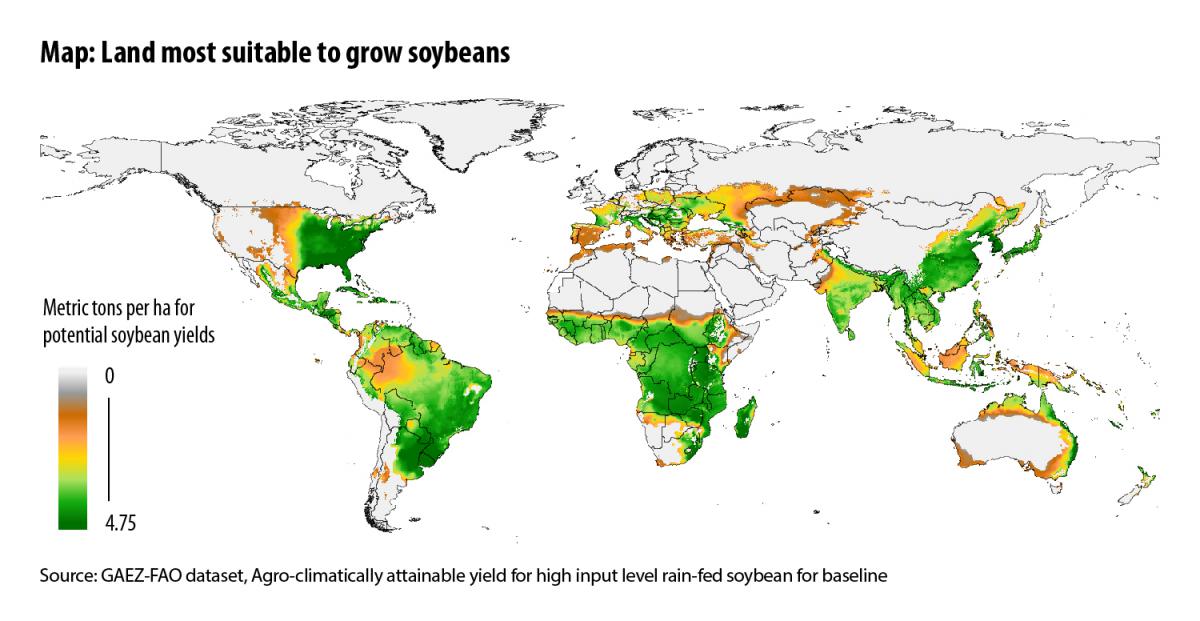

Indeed, as shown on the map below, several African countries could become the new frontier for soybean expansion, in particular in Central and Eastern Africa. This means that the new East African Community (EAC) model contract for farmland investments is highly relevant, as it strengthens the processes for managing environmental and social impacts, and for ensuring that women’s land rights are protected.

Finally, the threats posed by today’s trade tensions offer an opportunity to rethink current production and consumption patterns and reform food systems. For the sake of the environment and for global food security, meat and dairy consumption must be reduced in countries where the consumption is too high: essentially all industrialized countries. In addition, sustainable agricultural production methods such as reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and promoting the use of animal manure as natural fertilizer must be adopted. By taking such proactive steps, the world can build sustainable, more resilient food systems that can weather both the trade and climate upheavals.

Carin Smaller is Advisor on Agriculture and Investment at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

David Laborde is Senior Research Fellow in the Markets, Trade and Institutions Division and the Team Leader on Macroeconomics and Trade for the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Une guerre commerciale entre la Chine et les États-Unis pourrait-elle conduire à une nouvelle vague d'accaparement de terres agricoles ?

Une guerre commerciale se profile entre les États-Unis et la Chine. Le président Donald Trump a proposé d'instaurer des droits de douane sur plus de 1 000 produits importés de Chine.

La Chine a répliqué en annonçant qu'elle imposerait des taxes sur les importations américaines, dont les produits agricoles. S'ils poursuivent sur cette voie, la guerre commerciale qui en résulterait serait une catastrophe — et pas seulement pour ces deux pays. Quel serait l'impact sur la sécurité alimentaire et environnementale mondiale ?

Prenons l'exemple du soja, auquel la Chine menace d'appliquer une taxe d'importation de 25 %. Aujourd'hui, le soja est un produit omniprésent dans la chaîne alimentaire mondiale. Soixante-dix pour cent de la production de soja est destinée à l'alimentation des animaux, notamment des poulets, des porcs et des vaches, les producteurs répondant à la demande croissante de viande de la part des classes moyennes toujours plus nombreuses. Le reste est destiné à l'huile de cuisson, au biodiesel, aux produits oléochimiques et à d'autres produits alimentaires transformés.

L'agriculture et les changements dans l'utilisation des terres sont déjà à l'origine d'environ un quart des émissions mondiales de gaz à effet de serre - une nouvelle vague d'investissements dans la production de soja hors des États-Unis entraînera encore plus de défrichement, aggravant la situation.

Les États-Unis sont les plus grands producteurs et exportateurs de soja, tandis que la Chine est le plus grand importateur, important les deux tiers de l'ensemble des exportations américaines. La Chine ne peut pas répondre à sa propre demande en soja, ses terres agricoles étant limitées et ses rendements stagnants. Et pourtant, son appétit pour le soja est énorme : la Chine importe près de 100 millions de tonnes métriques par an, soit l'équivalent de 10 000 conteneurs par jour. Alors, que se passerait-il si les importations de soja en provenance des États-Unis étaient perturbées ?

Une telle mesure pourrait déclencher une perturbation majeure sur les marchés mondiaux, rappelant la période précédant la crise du prix des produits alimentaires de 2008, lorsque les prix du riz, du blé et du maïs ont presque doublé en l'espace de deux ans.

Les changements dans l'approvisionnement du soja en Chine ont généralement des conséquences majeures sur le marché. Rien qu'en mars cette année, la Chine a acheté un tiers de soja de plus au Brésil que l'année précédente, faisant grimper les prix du soja brésilien. Si la Chine remplace les importations américaines de soja par des importations d'autres pays, leurs prix augmenteront. D'un autre côté, les États-Unis pourraient se retrouver avec un énorme surplus de soja, ce qui ferait baisser les prix sur le marché intérieur et/ou entraînerait du dumping sur d'autres marchés.

Historiquement, ce type de perturbation a eu des impacts à long terme sur les secteurs agricoles des pays concernés : lorsque l'administration Nixon a imposé un embargo sur les exportations de soja au début des années 1970, le Brésil et l'Argentine ont augmenté leur production pour combler l'écart, déclenchant une tendance qui se poursuit aujourd'hui.

Plus récemment, la crise des prix des produits alimentaires de 2008 a déclenché une ruée mondiale sur les terres. De nombreux pays importateurs de produits alimentaires ont perdu leur confiance dans la capacité des marchés mondiaux à approvisionner leurs populations de manière fiable, et les investisseurs étrangers et nationaux ont acquis de vastes surfaces de terres agricoles en Afrique et en Asie pour se prémunir contre l'incertitude future. Une guerre commerciale entre les États-Unis et la Chine pourrait relancer cette tendance déplorable. La Chine pourrait être contrainte de chercher de nouvelles frontières pour assurer sa demande en soja et protéger ses chaînes d'approvisionnement, ce qui conduirait à une autre vague de ce que l'on appelle communément « accaparements de terre ».

En effet, les investissements agricoles de la Chine à l'étranger ont augmenté de façon régulière au cours de la dernière décennie, passant de 300 millions en 2009 à 3,3 milliards de dollars américains en 2016, dont la plus grande partie est destinée à l'Asie (voir graphique ci-dessous). Entre-temps, le géant chinois de l'industrie chimique ChemChina a récemment racheté le géant suisse de l'agrochimie Syngenta pour 43 milliards de francs suisses.

.

Source : USDA, analyse de données du service de recherche économique du bureau national des statistiques chinois.

Si la Chine et d'autres pays accroissent la production mondiale de soja, les impacts négatifs de l'empreinte mondiale du soja sur l'environnement pourraient s'aggraver. Le soja est déjà un facteur de déforestation au Brésil et en Argentine. La surface de terres consacrées au soja en Amérique du Sud a plus que triplé, passant de 17 millions à 58 millions d'hectares entre 1990 et 2015, principalement sur des terres converties à partir d'écosystèmes naturels (FAOSTAT). L'agriculture et les changements dans l'utilisation des terres sont déjà à l'origine d'environ un quart des émissions mondiales de gaz à effet de serre - une nouvelle vague d'investissement dans la production de soja hors des États-Unis entraînera encore plus de défrichement, aggravant la situation.

Que peut-on faire pour éviter la catastrophe ? Tout d'abord, une guerre commerciale doit être évitée à tout prix. Et il existe d'autres possibilités d'action. Les gouvernements d'Afrique et d'Asie peuvent désormais tirer les leçons de la dernière vague d'investissements fonciers étrangers. Des réformes ont déjà été instaurées dans de nombreux pays pour réformer les pratiques commerciales corrompues ou menées par des initiés. Ces réformes visent à mieux préserver les intérêts des personnes et de l'environnement. De nouvelles lois foncières au Mali et au Bénin apportent une solution durable à l'insécurité du régime foncier dans les communautés rurales. Le Laos a instauré un moratoire temporaire sur les investissements fonciers afin de dresser un inventaire exhaustif des transactions et d'améliorer le cadre juridique de l'investissement étranger.

La Chine ne peut pas répondre à sa propre demande en soja, ses terres agricoles étant limitées et ses rendements stagnants

En effet, comme le montre la carte ci-dessous, plusieurs pays africains pourraient devenir la nouvelle frontière pour le développement du soja, en particulier en Afrique centrale et orientale. Cela signifie que le nouveau Contrat type de la Communauté de l'Afrique de l'Est (CAE) pour les investissements en terres agricoles est très pertinent, dans la mesure où il renforce les processus de gestion des impacts environnementaux et sociaux et garantit que les droits fonciers des femmes sont protégés.

Source : ensemble de données de GAEZ-FAO, production atteignable agro-climatiquement pour du soja à haut niveau d'entrée arrosé par la pluie pour point de comparaison

Enfin, les menaces que représentent les tensions commerciales en cours offrent l'occasion de repenser les schémas actuels de production et de consommation et de réformer les systèmes alimentaires. Dans l'intérêt de l'environnement et de la sécurité alimentaire mondiale, la consommation de viande et de produits laitiers doit être réduite dans les pays où elle est trop élevée : pratiquement tous les pays industrialisés. En outre, des méthodes de production agricole durables doivent être adoptées, comme la réduction de l'utilisation d'engrais chimiques et l'encouragement à utiliser du fumier animal comme engrais naturel. En prenant de telles mesures proactives, le monde peut élaborer des systèmes alimentaires durables et plus résilients capables de résister aux bouleversements tant commerciaux que climatiques.

Carin Smaller est conseillère en agriculture et en investissement à l'Institut international du développement durable (IIDD).

David Laborde est chercheur principal à la Division des marchés, du commerce et des institutions et chef d'équipe sur la macroéconomie et le commerce pour l'Institut international de recherche sur les politiques alimentaires (IFPRI).