A Crash Course on Subsidy Definition by Dante, Shakespeare and Russian Folklore

Do you know what a subsidy is and what is not? If your answer is a definite “yes”, you are either new to the field or recklessly optimistic.

The devil, as always, is in the detail.

Here is an example. Despite undertaking the commitment to “phase out, over medium term, inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption” back in 2009, the G20 governments still have not agreed on what they mean by “inefficient”, “subsidies”, “wasteful”, or even “medium-term”. There have been of course a lot of suggestions for definitions of each of the elements, including by the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI). But the definition can only be useful if it is accepted by G20 governments. But consensus has so far been elusive.

This is not just an issue for governments – definitions vary even among expert organisations. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the International Energy Agency, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the GSI each have defined fossil-fuel subsidies in their own way – sometimes in total agreement or overlap with each other, but sometimes not. Each organization’s approach to defining subsidies is discussed in more detail in this executive primer.

The good news is that, of course, subsidies are not the only area where different actors cannot agree on a definition. And by now, humankind has accumulated plenty of wisdom that suggests reliable ways to overcome this limitation and advance the cause of “phasing out, over [blank], {blank] fossil-fuel [they that should not be named] that encourage [blank] consumption”.

The below crash course on subsidy definition is based on nothing less than the wisdoms of Dante Alighieri, Shakespeare and Russian folklore.

Dante’s Budget Inferno

Remember the devil in the detail? Steve Tidrick, a lawyer who served on former Vice-President Al Gore’s “reinventing government” project, in 1995 published an article titled “The Budget Inferno” in the New Republic magazine. Tidrick discussed the wasteful ways of US government spending and compared different types of subsidies to the Circles of Hell described in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

Tidrick’s powerful metaphor differentiates between subsidy types in terms of their varying degrees of negative impacts on social welfare. Similarly, other experts spoke of subsidies as “the good, the bad and the ugly”, including applying the same wording to environmentally harmful subsidies.

This gradation makes a point. Subsidies exist in many forms, and some of them are as ugly as hell. Lack of definition of harmful subsidies is not an excuse for inaction.

Shakespeare’s carte blanche for G20

If Dante Alighieri’s allegory made you sad and you feel that the state of play on fossil-fuel subsidies is tragic, think of Romeo and Juliet, “the saddest story in the world”. Remember what Juliet said? “What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”.

Even when there is no agreed definition of subsidies, parties at a decision-making table almost always intuitively understand what is, or is not, a subsidy. And if governments understand the need to move forward together, lack of definition will not be an obstacle to collaboration. This is exactly why last year the G20 set up a voluntary mechanism for peer review of fossil fuel subsidies. Under the peer-review, those governments that volunteer (to date the USA and China) can use the definitions that they see fit for the purpose and exchange lessons learned in general.

This way the G20 can still make progress against its commitment no matter what individual member countries have to say about definitions.

Russian nesting dolls

Advancing the reform under a voluntary peer review process within G20 as well as APEC needs less judgement and more trust as the GSI has already argued in an earlier policy brief. Some have explained subsidies through concentric circles. One excellent example was published by OECD in 2010 and can be found on page 7.

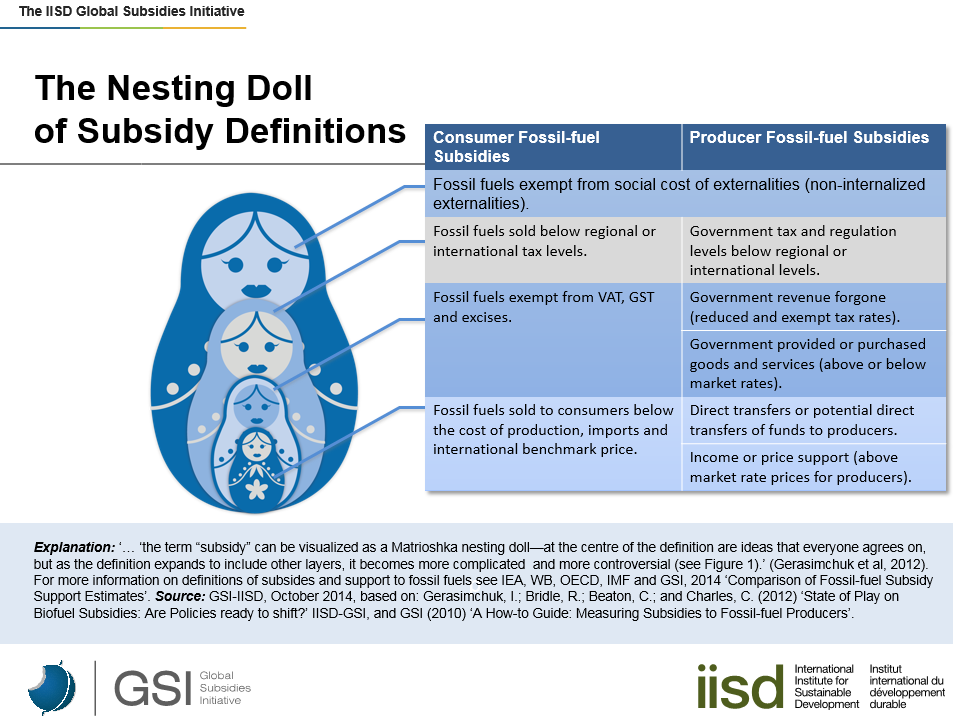

At the GSI we have seen that the more agreement there is about the most straightforward types of subsidies and their negative effects, the more likely decision makers concerned are interested in working to reform them. Therefore we at the GSI tend to visualize the definition of a fossil-fuel subsidy as a Matrioshka nesting doll—at the centre of the definition are ideas that everyone agrees on, but as the definition expands to include other layers, it becomes more complicated and more controversial. The figure below illustrates this idea in detail.

At the center of the definition are direct transfers from government budgets to producers and consumers of fossil fuels. In case of consumer subsidies, it is also not uncommon for governments to push the cost of subsidies to state-owned companies that sell fuel at below market rates or at a loss; this is still a transfer of funds. If this type of government support to consumers is not targeted to the poorest groups only, it often represents a heavy burden on government budgets. This is the smallest of the nesting dolls, but it is not small at all in countries like Indonesia and Bangladesh!

The second biggest Matrioshka encompasses all government revenue forgone in terms of uncollected or uncollected levies on extracted fossil fuels and fossil fuels sold to consumers. In other words, the value of this support equals the deviations from the national benchmarks of the respective corporate profit taxes, property and land taxes, royalties, fees on infrastructure use for producers, and breaks on VAT, GST and excise taxes on fuel sold to consumers.

These two inside nesting dolls are the ones where many countries have undertaken reform efforts recently and where G20 and APEC commitments concentrate as well.

The third nesting doll takes a step further. Each country has its own national tax benchmarks. International organisations such as IEA and IMF have come up with certain regional and global benchmarks, in particular, for fossil-fuel consumer taxes. This raises the question whether it is more appropriate to calculate deviations from these international benchmarks rather than nationally-established levels. This third Matrioshka is of interest to decision-makers concerned about international competitiveness and trade, especially for fuel-intensive industries.

Finally, the outside Matrioshka is about non-internalised externalities; first of all, negative impacts of climate change. Whether or not this constitutes a subsidy is subject to a lot of debate. For instance, the IMF argues that it is a subsidy, and it is the inclusion of this nesting doll that explains why the IMF consumer post-tax subsidy estimate of USD 2 trillion in 2012 is so much higher than IEA’s estimate of USD 544 billon in the same year.

The nesting doll approach to subsidy definitions is not dogmatic. After all, Matrioshka is a toy for children, but it is an educational toy. Governments, experts, civil society and businesses are all learning how to assemble different reform pieces together – into something sustainable and positive, just like Matrioshka.