How Electricity Subsidy Reform Can Benefit Indonesia

The Government of Indonesia has been considering a new wave of electricity subsidy reforms since January 2016—delaying its plans twice now for a combination of political and practical reasons. Almost every time and in every country, citizens do not welcome such reforms, asking questions like "Will I have to pay more for power?" "Why do prices need to go up anyway?" and "How are the poorest expected to cope?" But while costs and risks are often well understood, the benefits and opportunities of reform do not receive the same attention. There is a lot that Indonesia could gain from rationalizing its subsidies—as long as reform is implemented sustainably. Energy policy can do a better job at promoting social equity, and the money wasted on subsidies can be reinvested in people and the health of the economy. In particular, one focus for reinvestment should be the production of clean energy.

What is the situation in Indonesia anyway?

See 10 Things You Need to Know About Electricity Subsidies in Indonesia.

Fairness in all things—including energy policy

Generally, people agree that the poorest in Indonesia should benefit the most from subsidies. But data shows that the electricity subsidy is not fairly distributed: around 45 million households—over 70 per cent of the population—benefit from subsidized electricity. Better-off households have more money so they can buy more electricity. As a result, the bulk of subsidy benefits end up in their pockets. The very poorest may not be able to access or afford electricity at all, in some cases receiving no benefits. Millions of poor households are thought to be in this situation.

The main aim of electricity subsidy reforms, as described by the government, is to attempt to concentrate the subsidy on the poorest 40 per cent of households. Broadly speaking, this includes the “poor”—those living below the poverty line—and the “near poor”—those most vulnerable to falling into poverty as a result of changing circumstances. If reform is well implemented, better targeting of subsidies to poor households should do a better job of using Indonesia’s resources for the greatest benefit to its people.

Electricity subsidy reform is in fact a continuation of policy reforms that began in 2013, when the government made its first significant move to curb the ballooning electricity subsidy bill by increasing tariffs for a number of users and excluding government, business and large residential consumers from subsidies.

Better quality spending—subsidy reallocation

Indonesia’s electricity subsidy is currently the most expensive energy subsidy on the national budget—and it can only be expected to get bigger. Over the past 10 years, largely due to growing demand and currency devaluation, electricity subsidies have increased from IDR 8.8 trillion in 2005 to IDR 57.6 trillion in 2010 and IDR 101.82 trillion in 2014 (from USD 1.4 billion to USD 6.3 billion to USD 8.57 billion). Spending has dipped recently, with IDR 50 trillion (USD 3.8 billion) allocated in 2016, but this can be expected to grow again unless steps are taken to further reduce coverage.

This is an enormous share of state resources—in 2014, equal to almost 5 per cent of all state expenditure; in 2016, almost 2.5 per cent. If the existing policy is inefficient, one of the key arguments for reform must be that savings could be spent better.

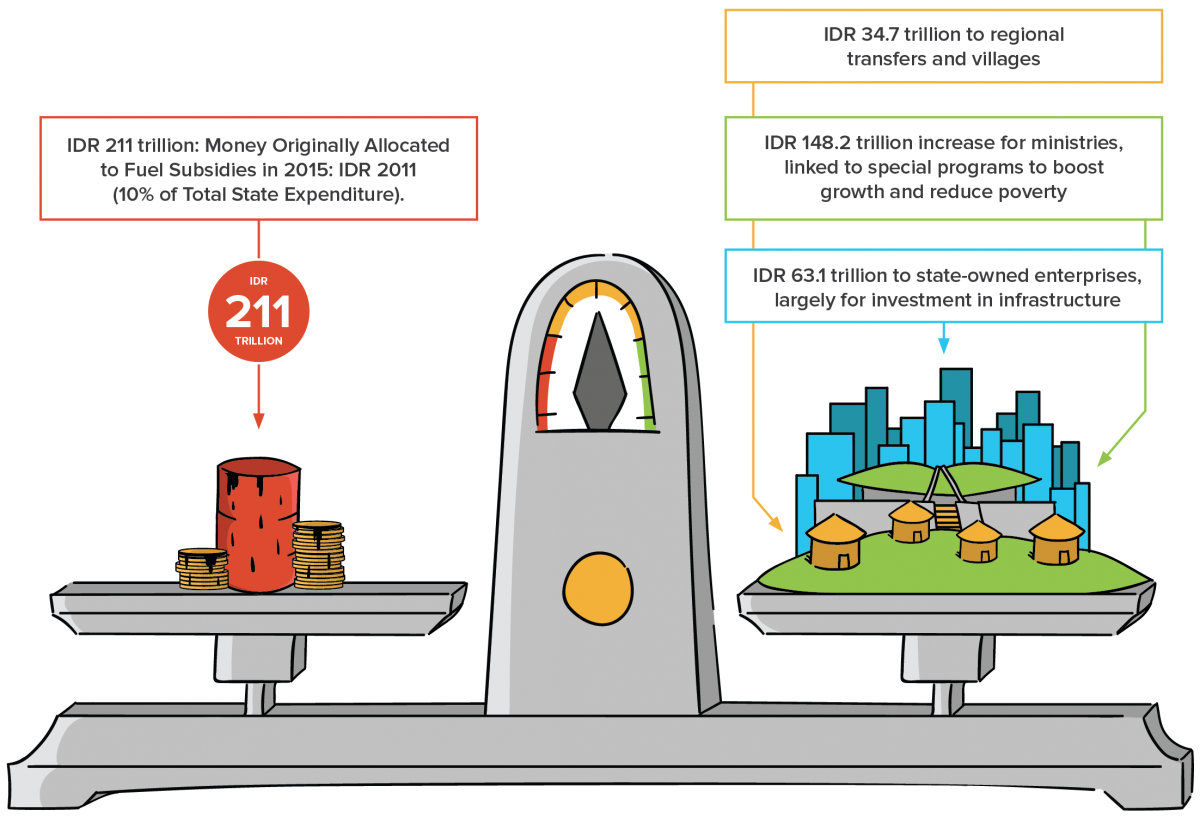

In early 2015, the reform of gasoline and diesel subsidies allowed for large increase in the budget of ministries linked to a number of special programs focused on poverty reduction, as well as a capital injection to state-owned enterprises and helping to fund an increase in the transfer to regions and villages. The shift in resources was not without criticism—but a series of interviews with civil society organizations that specialize in budgetary analysis found almost unanimous agreement that it was an improvement on the previous subsidies.

A fossil fuel subsidy swap: invest in clean energy instead

Coal currently covers around 50 per cent Indonesia’s electricity capacity and major expansions in domestic coal-generated electricity capacity are planned. Coal is a dirty fuel, responsible for local air pollution that will lead to thousands of early deaths and impaired lives through respiratory disease; as well as causing global air pollution—greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—which may have drastic implications for Indonesia as an archipelagic nation. By 2035, the electricity sector is expected to be one of the largest sources of GHG emissions in the country.

By selling cheap electricity to 45.1 million consumers, Indonesia is indirectly subsidizing fossil fuel-generated electricity consumption through its tariff system. Based on the assumption that subsidies are equally shared across all types of power generation, we could estimate that around IDR 101.91 trillion (USD 4 billion) was spent subsidizing coal-fired electricity in 2014, compared to only IDR 12.2 trillion (USD 1 billion) for power derived from renewable technologies.

The savings from electricity subsidy reform are an opportunity to invest in the future of Indonesia’s energy mix by backing a greater share of renewable energy. This would see savings continue to be used in a way that would benefit all Indonesians. Other countries, including China, have already moved in this direction, because the use of coal comes with considerable external costs that are not included in current price comparisons. Renewable energy also improves energy security because it is domestically produced and clean on both local and global levels.

The reinvestment of subsidy savings in renewable energy did not take place when gasoline and diesel subsidies were removed in 2015—there is a compelling argument for this not to be overlooked again.

Demanding better quality of spending—and watching implementation closely

Despite its essential political unpopularity, the motivations behind Indonesia’s electricity subsidy reform plans are noble. Reform is an opportunity to spend government resources more fairly to help the country’s most vulnerable households. It is also an opportunity to free up investment in people and the economy.

Of course, much depends on implementation. The task of targeted electricity subsidies to only the poorest is complex and will create challenges of exclusion and inclusion. It requires good preparation and ongoing monitoring and adaptation, including mechanisms to listen and respond to grievances from consumers. There is an important role to be played by civil society organizations to hold government to account and seek the best deal for Indonesian citizens. Similarly, the reinvestment of subsidy savings, which will largely be devolved to budgetary negotiation among parliamentarians, may not take full advantage of the potential to back greater levels of investment in renewable energy, unless citizens make clear demands to their public representatives.

Electricity subsidy reform is an opportunity—but only if the right forces come together to make the most of it.

The Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) runs a program of work on fossil fuel subsidy reform in Indonesia, having conducted a significant body of technical analysis since 2010 to support government ministries and non-government stakeholders in understanding and preparing for reforms. It remains committed to supporting Indonesia to implement fossil fuel subsidy reform with well-timed analytical support and policy advice. For more information, please contact ltchristensen@iisd.org.