What Can You Afford in a Year Without Fuel Subsidies? Financing Development with the Reallocation of Indonesia’s Gasoline and Diesel Subsidies

For a long time, the international community has talked about the benefits that can be created by removing wasteful fossil-fuel subsidies and freeing up expenditure for more worthwhile things—but little analysis has looked at how this works out in practice.

In large part, this is because so few countries, including among the G-20, have implemented ambitious and successful reforms. It’s also because governments don’t tend to explicitly reallocate subsidy savings. Typically, all available revenue is simply pooled together and it can be challenging to associate a decrease in one area with an increase in another.

Indonesia’s recent experiences, however, offer some rare insights into this aspect of reform. In 2015, over US$ 15 billion were saved on fuel subsidies due a combination of price increases and low world oil prices. Thanks to fortunate timing, two budgets were drawn up: one, with full-cost subsidies; and one in the light of subsidy savings.

In collaboration with the Faculty of Economics and Business (P2EB) at the University of Gadjah Mada and the Asia Foundation, the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) delved into these budgets to identify, broadly—what might be afforded in a “year without subsidies”?

Where did the money go?

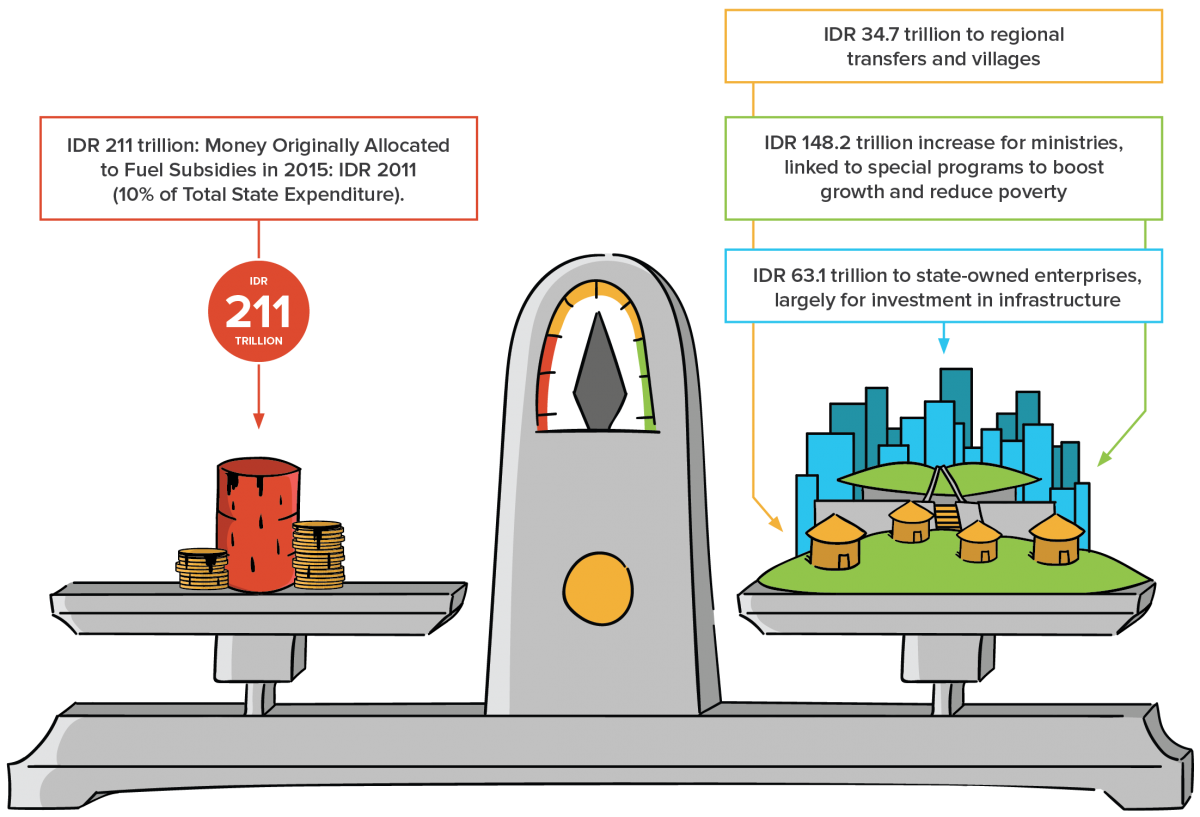

Indonesia’s original 2015 budget allocated around IDR 276 trillion (US$ 20.4 billion) to fossil fuel subsidies. Following retail price hikes and falling world oil prices, the government announced that it had eliminated the majority of gasoline and diesel subsidies by January 2015—even able to reduce retail prices slightly. The savings were equal to around IDR 211 trillion (US$ 15.6 billion), or 10 per cent of all government expenditure.

The analysis of budgetary documents revealed that funding for Ministries was increased by 23 per cent, from IDR 647 trillion to IDR 795 trillion (US$ 47 billion to US$ 59 billion), with the highest increases given to the Ministries of Agriculture (106 per cent), Transportation (45 per cent), Public Works and Housing (40 per cent) and Finance (37 per cent). The revised state budget also set out a number of “priority” programs, where it was expected that increased budgets would be used to achieve targets. This included programs related to education, health insurance, housing, clean water and transportation. One, for example, targeted the provision of housing for 60,000 poor households: another, clean water access for 10.3 million households.

Budgets for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were increased over 11-fold, from IDR 5 trillion to IDR 61 trillion (US$ 0.4 billion to US$ 4.5 billion). This capital injection was dedicated to investments in infrastructure in five main areas, under the themes of: infrastructure and connectivity; food sovereignty; economic autonomy; maritime; and security and defence. This included distributions to SOEs responsible for air services, sea transport, construction, housing, plantations, agriculture, fisheries, shipping, mining, rail, tourism and ports.

Finally, the revised budget saw a 2.8 per cent increase in transfers to regions and villages, from IDR 647 trillion to IDR 665 trillion (US$ 4.8 billion to US$ 4.9 billion). Some of these funds were tied to special projects determined by the government, including food sovereignty, traditional local markets, regional connectivity and health services; while some funds were to have their exact use determined by local authorities according to local needs.

These reallocations match up well with government statements that promised a shift from subsidizing “consumption” to making investments in people and infrastructure, as well as specific commitments related to individual areas of spending. Even where funding increases had no specific linkage with the subsidy policy—the increase in funding for villages, for example, was mandated by a law negotiated and passed in 2014—they were still made possible thanks to the fiscal space created by reform.

What was actually achieved?

It is difficult to determine the exact impacts of Indonesia’s reallocation because much of it takes the form of investments in people and infrastructure—and these will take years to yield their full benefits.

A preliminary analysis of the budgetary reallocation, however, found that it scored well in three areas. First, the budget was well aligned with the needs that have been identified in Indonesia’s medium-term development plan. Second, the reallocation was projected to boost the economy and jobs, as most of the sectors that received increased funds are associated with higher economic growth and rates of employment than fuel subsidies. Third, the budget was judged to be much less vulnerable to fiscal risk following the reform, largely because smaller fuel subsidies made the budget less prone to unpredictable variation as a result of world oil price fluctuations and currency changes.

The study was conducted before data was published on actual budgetary expenditure in 2015, so it remains to be seen how well planning has been followed through by implementation. In particular, it is known that revenue collection in 2015 was well below target, so it is possible that actual expenditure in certain areas may have been less ambitious than planned.

What Can We Learn From This?

The research team also conducted interviews to collect opinions from Indonesian civil society organizations (CSOs) that specialize in government expenditure and government officials. Generally, the reallocation was viewed positively: no interviewees considered the previous budget to have performed any better.

At a more discrete level, a range of discussion points emerged. Among CSOs, the effectiveness of the capital injection to SOEs was debated. Some argued the types of infrastructure would disproportionately benefit big companies and already-affluent regions, while others had concerns about how confident the public could be in the SOEs’ use of public funds.

Energy also emerged as a topic of debate. Some interviewees argued that large investments in roads would only encourage private transport use, while others noted the distinct lack of investment in clean energy, despite the need for Indonesia to transition away from carbon-intensive energy sources, particularly amid plans to significantly expand coal power generation.

Government officials noted the need to strengthen planning and coordination, so that government agencies have the capacity they need to make the most of additional funding.

Such views suggest that the reallocation of fuel subsidies—such as for electricity and liquefied petroleum gas, likely to see reforms in Indonesia in 2016 and 2017—needs to involve more public consultation and dissemination, more capacity building, and greater levels of transparency and accountability to track what has been achieved. In general, it is good not to simply pursue “reform” for its own sake, but to ask—what kind of reform do we want? How can it be made more or less sustainable? Doing so may be challenging, particularly in contexts where discussions can be easily politicised and go on to create further bottlenecks to reform. But it may also create benefits in the form of improved effectiveness, public acceptability and visibility of changes.

Indonesia’s experiences also underline the fact that any instance of subsidy reallocation can only be as good as the surrounding capacity for government to utilize resources well. Expectations should not be set so high that they fail to take into account what can be realistically achieved with existing administrative systems and policy tools. At the same time, cynicism about what is possible should not be used as an excuse to set ambition too low or to miss opportunities to improve the capacity to deliver efficiently.

The Big Picture

What can other countries learn from this? In many cases, it will depend on the share of subsidy savings that they are able to reallocate. In Indonesia, the government is legally obliged to deliver a deficit below 3% of GDP, so debt levels are relatively low. In turn, this means that subsidy savings can largely be reinvested. In other, countries where subsidies have driven unsustainable levels of debt, options for reallocation may be more constrained.

Nonetheless, Indonesia’s experiences in 2015 represent a tangible description of the opportunity cost of subsidies: all of the investments in improved welfare and economic growth that could be achieved for the same cost.

As world oil prices rise once more to levels of around US$ 50 per barrel, Indonesia—along with other countries around the world—may be eyeing its newly reformed gasoline and diesel prices and wondering how long it will be before public pressure mounts for subsidies to return once again. If anything, Indonesia’s experiences illustrate how desperately this must be avoided. Instead, social protection systems are needed that provide the vulnerable with targeted assistance during periods of global volatility—as well as robust pricing mechanisms that take away the political convenience of fuel subsidies. In the meantime, tracking and explaining the benefits of a “year without subsidies” is surely one of the most compelling strategies to shift attitudes about reform.

For more information about the findings discussed in this blog post, see the full study: Financing Development With Fossil Fuel Subsidies: The Reallocation Of Indonesia’s Gasoline And Diesel Subsidies In 2015.