Leveraging the Linkages: How human rights data can advance SDG monitoring

To create opportunities for synergies between the "leave no one behind" principle and the "realize human rights for all" principle in implementation and improved monitoring, there is a need to properly leverage data and legal mechanisms.

The 2030 Agenda principle to “leave no one behind” is closely tied to another principle: to realize human rights for all. By properly leveraging data and legal mechanisms, this close relationship creates opportunities for synergies in implementation and improved monitoring.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other core human rights instruments identify basic human needs that must be respected for everyone, everywhere, always. Realizing and protecting human rights are prerequisites for progress on many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Data that has been collected to track developments in human rights implementation also yields important insights on progress toward related SDGs and can be used to complement other data sources for SDG monitoring. Moreover, legal overlaps could mean states can be held accountable for SDG implementation if they are linked to relevant human rights mechanisms where states have obligations under international human rights law.

Linkages Between Human Rights and the SDGs

Trends in human rights monitoring illuminate some of the benefits of linking data on human rights and the SDGs. According to a recent study conducted by Steven L. B. Jensen of the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR), key UN human rights bodies are increasingly referencing the SDGs in their recommendations. There is strong motivation for this shift: human rights monitoring mechanisms consider the 2030 Agenda an opportunity to further realize human rights for all. As SDG monitoring is bolstered and expands in frequency and reach, states will receive feedback from the international community as progress is continually assessed at every step of the way regarding not only the SDGs, but on human rights as well.

The connection between the SDGs and human rights is mutually reinforcing. As states have obligations under international human rights law, they can be held accountable for SDG implementation if these are linked to relevant human rights mechanisms. Linking up data on the SDGs, which are non-binding in nature, with data on international human rights and labour standards ensures SDG implementation increases the respect, protection, and fulfilment of human rights since these two concepts are deeply intertwined. Human rights linkages could also strengthen the ability of the annual UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) to ensure accountability from governments to their SDG commitments (Feiring & König-Reis, 2020).

International human rights mechanisms can advance the SDGs at the national level as well: their recommendations can help identify priority areas for individual countries’ SDG action plans, indicate the marginalized groups that require additional support, and suggest concrete measures to combat exclusion and discrimination.

Scope of Human Rights Data for SDG Monitoring

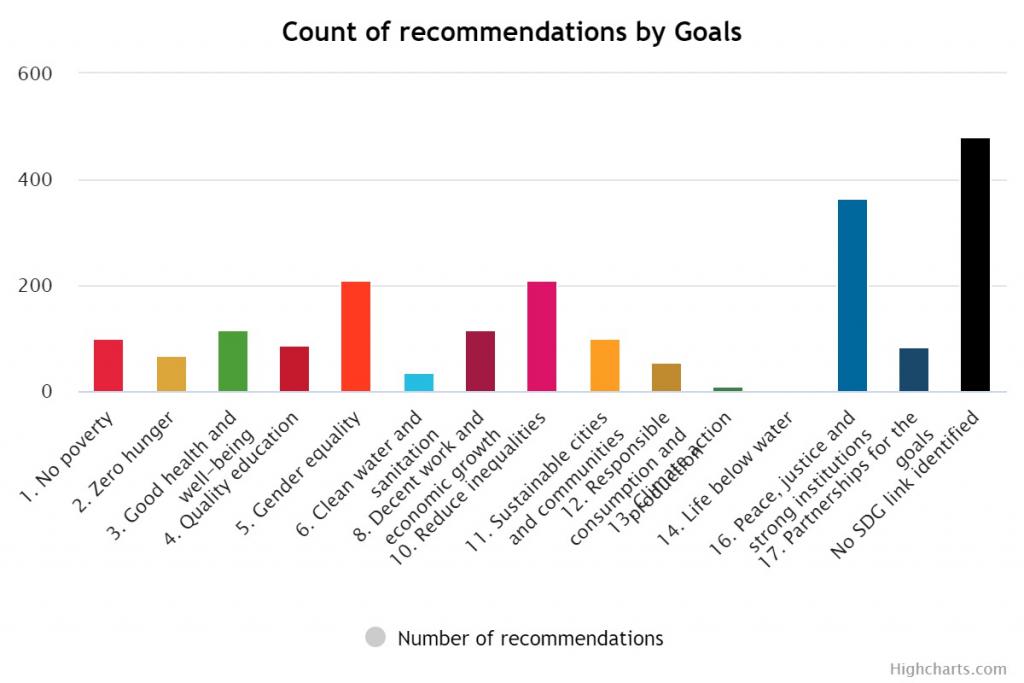

The SDG-Human Rights Data Explorer created by DIHR shows the extent of the opportunity to complement SDG monitoring with human rights data. The online tool uses artificial intelligence to evaluate monitoring information from international human rights mechanisms and maps their recommendations and observations to relevant SDGs and targets. Users can explore how recommendations from human rights monitoring bodies, such as the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), relate to the implementation of each SDG and the 169 targets around the globe.

At present, the database allows users to explore 145,000 recommendations from 67 mechanisms across the international human rights system. Over half of these recommendations are directly linked to specific SDG targets, and therefore immediately relevant for national SDG implementation. (DIHR, n.d.). For example, following the third UPR cycle in 2018, it was recommended that Canada “continue to strengthen protection of the rights of Indigenous women and girls against violence, in particular by systematically conducting investigations and ensuring the collection and dissemination of data on violence against Indigenous women.” The tool linked this recommendation to SDG targets 17.18 (capacity building for disaggregated data) and 5.2 (end all forms of violence against women and girls). Although target 17.18 is aimed at developing countries, the need to increase Canada’s data collection capacity on the issues faced by Indigenous Peoples, especially women, is emphasized.

For any country, knowing which SDG targets matter from a human rights perspective can boost political momentum for increased action.

A second tool developed by DIHR, The Human Rights Guide to the Sustainable Development Goals, allows users to determine which international human rights mechanisms have direct applications for each of the SDG targets. A simple example is to look at SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and contrast it with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). In total, five articles within the text are connected to six different SDG targets only relating to SDG 11. The data organized by this tool is immense and shows the strong connection between international human rights tools and the SDGs, considering more than 92% of the 169 SDG targets have a direct link to international human rights mechanisms, labour standards, and environmental agreements.

A Look at Canada’s Human Rights Recommendations

The SDG-Human Rights Data Explorer developed by the DIHR maps 145,000 human rights recommendations from 67 international human rights instruments to the SDGs. A search on recommendations addressing Canada shows that human rights issues in Canada most often relate to SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), and SDG 5 (gender equality).

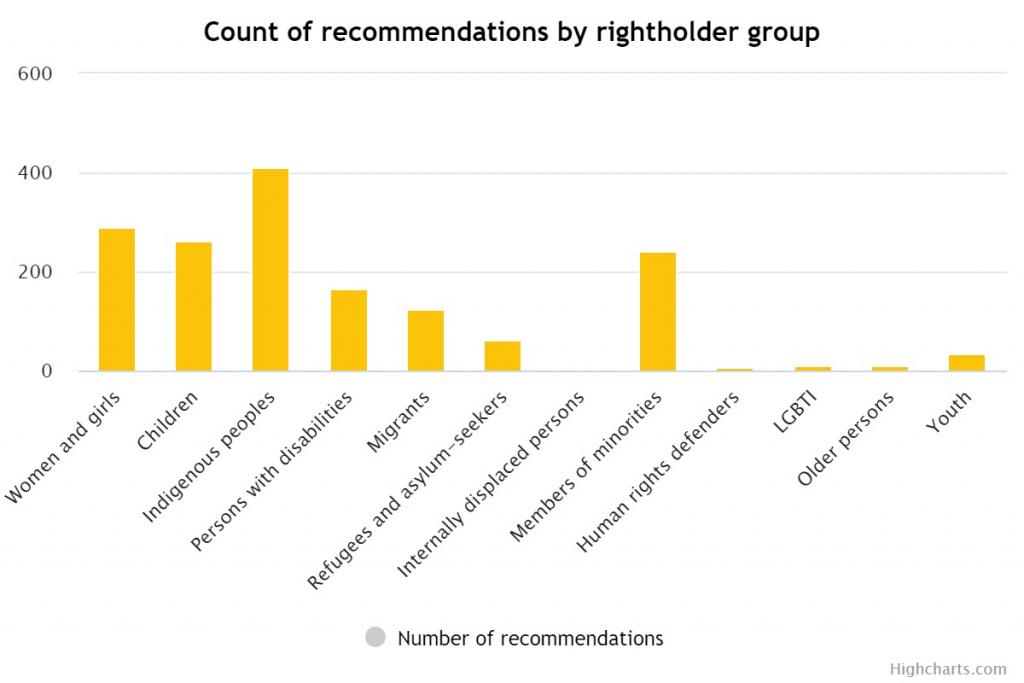

The database also allows searching for recommendations that relate to specific rightholder groups. For Canada, human rights recommendations most often address Indigenous Peoples, women and girls, and children. This can be used as an indication of the groups most affected by human rights issues in Canada.

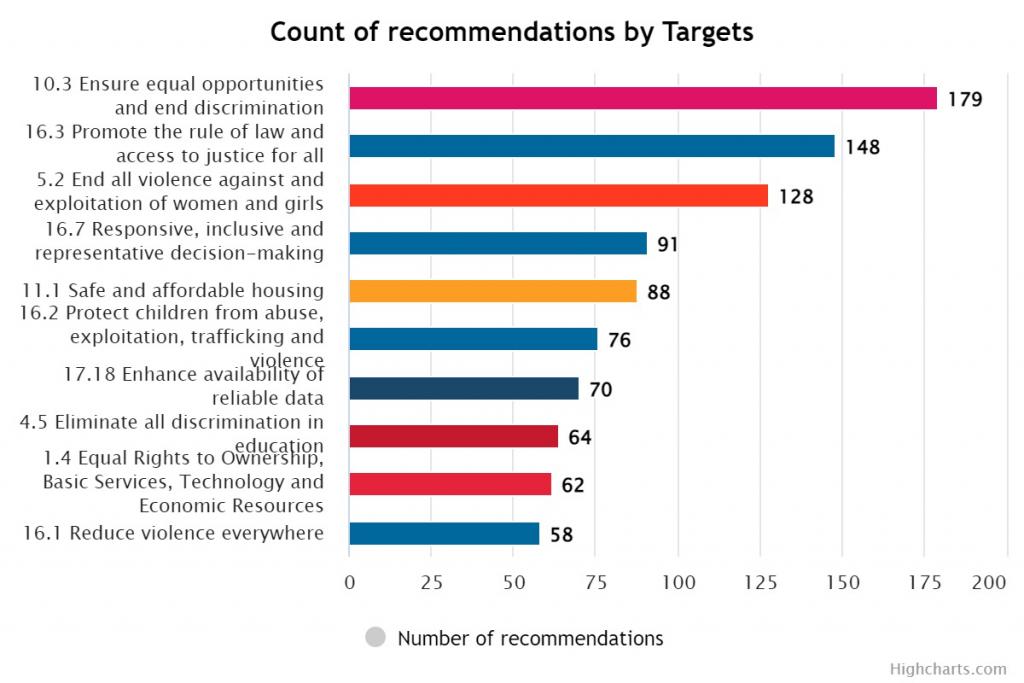

Digging deeper, a search focusing on recommendations relating to the human rights of Indigenous Peoples reveals the SDG targets most often addressed relate to:

- SDG target 10.3 (ensure equal opportunities and end discrimination)

- SDG target 5.2 (end all forms of violence against women and girls)

- SDG target 16.7 (responsive, inclusive, and representative decision-making)

- SDG target 16.3 (promote the rule of law and access to justice for all).

This initial analysis facilitated by the DIHR tools reveals a strong link between safeguarding human rights for Indigenous Peoples, particularly Indigenous women and children, and progress on SDGs 5, 10, and 16 in Canada. Addressing the human rights obligations relating to discrimination of Indigenous Peoples and violence against Indigenous women and girls, would directly impact Canada’s performance on these SDGs.

Taking a wider perspective, data on human rights recommendations underline the importance for Canada to address its colonial legacy. Reconciliation could be one of the most effective ways for Canada to make progress on many SDGs. Analyzing the content of the recommendations identified through the SDG-Human Rights Data Explorer provides insights into the need for SDG planning, implementation, and measurement to reflect the dimensions of reconciliation; these have clear impacts on Canada’s progress toward the SDGs.

The Role of National Human Rights Institutions

For any country, knowing which SDG targets matter from a human rights perspective can boost political momentum for increased action. It can also illuminate related aspects that should be monitored during implementation, as demonstrated in the case study above. In practice, this means building on the existing monitoring mandates of National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) to highlight SDG links in their work and to utilize the human rights monitoring mechanisms as an avenue to also review progress on the SDGs (Feiring & König-Reis, 2020).

Nearly 50% of existing SDG indicators produce data that is directly relevant to the monitoring of human rights instruments. NHRIs are sure to find significant benefits from engaging with the SDG–human rights relationship.

Integrating Human Rights Data in SDG Monitoring

An obvious recommendation arising from this discussion is to encourage closer collaboration between NHRIs and national statistics offices in SDG monitoring. But this is not a simple task.

Much of the data collected by NHRIs stem from complaints about human rights violations and the investigations and legal pursuits that may follow. Such data are sensitive, and careful processing is needed to publish them safely. Interpreting these data may be difficult as they often refer to specific groups or situations, making analysis and generalization tricky.

Nonetheless, examples from other countries suggest the effort is worthwhile. For example, Feiring showed a set of SDG targets addressing discriminatory legal frameworks and policies, inclusion, and policy coherence—SDG target 5.c, SDG target 10.2, SDG target 10.3, SDG target 10.4, SDG target 16.b, and SDG target 17.14—can all be measured by a single indicator on the number of countries that have ratified and implemented international conventions on equality and non-discrimination.

International collaboration can be another way to move forward. In Europe, the NHRIs of 40 countries have formed a network to enhance the promotion and protection of human rights across the region. Members have developed joint guides on topics such as measuring poverty reduction and advancing SDG 16 and benefit from frequent exchanges on evolving practices.

Finally, the Government of Canada could establish a process or body dedicated to measuring reconciliation progress in the context of the SDGs. Such an initiative would bring together the data experts of Statistics Canada, the human rights experts of Canada’s Commission on Human Rights, and most importantly the Indigenous Peoples whose rights must be established and protected to make progress on key SDGs in Canada. Such an initiative would establish accountability around the Government’s commitment to prioritize reconciliation and, with some investment, provide an appropriate framework to measure progress toward this goal.