WTO Debate on Future of “Differentiation” Highlights Challenges in Upcoming Negotiating Agenda

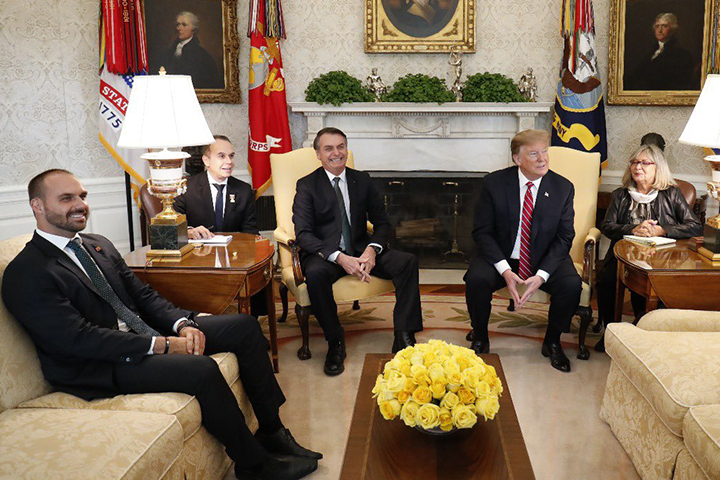

In March 2019, Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump announced Brazil will stop asking for certain types of treatment accorded to developing countries at the World Trade Organization.

On March 19, 2019, the presidents of the United States and Brazil made a landmark announcement: Brazil, South America’s largest economy, would move away from pursuing special and differential treatment (S&DT) in upcoming negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

This essentially means Brasilia will stop asking for certain types of treatment, such as different agricultural subsidy limits, or extra transition time to implement new disciplines, that can potentially be accorded to developing countries when negotiating new trade rules at the Geneva-based organization.

The statement from Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro adds another wrinkle to an intensified, long-running debate in trade circles over whether and how to reconsider the WTO practice of allowing members to “self-designate” as developing countries.

That designation has implications both for the application of global trade rules and for members’ respective “schedules” of concessions and commitments for goods and services. For example, in agriculture, developed and developing countries face different thresholds over the maximum level of trade-distorting domestic support they are allowed to provide.

In recent years, the United States has increasingly called for rethinking this practice of “self-designation,” arguing not only that it is outdated, but also damaging to the institution overall. They have repeatedly made their case at Geneva negotiating sessions and during the December 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

More recently, this past February the United States submitted a proposed General Council decision that, if approved, would limit certain WTO members from being eligible for special and differential treatment in future arrangements. While unlikely to be adopted, the U.S. proposal does indicate a significant intensification of the differentiation debate, with Washington calling for a sea change in how the organization’s 164 members approach the negotiation of new global trade rules.

According to the proposed draft decision, those WTO members not eligible for special and differential treatment would include those that are currently members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or trying to join; are part of the G20 coalition of advanced and emerging economies; are considered by the World Bank to be “high income” countries; or make up at least 0.5 percent of global merchandise trade. The range of members affected under this system would be significant: it would cover countries ranging from Argentina to China, India to Indonesia, with vastly different national and regional characteristics.

Notably, Brazil is beginning the process of trying to join the OECD, a move the Trump Administration says it supports.

The U.S. paired this proposal with a 45-page communication explaining its rationale. The rules-based trading system “is hardly monolithic,” the U.S. argues, citing the disparity between developed and developing countries over who is required to play by which rules. “The perpetuation of this construct has severely damaged the negotiating arm of the WTO by making every negotiation a negotiation about setting high standards for a few, and allowing vast flexibilities for the many.”

The U.S. also argues it is unfair to the organization’s poorest members to be lumped in the same category as larger economies that have better outcomes in indicators such as the Human Development Index or gross national income (GNI) per capita. Unlike other developing countries, least developed countries (LDCs) do not self-designate themselves as such, but are instead deemed as LDCs based on United Nations classification.

“Self-declaration also dilutes the benefit that the LDCs and other Members with specific needs tailored to the relevant discipline could enjoy if they were the only ones with the flexibility,” the U.S. says.

What this could mean for global trade talks

Coming as WTO members are actively pushing to conclude negotiations to discipline harmful fisheries subsidies before 2020, the U.S.’ call for ensuring these disciplines “apply to the world’s largest fishing nations, many of which are self-declared developing countries,” is already making waves in negotiating sessions, bringing an already contentious issue in the fisheries talks back to the forefront. A footnote in that U.S. document refers specifically to China, Indonesia, Peru, India, Vietnam, and the Philippines as ranking among the “top ten largest marine captures fisheries producers,” according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Meanwhile, agriculture negotiators are currently in the midst of a working group process to identify priority items for the next WTO ministerial conference, and the U.S. refers to an existing proposal by China and India which, the U.S. cautions, could complicate efforts at reforming domestic farm subsidies, given how it approaches the developed-developing country issue.

The U.S.’ proposed General Council decision has drawn pushback from several WTO members, and some have issued their own communication defending the practice of special and differential treatment as essential for ensuring “equity and fairness” and giving developing country members the space to address challenges that may not show up in economic indicators, but have real implications for people’s livelihoods. A joint communication from China, India, South Africa, Venezuela, Lao PDR, Bolivia, Kenya, and Cuba, dated February 26, counters the U.S. proposal on multiple grounds, though without referring to the U.S. by name.

“Recent attempts by some members to selectively employ certain economic and trade data to deny persistence of the divide between developing and developed members, and to demand the former to abide by absolute ‘reciprocity’ in the interest of ‘fairness’ are profoundly disingenuous,” they say. Furthermore, they note, the “development divide remains firmly entrenched” and must be acknowledged.

Along with arguing that the challenges faced by developing countries across different sectors and negotiating areas are more complex than what the US’ proposed category system allows, they also warn that the WTO is facing far different, and more serious, existential threats. This includes the impending collapse of its Appellate Body, given the U.S.’ repeated move to block the selection of new judges. They also refer to the “impasse” in the Doha Round trade talks and a worrisome rise in protectionist and unilateral trade actions.

As WTO members gear up for a packed 2019 calendar of multilateral negotiations on fisheries and agriculture, the Brazilian announcement issued from Washington has highlighted an issue that has long complicated global trade talks, but may now require even more nuanced thinking: that while the world has changed dramatically since the WTO replaced the previous General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) system, there is a fundamental difference in opinion on how this change has manifested itself, and how to reflect today’s and tomorrow’s realities and challenges when crafting new trade rules.

You might also be interested in

Global Dialogue on Border Carbon Adjustments

This report contributes to the global BCA discussion by summarizing country-level reports reflecting dialogues conducted in Brazil, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam.

Food Security: The Brazilian case

Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability: A landmark pact for trade and sustainability

The ACCTS pact, signed by Costa Rica, Iceland, New Zealand, and Switzerland, aligns trade and environmental policies, tackling fossil fuel subsidies, eco-labels, and green trade.

Addressing Carbon Leakage: A toolkit

As countries adopt ambitious climate policies, this toolkit examines strategies to prevent carbon leakage—when production and emissions shift to nations with weaker climate policies—and explores the trade-offs of each approach.