Webinar Recap: National Oil Companies and Climate Change: Economic Challenges and Potential Responses

National oil companies (NOCs) are key players in the global oil and gas industry—they produce half of the world’s oil and gas, and invest 40 percent of capital into the sector. But policymakers and climate activists alike often overlook NOCs’ role in global efforts to address climate change. Omission of NOCs from climate strategies will significantly hamper governments’ attempts to meet global climate goals, and NOCs—along with the countries that depend on their revenues—could be left behind.

On 21 April, NRGI and IISD co-hosted the first in a series of webinars aiming to fill this gap. Three key lessons emerged:

- Political will is crucial. Governments must drive the energy transition. This is valid for both producer country governments, which should direct their NOCs in line with national strategic and political priorities, and wealthy consumer country governments, which must provide climate finance to enable developing and emerging producer countries to overcome the serious challenges of transition.

- Tunnel vision is deadly. NOCs can’t continue on the costly assumption the oil market won’t change. Climate advocates must increasingly consider the developmental challenges of producer countries and the needs, and potential roles, of NOCs.

- Economic diversification is key. Oil- and gas-producing countries have struggled with diversification for decades. Solving this is even more urgent now as producer countries must start actively investing in the long-term future. New producers should avoid making investments from the beginning that lock the country into a high-carbon pathway.

No more business as usual

Making incremental reductions in emissions compared to a business-as-usual baseline is no longer enough to mitigate the effects of climate change. This is because of the rapid and fundamental transformation in the way we produce and consume energy.

This change creates a challenge for companies whose core business is extraction of oil and gas, and especially for governments heavily dependent on revenues from NOCs.

Making incremental reductions in emissions is no longer enough to mitigate the effects of climate change.

These companies and governments should consider any new oil and gas investments in light of the significant uncertainty about future demand for their products and the economic returns they will generate, as well as their impact on climate change targets. Meanwhile, the status quo approach in many countries—whereby NOCs reinvest most of their oil revenues straight back into the sector—poses a growing risk to efforts to move away from fossil fuels.

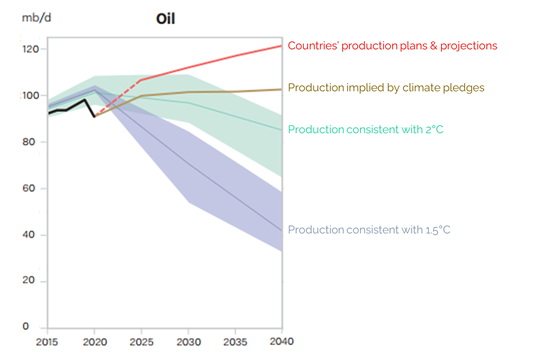

Global oil production would have to decline by 4 percent every year from 2020 to 2030 to be consistent with a 1.5°C pathway, according to the Production Gap Report. Yet current government plans and projections indicate an average 2 percent annual increase. This raises the question: what is the role for NOCs in a world of climate change adaptation and declining oil?

Source: The Production Gap

Experts weigh in

Executives from two NOCs, Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Uganda’s UNOC, joined our event to share their approaches to energy transition. Valérie Marcel of Chatham House, one of the world’s leading experts on NOCs, also contributed.

Juan Manuel Rojas shared Ecopetrol’s climate strategy, based on four pillars. While still focused on oil and gas, Ecopetrol aims to diversify its business into other sources of energy. The company bid for 51 percent of ISA, the state electricity grid operator. While many NOCs aim to reduce their direct operational emissions—so-called scopes 1 and 2—Ecopetrol’s energy transition strategy also targets scope 3, the indirect emissions that occur in its products’ value chain. The company aims to reduce emissions across scopes 1, 2 and 3 by 50% by 2050.

Asked to what extent these changes are driven by investors (88.5 percent of the company is state-owned and the rest is held by private investors), Rojas said often they are skeptical of the importance of an energy transition. From a financial perspective, many investors prefer their holdings to focus on one business area: if they want more electricity or more renewables, they would make those choices themselves. This creates a key tension in NOCs’ diversification efforts.

NOCs have two purposes: to deliver revenues to governments and to meet energy demand in their countries.

Peter Muliisa of UNOC shared Uganda’s challenges as new petroleum producer and a country with pressing socio-economic development needs. Like other countries in Africa, Uganda is highly vulnerable to climate change, and many officials and citizens see oil revenue as a means to help the country cope. However, with the global energy transition underway, UNOC has expressed a desire to develop a clear strategy on what the company needs to do to avoid exacerbating the effects of climate change on Uganda. Muliisa shared that, as a first step, early discussions are under way on how to restructure UNOC as an energy company rather than an oil company, ensuring Ugandans increasingly gain access to clean energy.

However, the government’s green light for construction of the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, which will carry Uganda’s oil to the Tanzanian coast, raises the question of potentially stranded assets. Muliisa explained that Ugandan officials hope to export oil through the pipeline before energy demand significantly shifts to renewables, but that the energy transition may affect longer-term production in the country.

Valérie Marcel, drawing also on the experience of these two companies, observed that NOCs have two purposes: to deliver revenues to governments and to meet energy demand in their countries (including often non-commercially). While clean energy is generally profitable, it does not create economic rents in the way oil does, which raises challenges for the countries’ economic strategies and government revenues. The second part of NOCs’ mandate could point to a role for NOCs in supplying renewable energy domestically. However, while NOCs can focus on reducing their costs or operational emissions, transitioning to renewable energy requires clear direction from their governments and consistent development strategies and climate policies, especially given the political consequences of lost economic rents.

Finally, Marcel said, the transition will affect different types of NOCs variously: high-cost versus low-cost, exporting versus importing, gas-focused versus oil-focused. Will it be easier for NOCs in new producing countries to transition than for established producers? In some ways yes, she said, as they are not yet locked into an oil development pathway. However, these producers often lack the financial resources needed for such a transition.

Our discussion series aims to increase learning between experts in the extractives governance and climate change fields, who have too often worked in silos. Our next event, on May 27, will explore whether NOCs should get directly involved in renewable energy investment and economic diversification.

Patrick Heller is an advisor at NRGI and a senior visiting fellow at the Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, University of California, Berkeley. Greg Muttitt is senior policy advisor for energy supply at IISD.